Toshiko Mori abides by no style. Modernity is elastic. The former of Harvard’s graduate architecture program looks the load bearing structure of buildings to excavate material matter—revealing the complexities and contradictions of modern human phenomena.

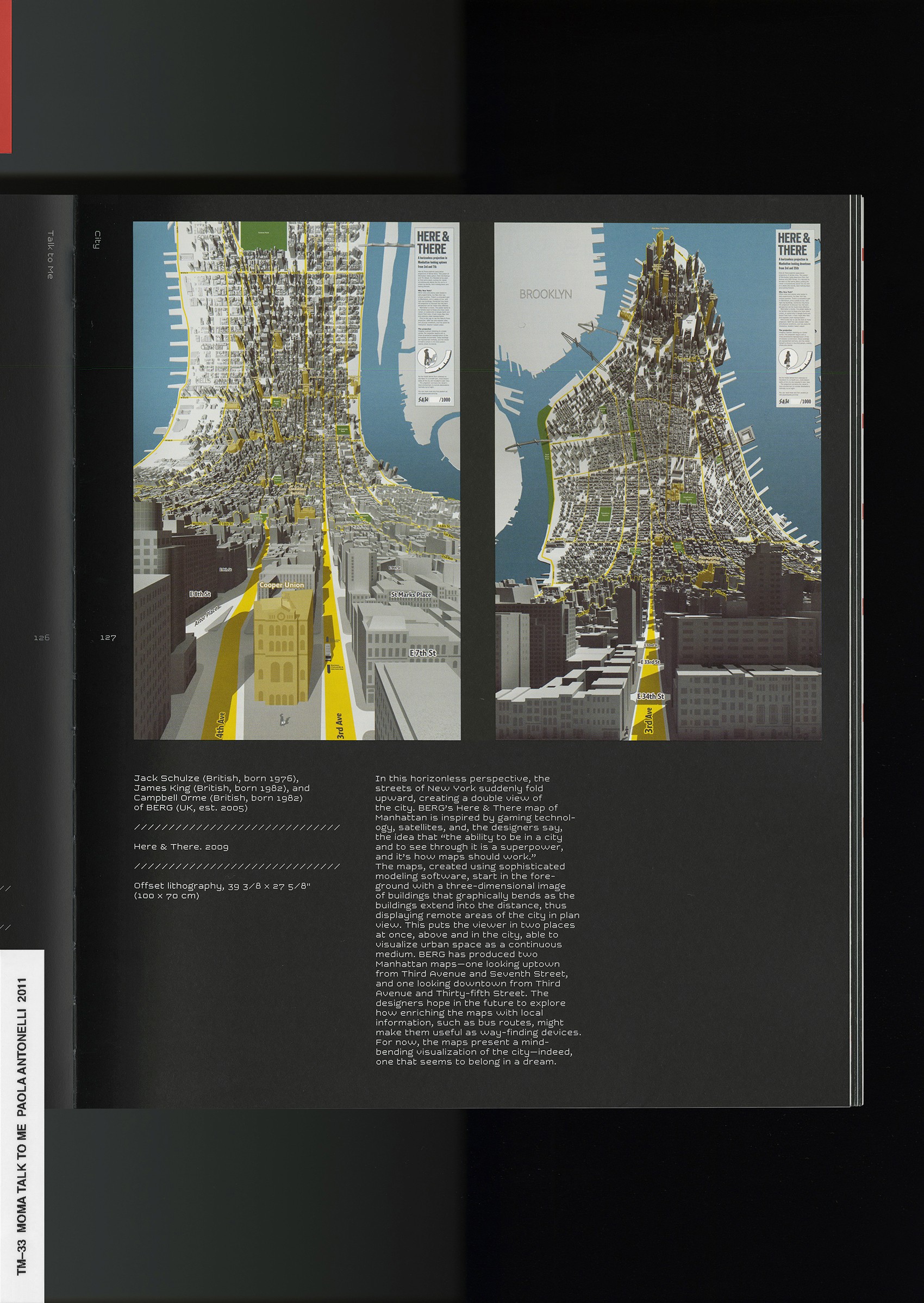

NR

Many urbanists say that public life in the eighteenth century—which is when the began to take shape—was formulated by and for men. What do you think modern cities would look like today if they were built by females at their origin?

TM

It's an interesting idea that there's a gendered attitude towards cities. , a feminist scholar, compares as a city built by men to as a city built by women—both in terms of mythical existences. There's the [female] presence of the Amazon and then there's the island of , an entire civilization built by women. And also there's Athens, Greece where many goddesses were revered and rural women in the Greek republic were very very strong as rulers. There’s a lot of reference to Rome as being more male centered—interested in power and politics. This idea of cities built to fortify themselves and to fight the enemies is a bit more male-centered. So, there is this mythical idea of cities built by men or built by women. Those myths are very powerful in the psyche.

So, the bottom line—cities built by women—involves the concept of soft borders for all sorts of situations. Meaning, instead of defense, there’s going to be a blurring of enemies and in terms of the class system. Instead of having a very segregated society spatially and hierarchically, there is a blending of many class systems with constant supporters enabling anybody to cross a border to another area to empower them.

Stereotypically, the element is nurturing. In my mind, the most powerful book about this is by Suzanne Simard, Finding the Mother Tree01. The book is an incredible metaphor for the forest as a city. The mother tree really helps grow not only its own species but others as well. It makes a root system which is sustainable, empowering both the and to help mushrooms and ferns create a more inclusive environment for the growth, longevity, and survival of the forest. As you can see, the forest has survived longer than any civilization. To me, through looking at the biological and natural resource origins, I think that Finding the Mother Tree is probably the best metaphor for thinking about what a city would look like if a woman were to build it.

NR

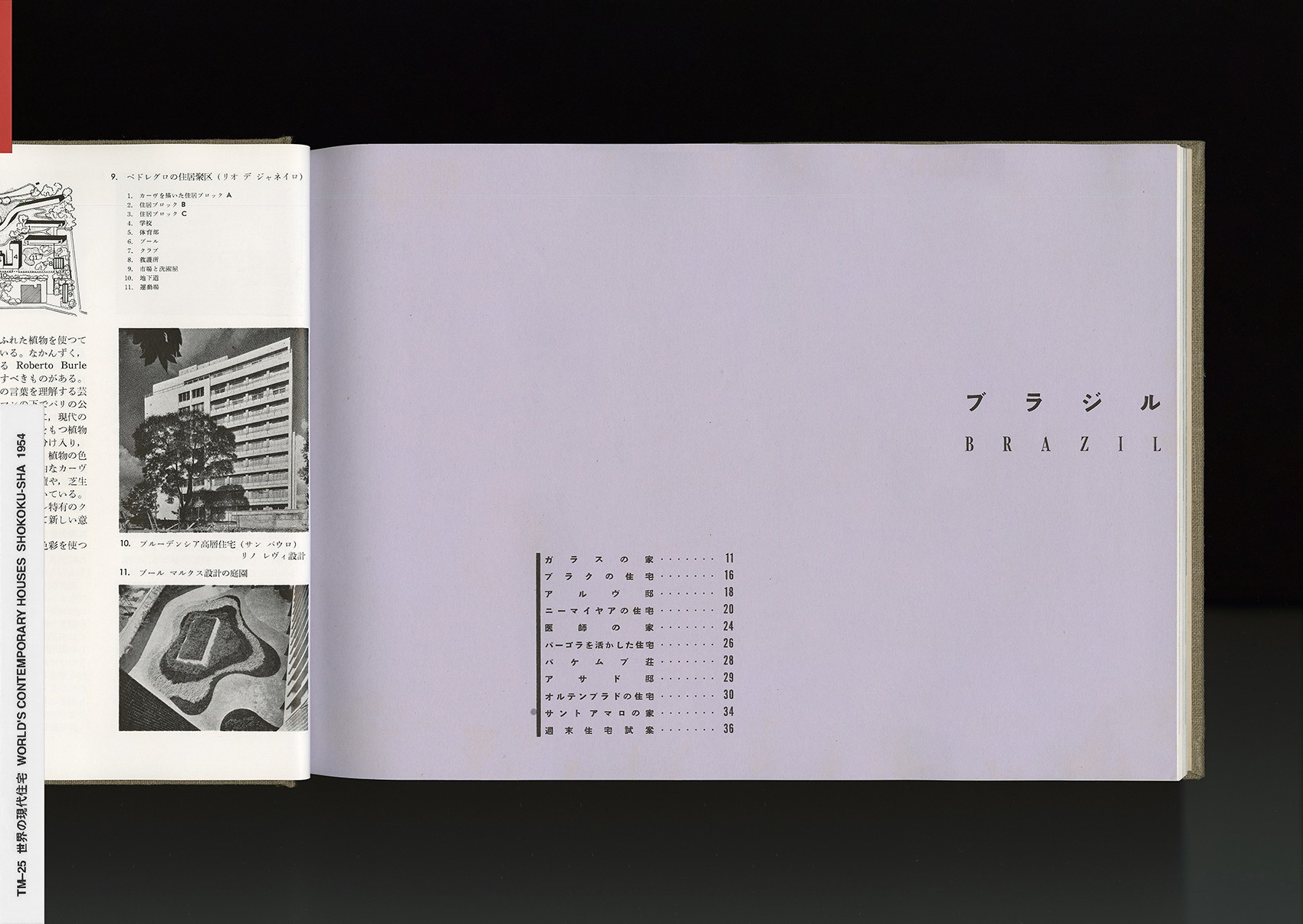

In your library, what obsessions or longstanding collections have been important to the development of your work?

TM

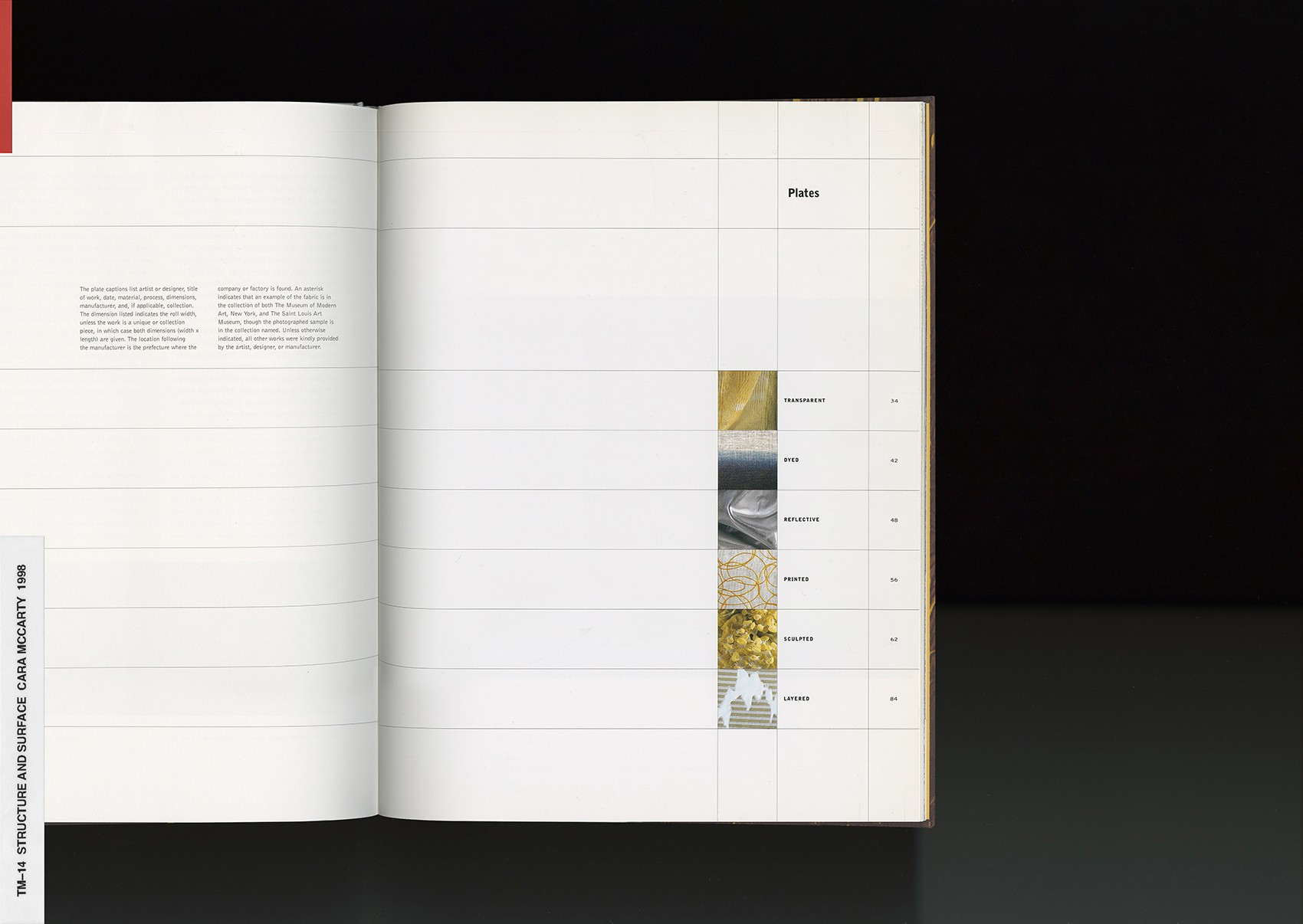

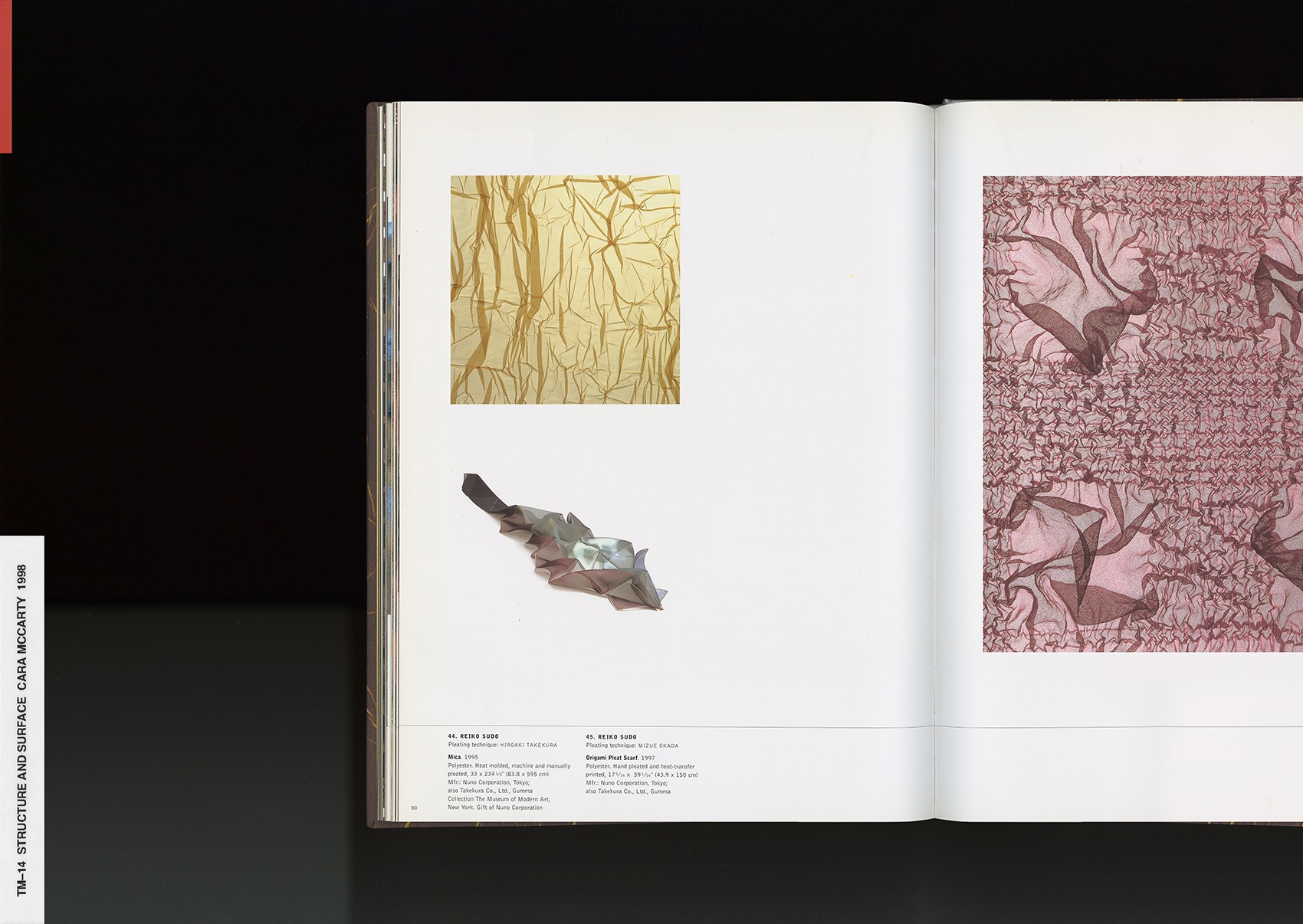

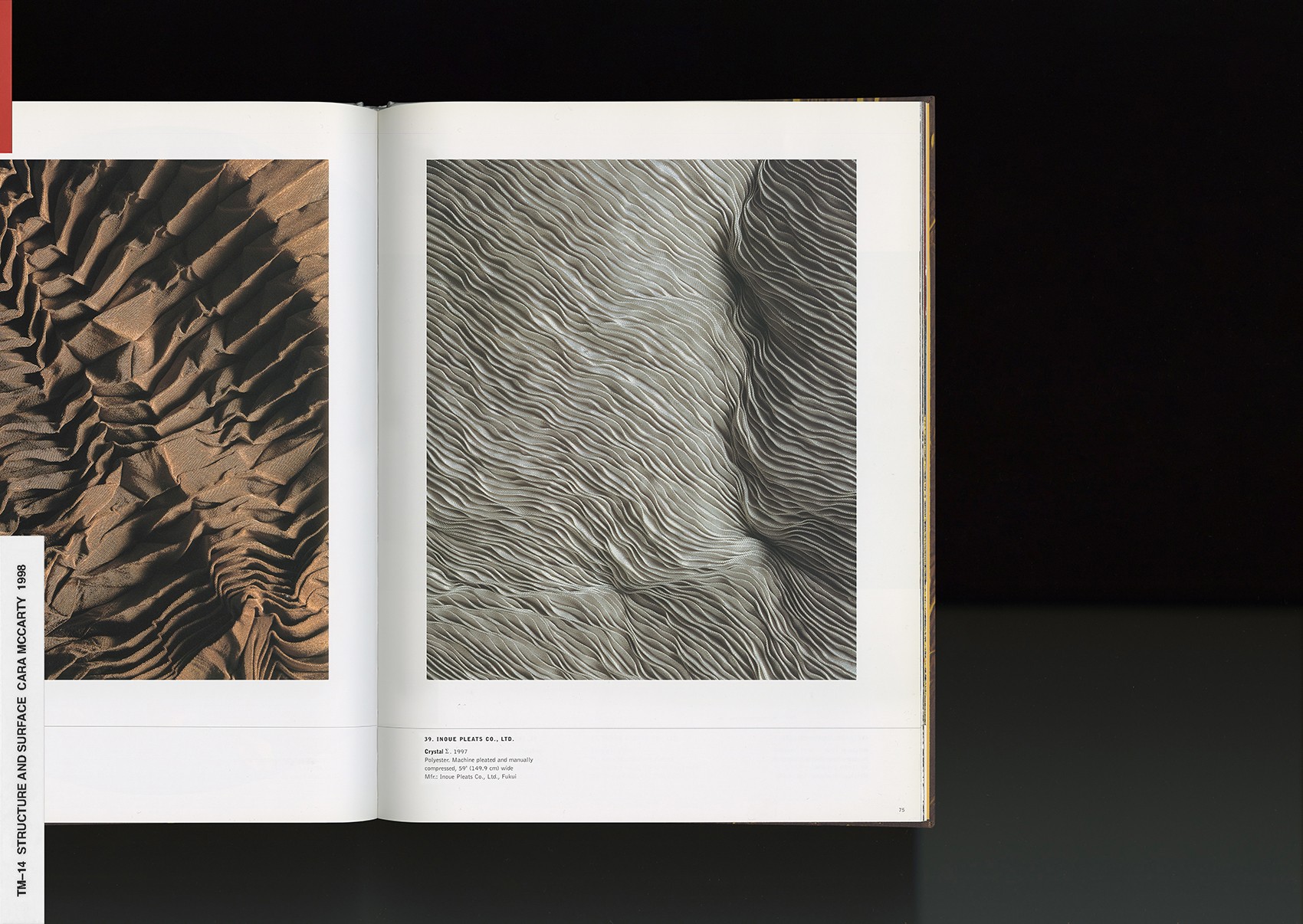

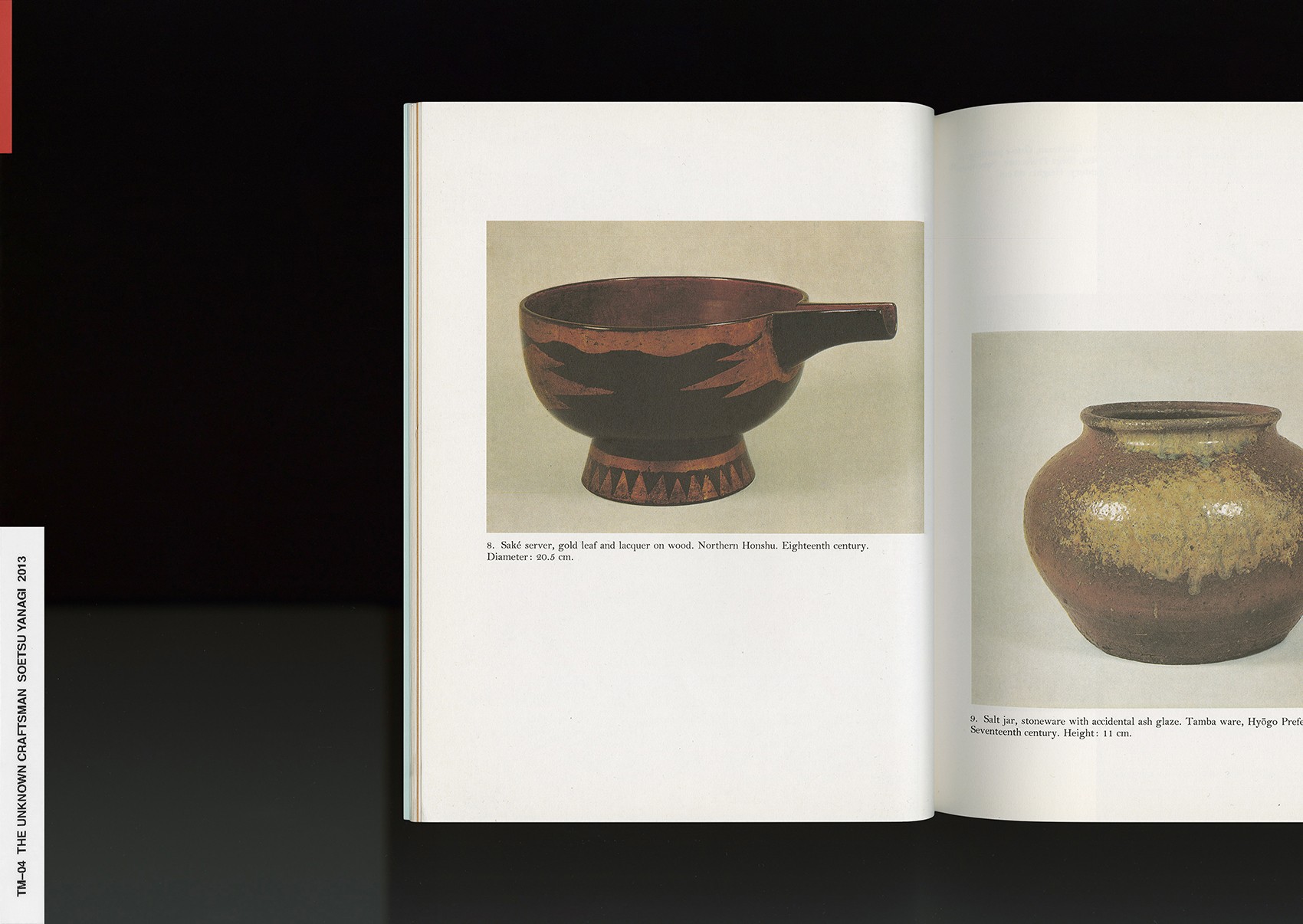

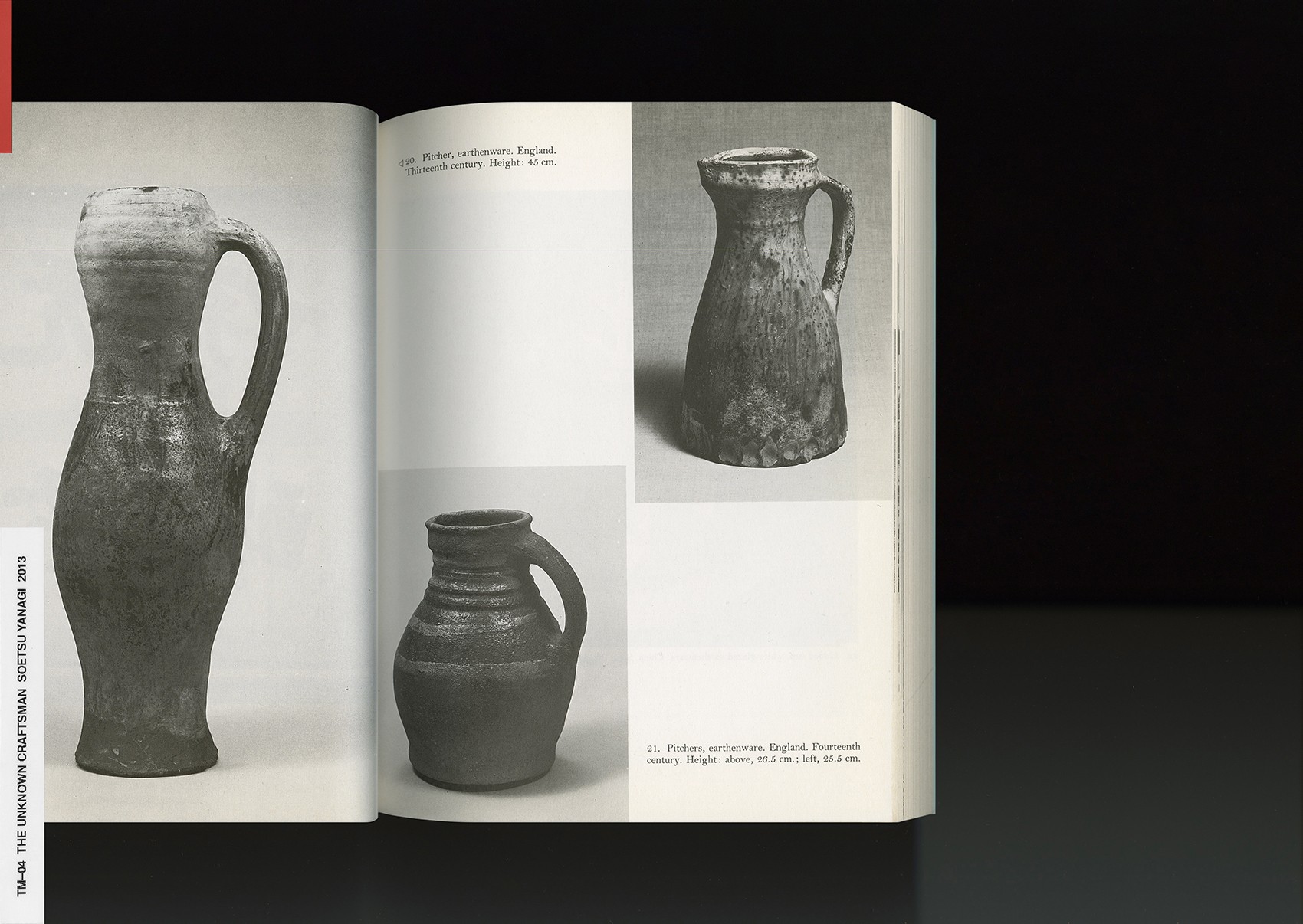

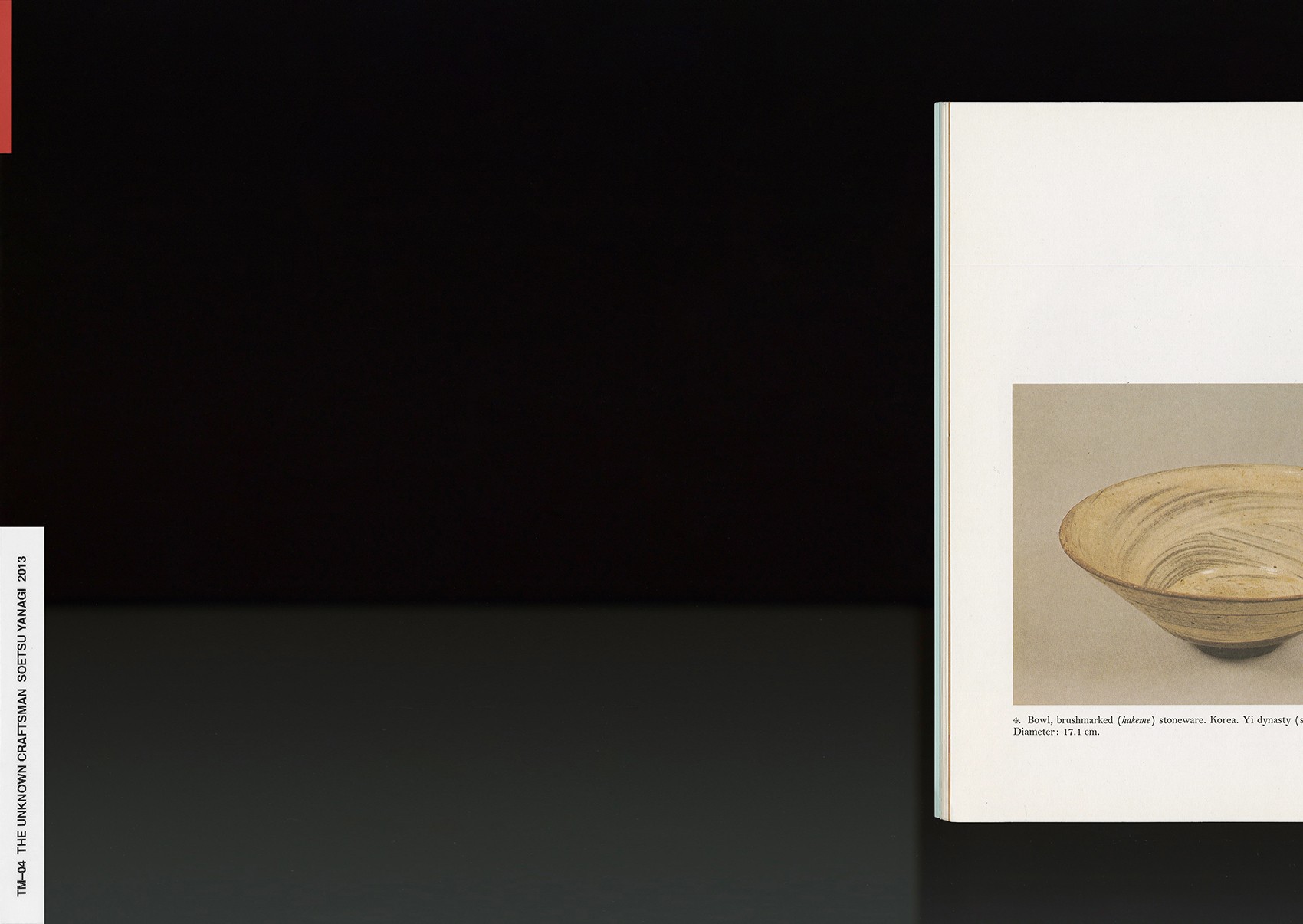

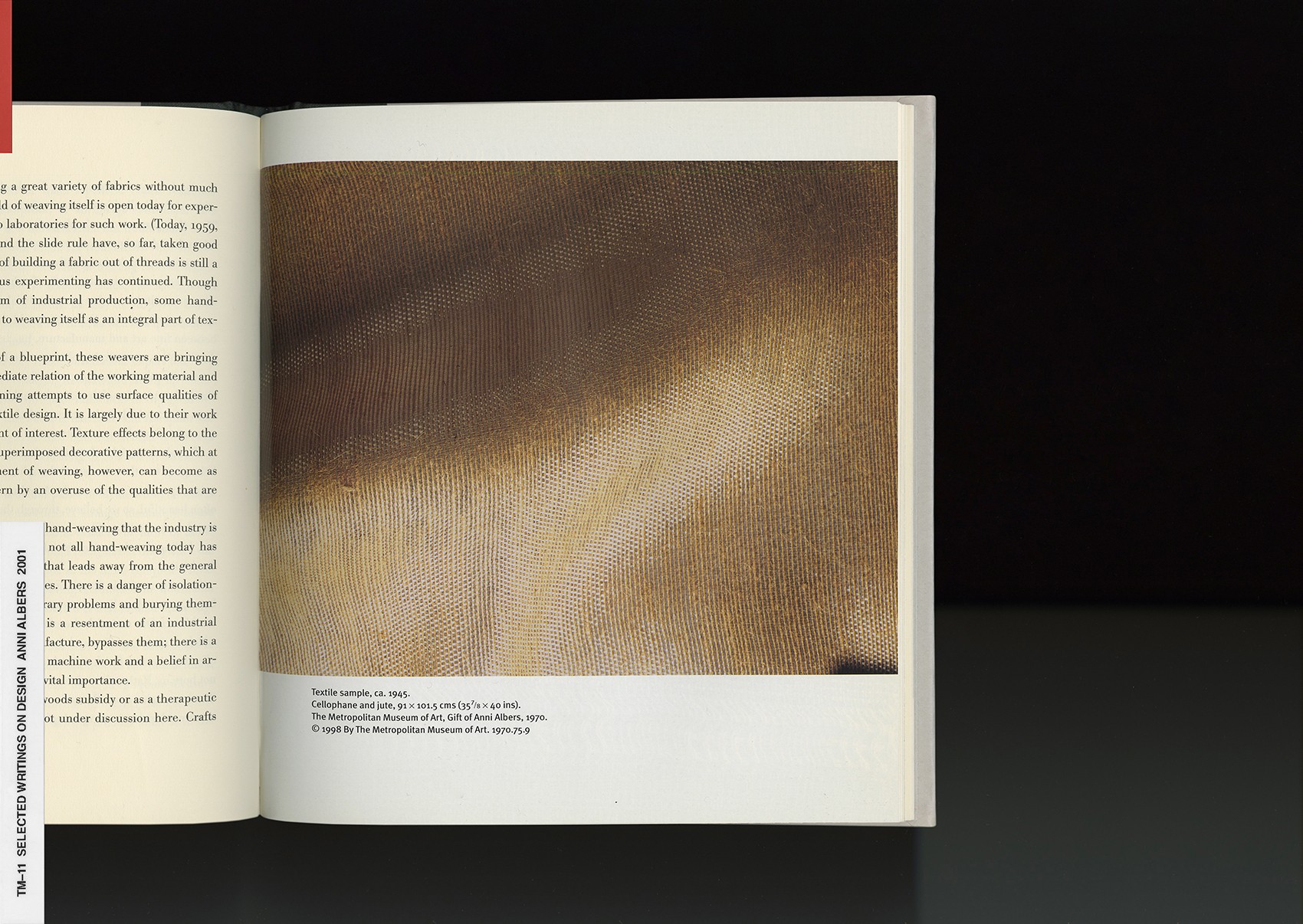

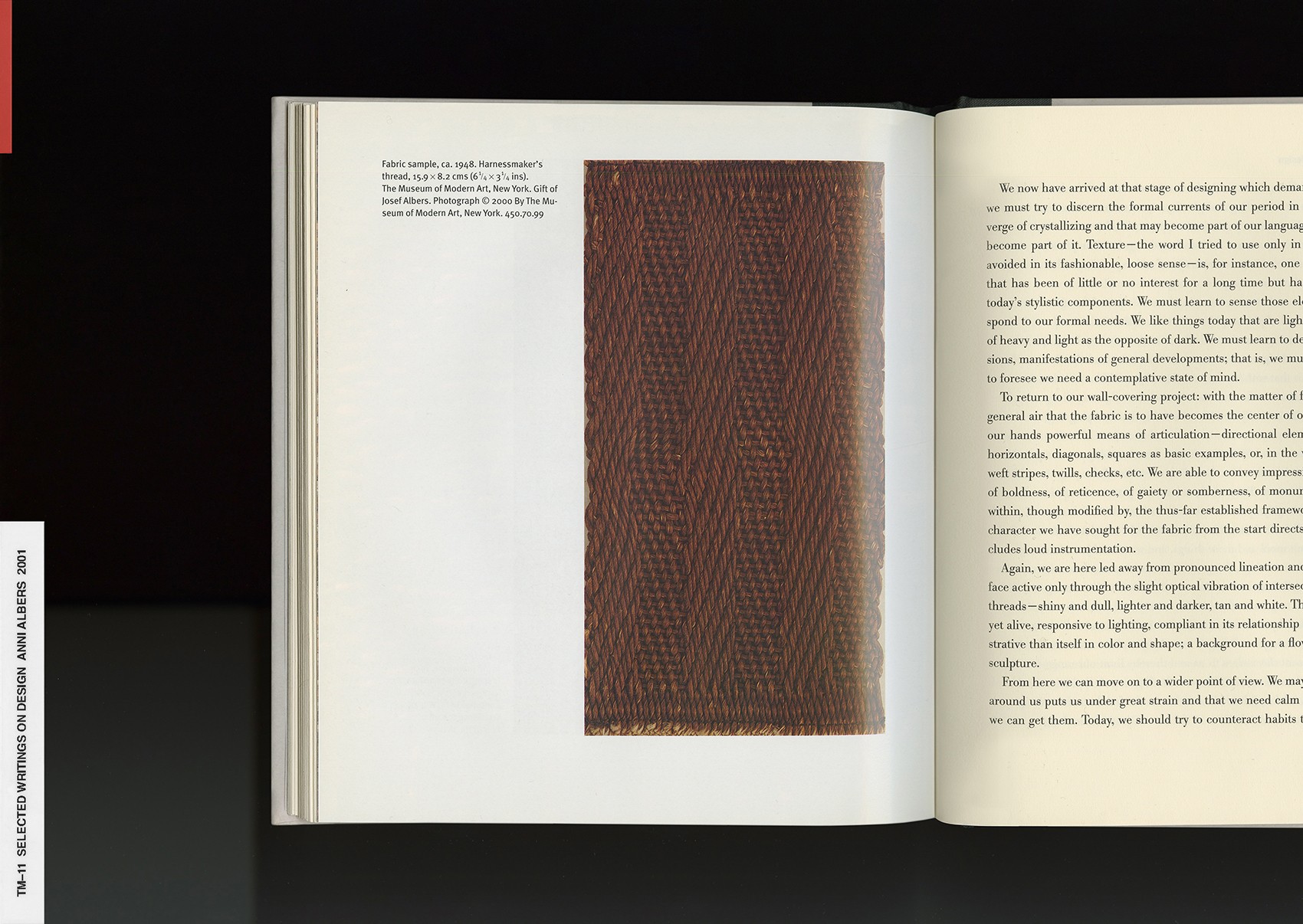

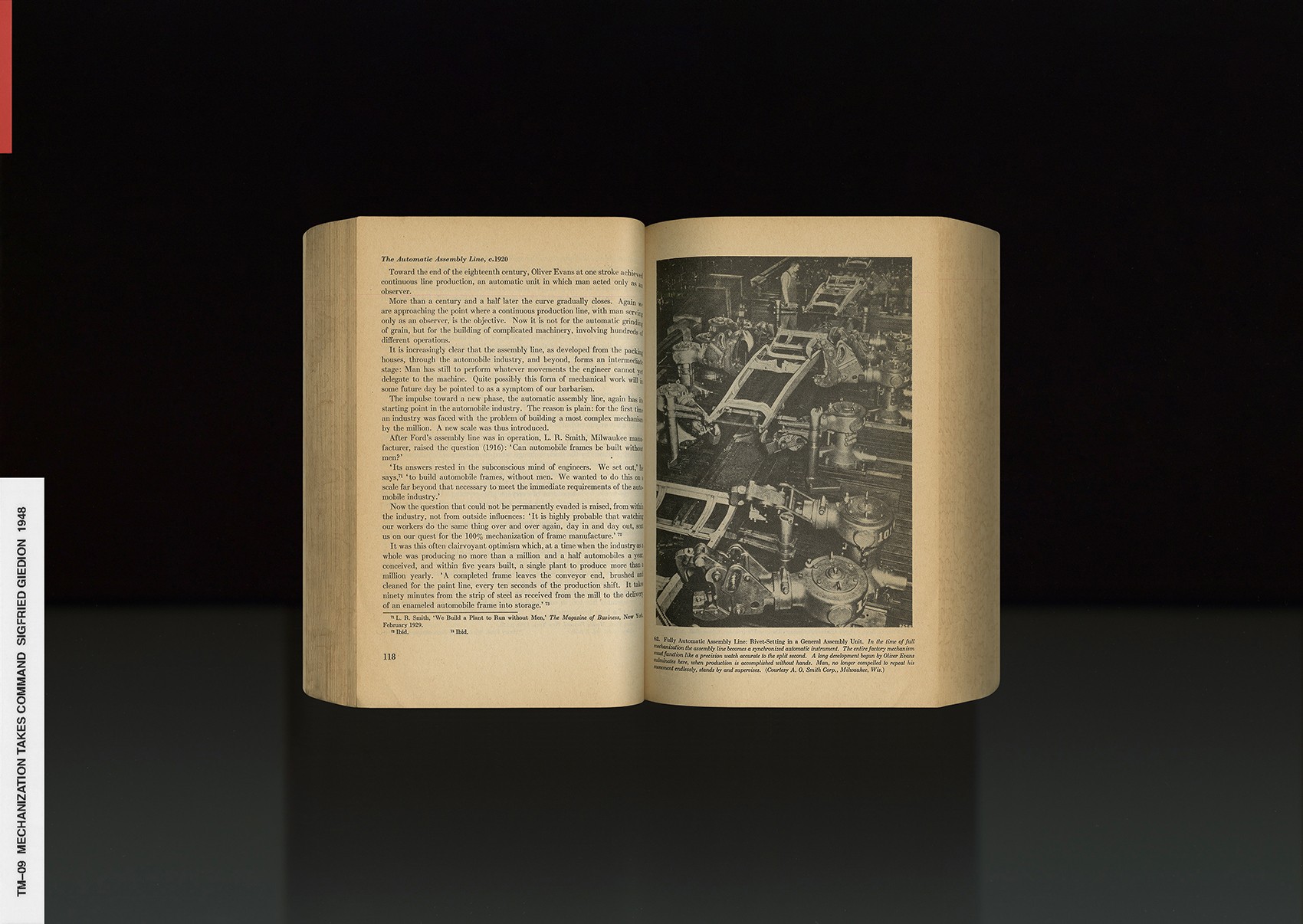

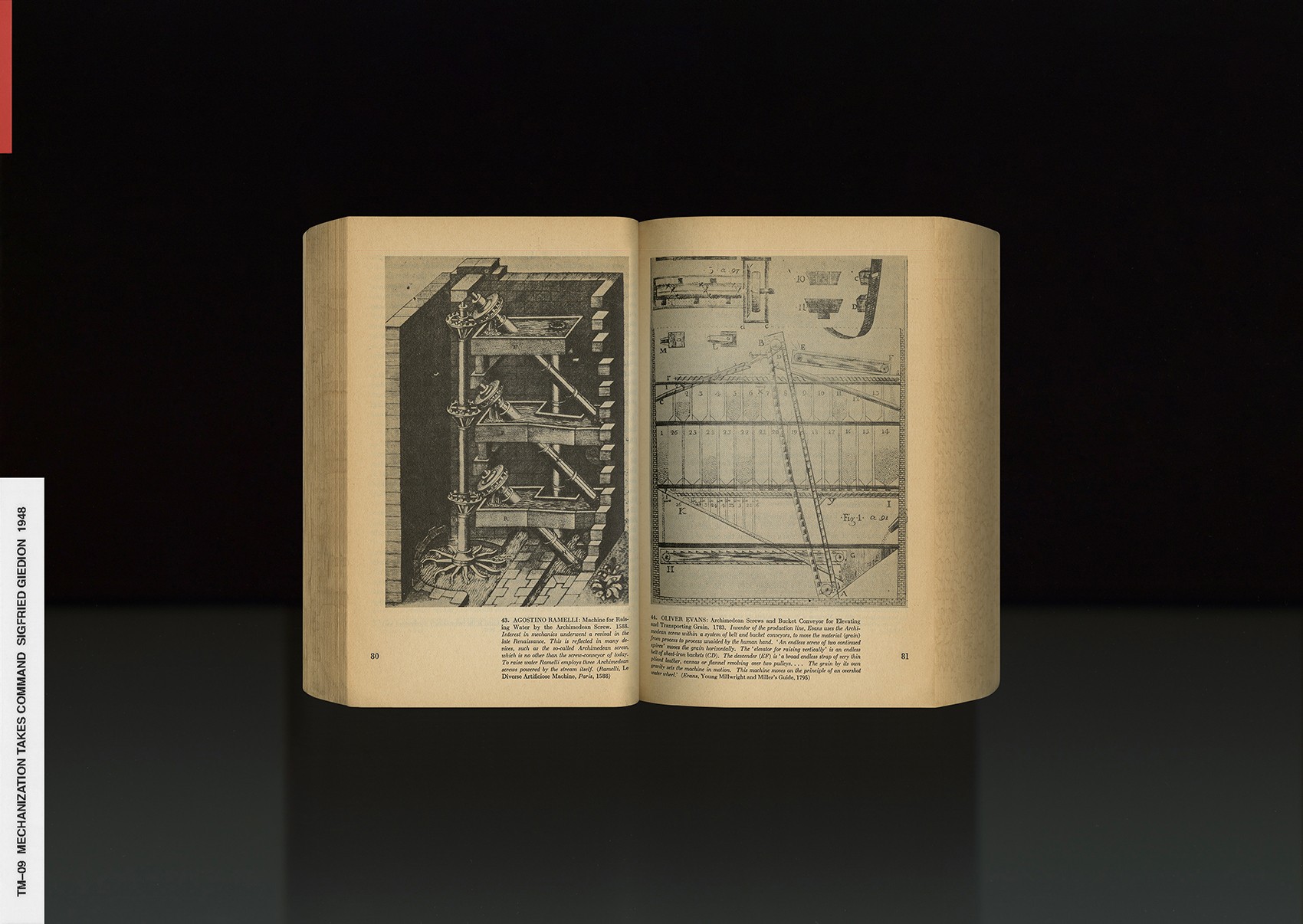

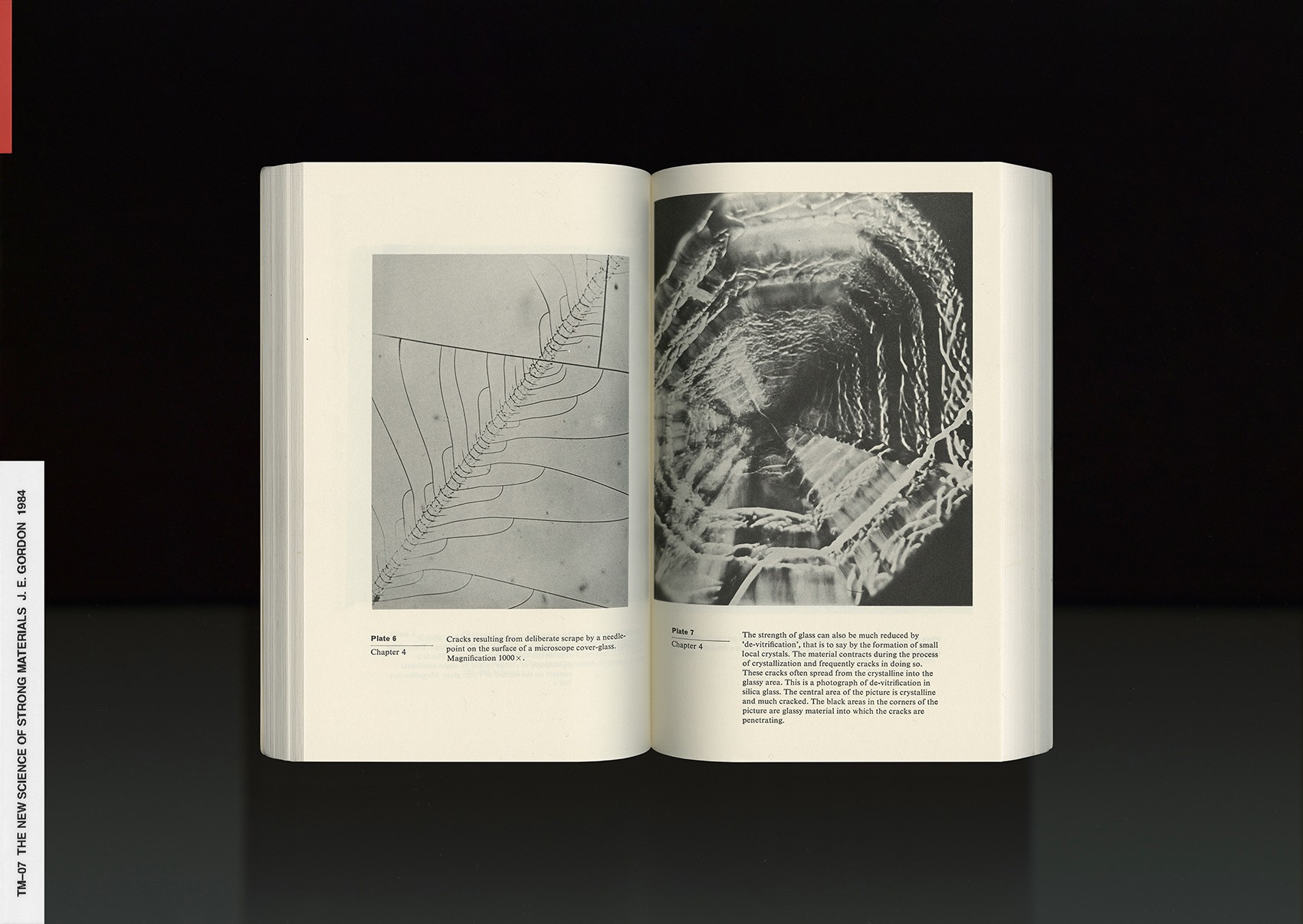

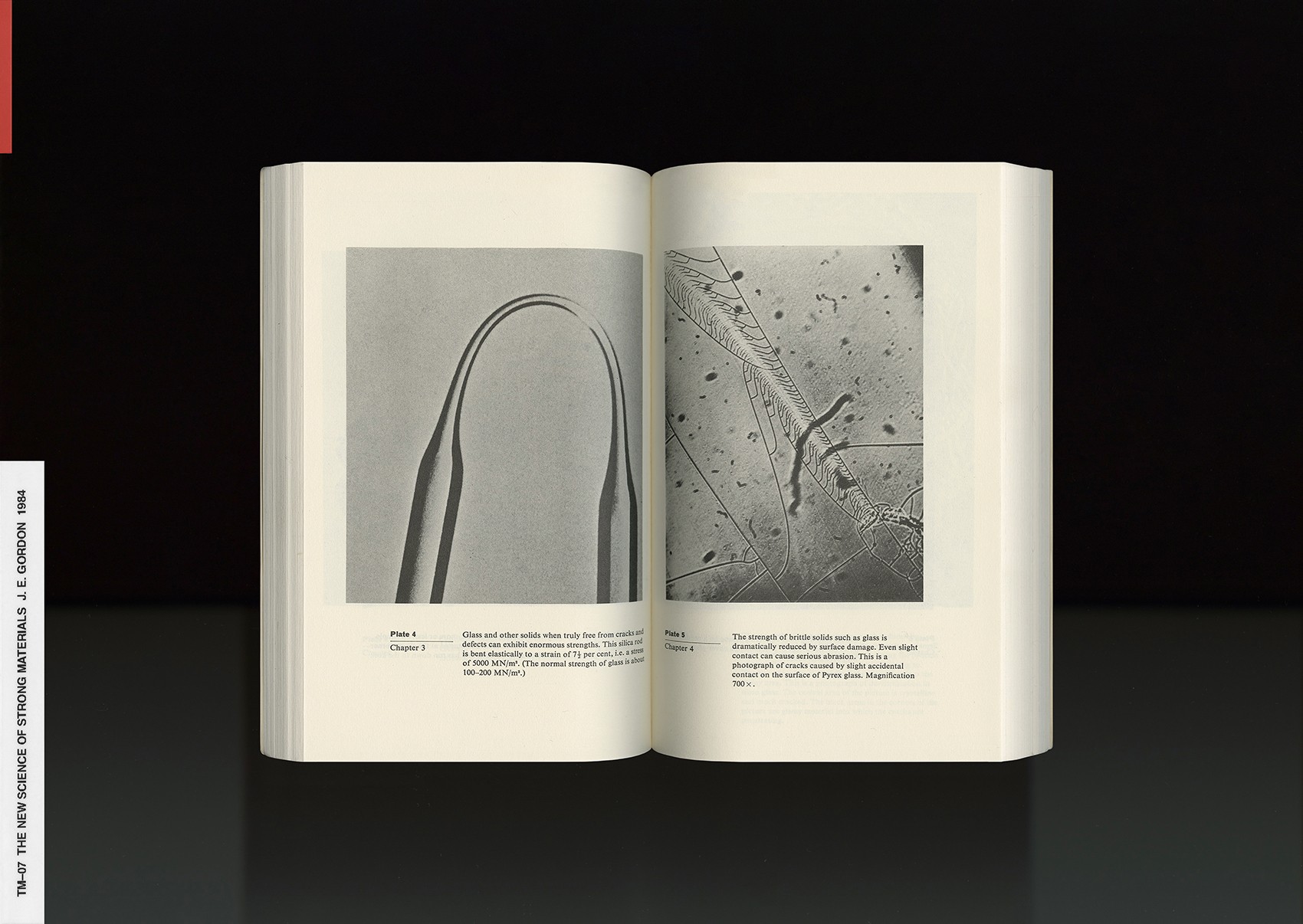

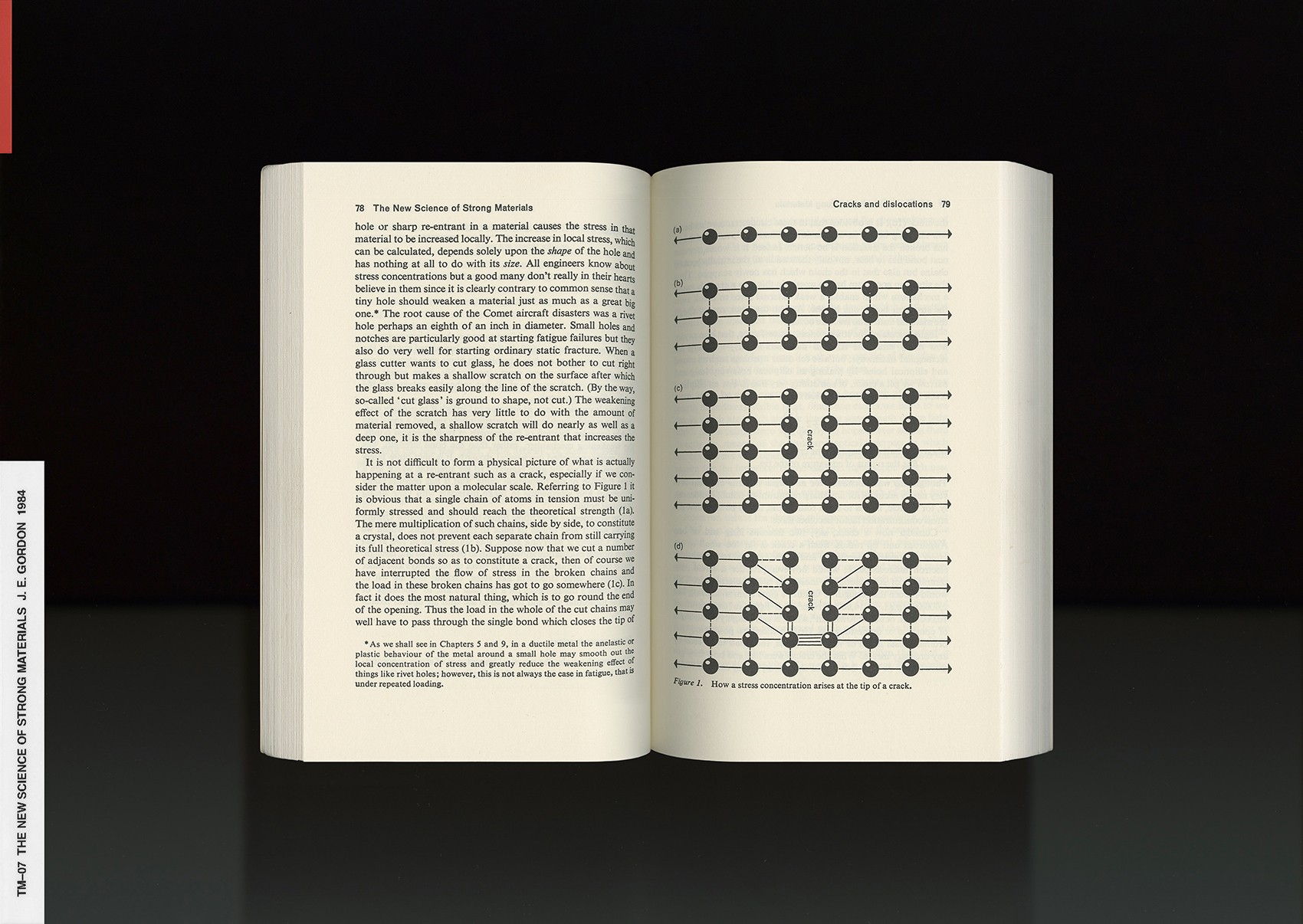

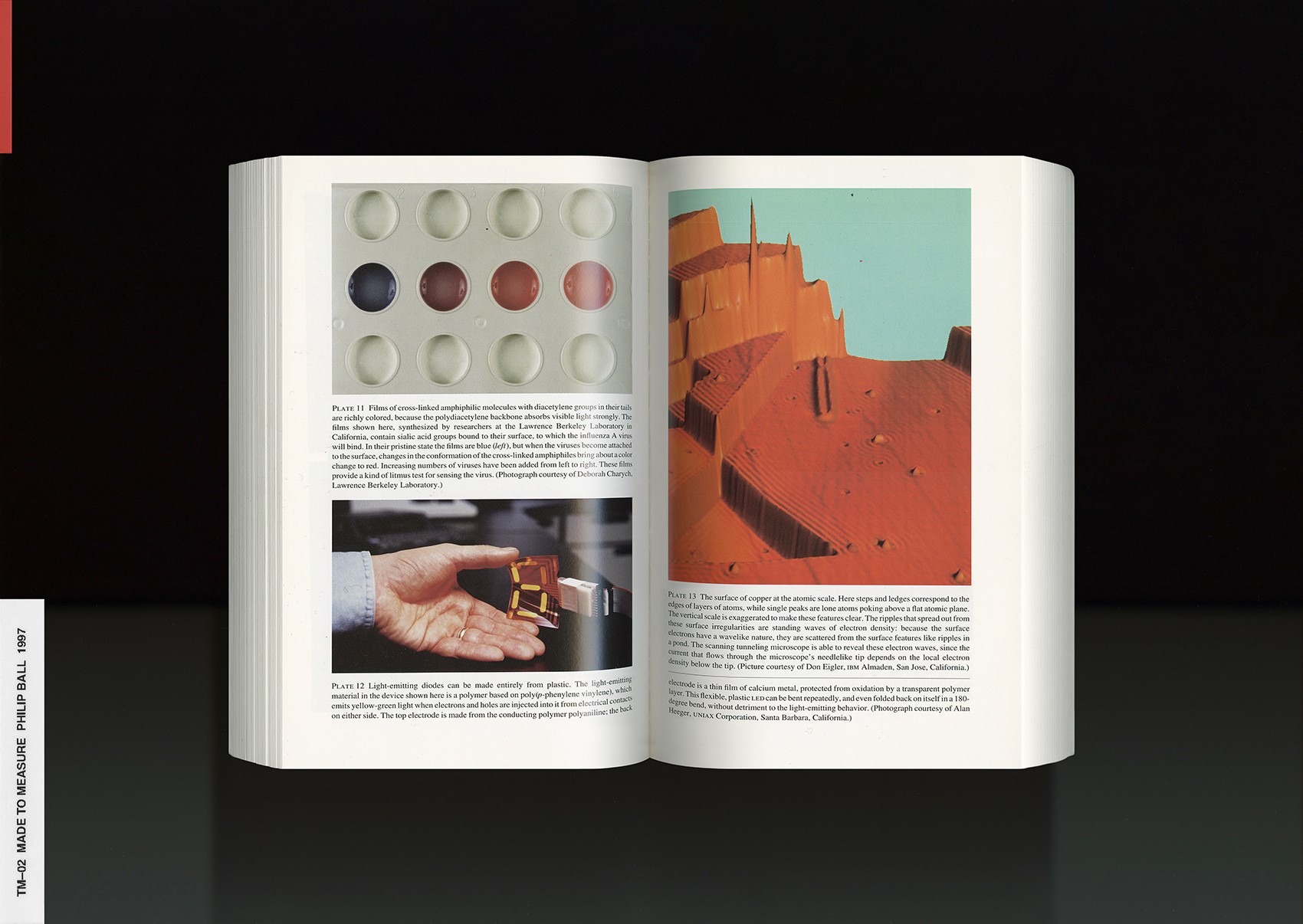

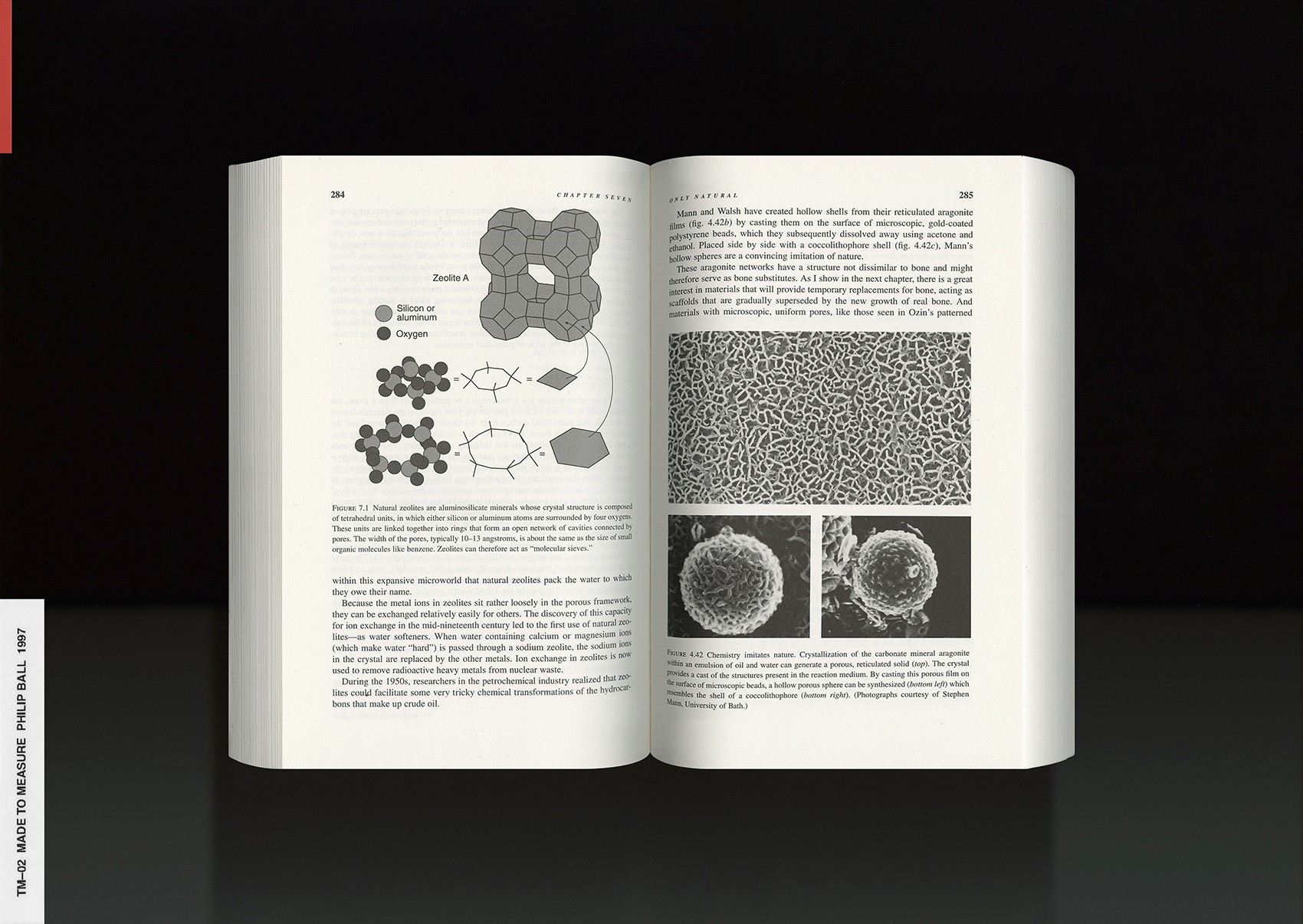

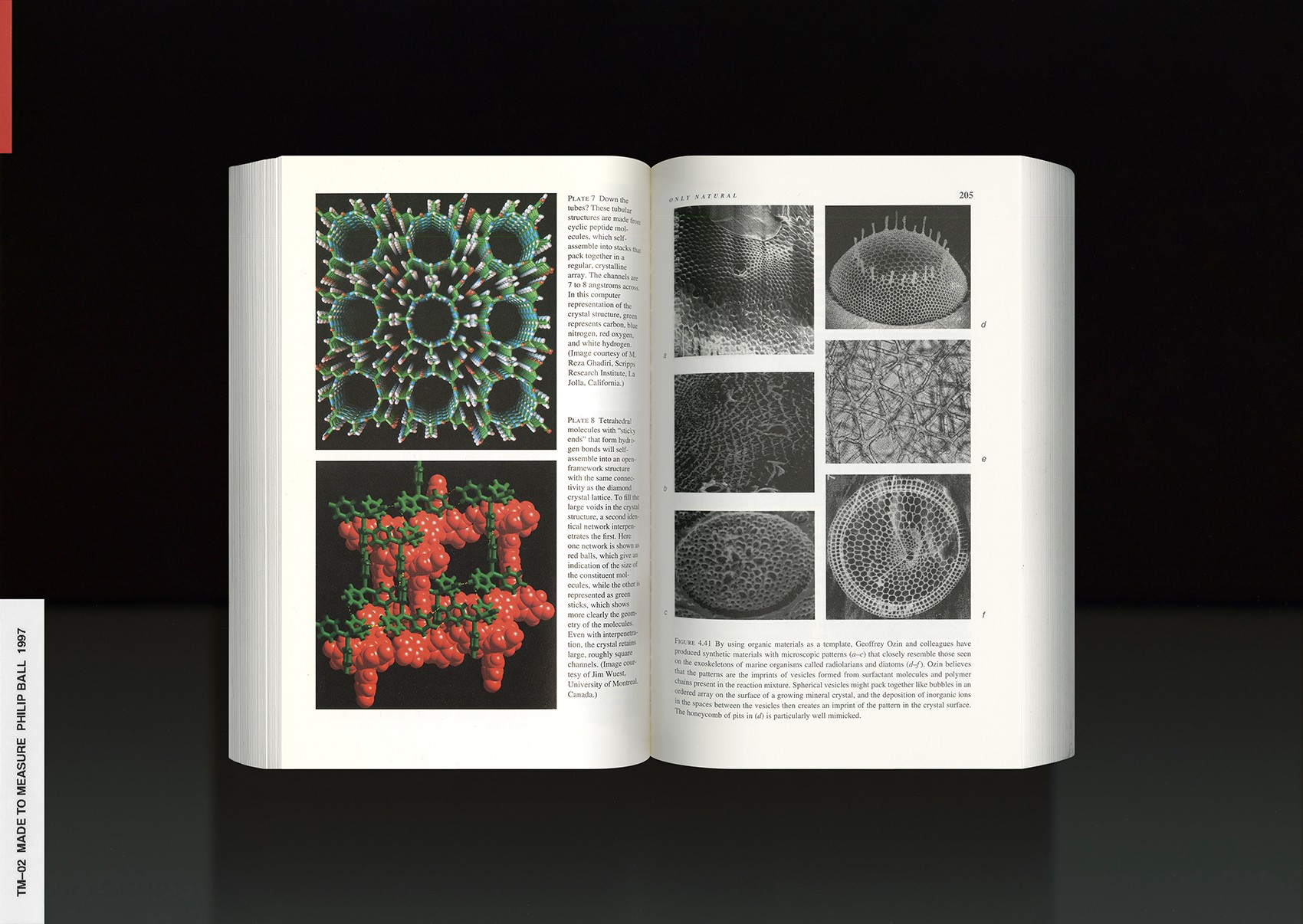

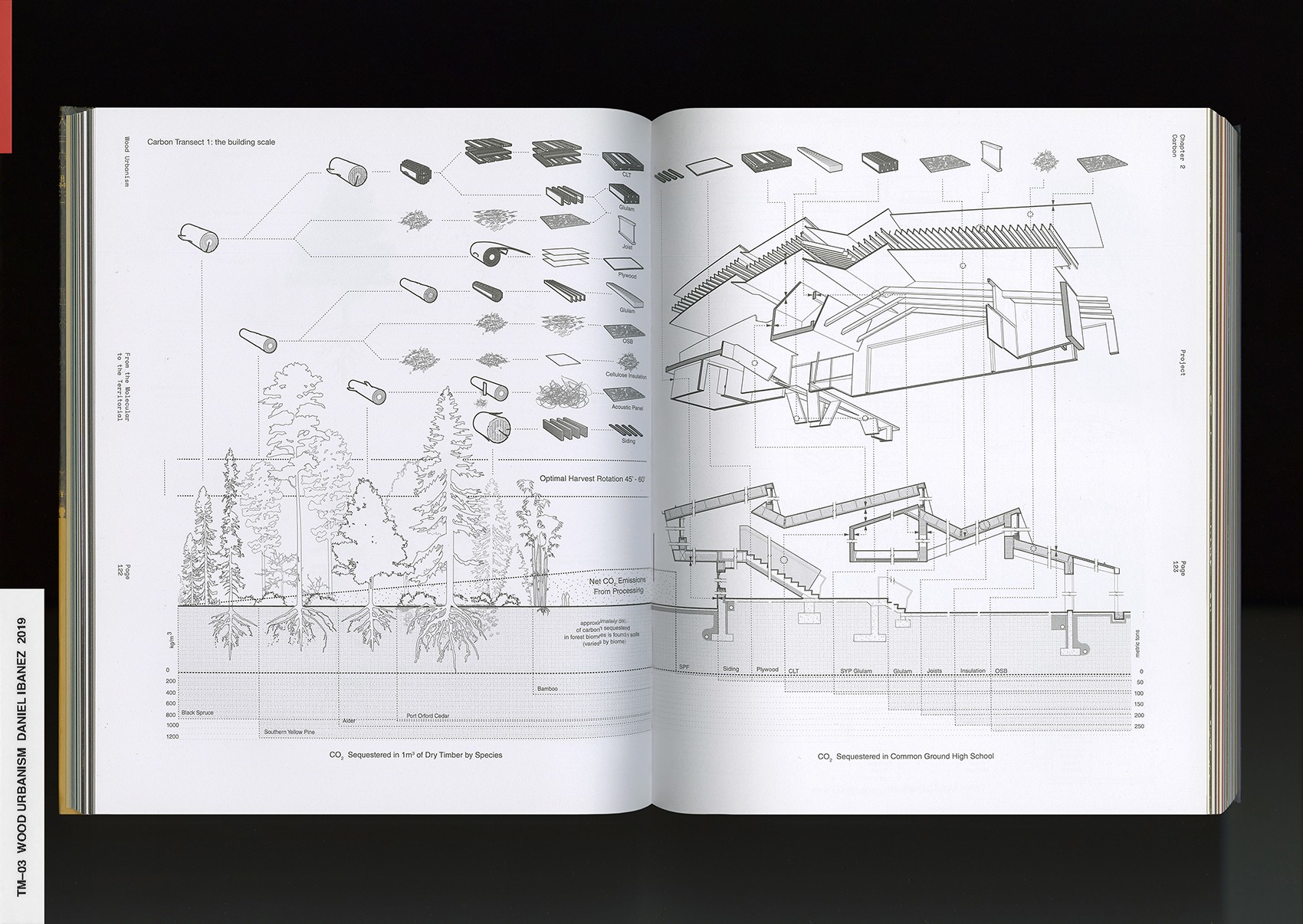

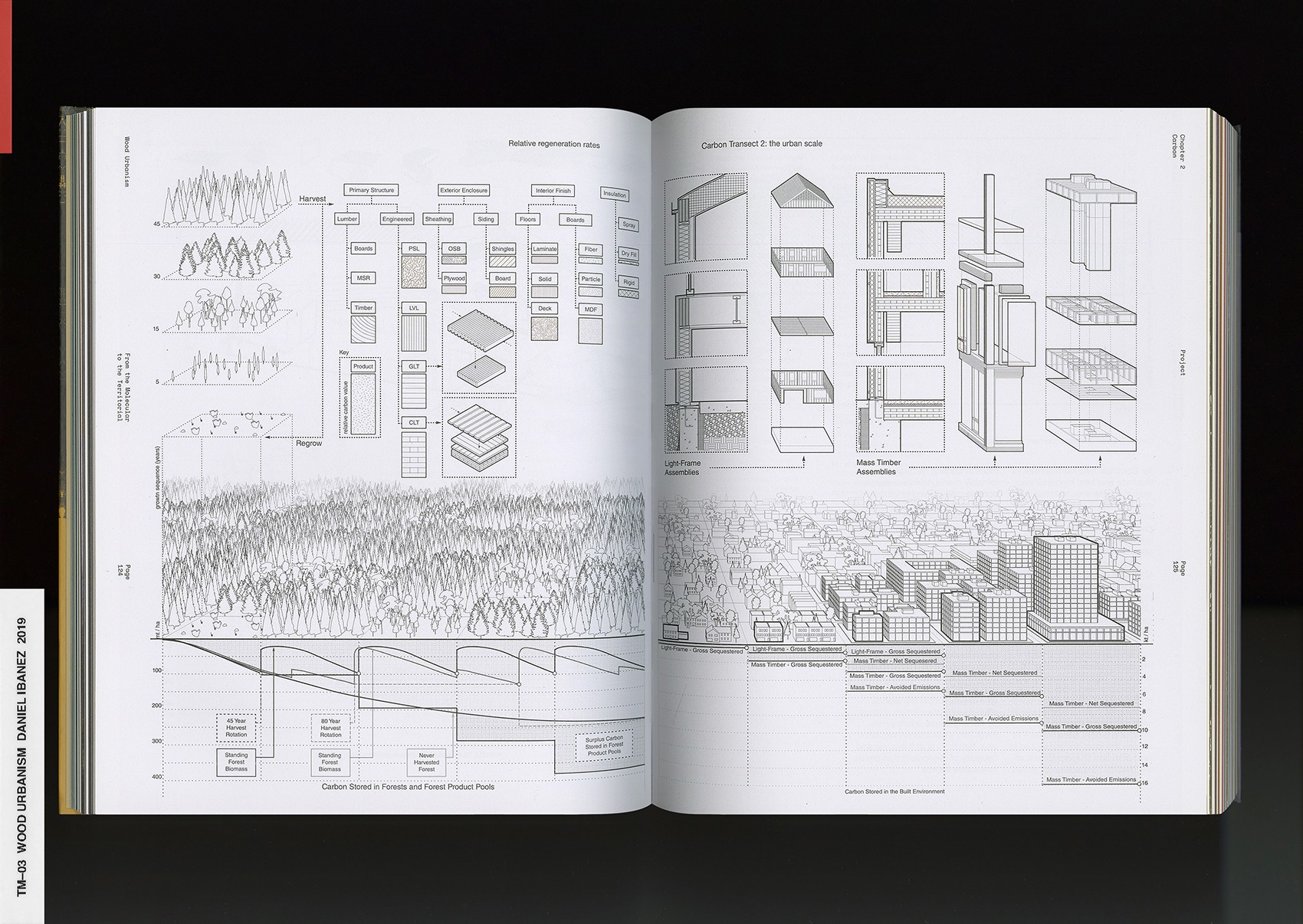

Nearly everything and anything to do with material culture02—manmade and natural. Anything about substances, from how wood03 has been coming from the forest for a long time in different cultures, to how things are made: basketmaking, handmade crafts04, and weaving textiles05. And then to high-tech materials06; starting from metal, to glass07, to new contemporary material innovations08. This idea of material culture’s relationship to our life in society and civilization09 is for years a continuous obsession found in the books I read and collect.

NR

Was there a certain moment in collecting that you had, maybe not some kind of big realization, but where your thoughts about materiality crystallized in a certain way?

TM

Gradually I realized that as human beings, we are subjected to material culture, and that really forms a solid basis of civilization. As a society we make a value system based upon material culture that comes from natural materials and how things are made10.

It’s a common thread: if you want to talk to anyone from another culture, you can start a conversation by sharing ceramics and textiles—two crafts that everyone shares no matter where you go. The most remote village in Africa has these crafts, and in China they have them, too. I am very much interested in what we have in common. And of course it relates to having the three basic survival necessities: shelter, clothing, and food. Ceramics are the vessel for food, and textiles11 are for protecting ourselves, and a lot of textiles reference building culture (houses) as well.

NR

When you arrived at Harvard in 1995 the curriculum was lacking in terms of materiality. You introduced courses on ultra-materials based on your own experimentations. In your work12 you have utilized textiles that distribute sound by utilizing a particular geometry so a performance space does not need speakers or amplification. Or in retail spaces you have applied a polymer resin which has a microscopic structure that creates a teasing appearance—making windows appear blurry from afar which become clear from close.

This common language of ceramic and textiles—as a basis of your work you have interest in taking traditional vernaculars13 of ancient materials and applying them as techniques in a contemporary14 practice. What is an example of this as it relates to these 2 essential elements?

TM

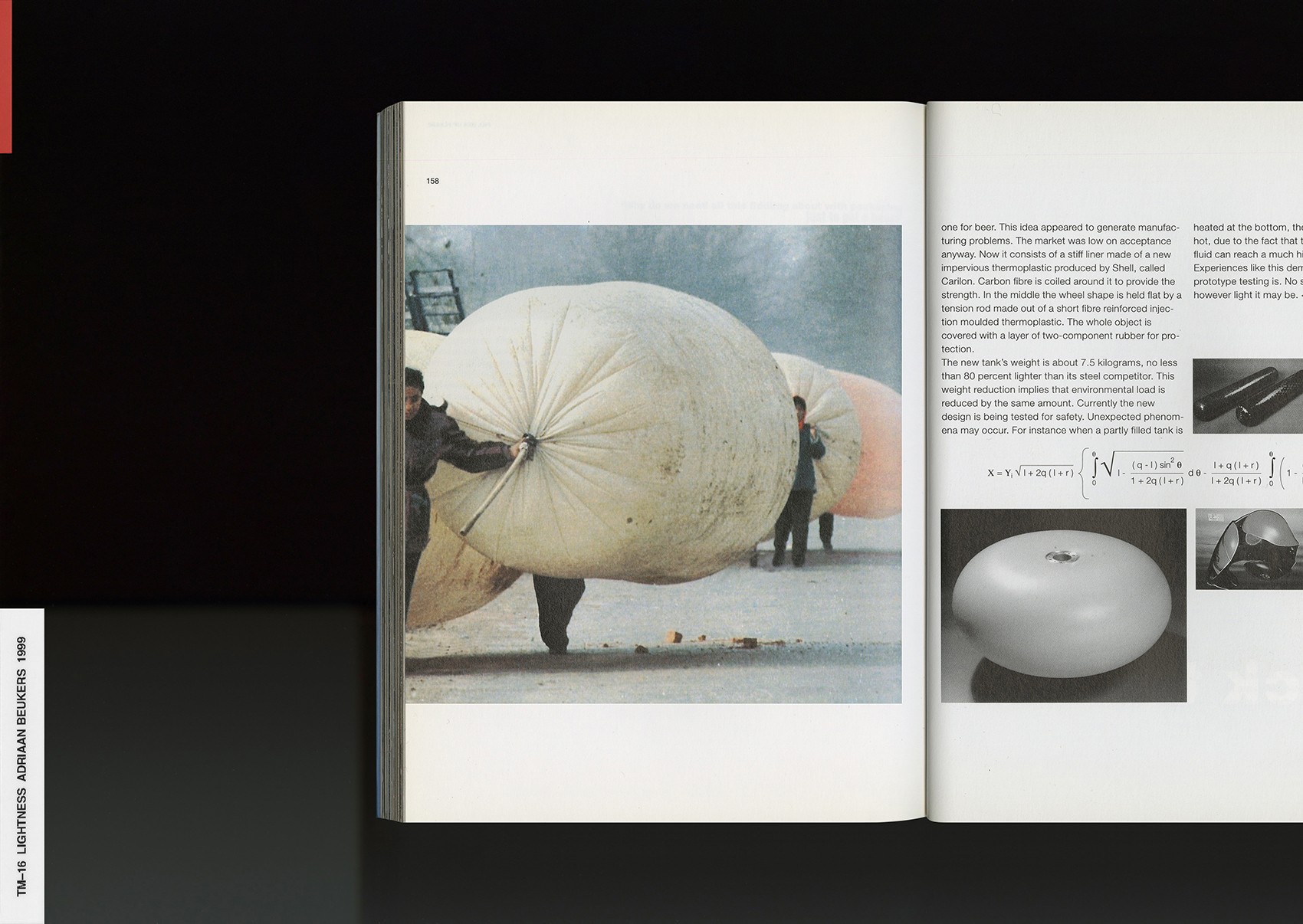

Membranes are very interesting. Membranes are living textiles15. It’s interesting to see how high-performance membranes are replacing glass. They are much lighter, you can create layers like clothing because they have pockets of air. So if it gets too hot, you can deflate them to control interior temperatures. You can now also print different patterns onto them to protect against sun. They can open up, or different parts of different areas have different heating systems built in. Membranes16 constitute a very large part of contemporary material innovation.

I founded a nonprofit called which is developing a prototype for a portable with a Japanese membrane manufacturer. We are just about to file a patent for an air beam system built with membranes. The whole thing is a membrane made of textile—its structural basis is air and water. So, in a way, it has the minimum possible carbon footprint, but really optimizes and maximizes the potentials of textile craft. This particular textile requires post-digital examinations and advanced acoustical modeling strategies and fabrication techniques.

It comes from an structure which already exists, the military uses it, but it hasn't been developed in the last fifty years. For the material of the membrane, we will be using something specific, but it can actually be any dense material which can retain air, and part of it is dense enough to retain water. Then it just needs to be pumped up or filled up occasionally, like bicycle wheels. Basically, it's very low-tech “high tech.”

I've been wanting to build a concert hall, but it turns out concert halls are incredibly expensive to build, and they are not profitable, even some of the most famous concert halls, they have to run red—they depend on donations. So the challenge of Paracoustica is to come up with a typology which can be shared by many music groups and orchestras, and can travel to more communities to prevent the obsolescence of the concert hall typology. And the idea is to make it portable. It’s kind of an ambitious thing, but that's actually an important goal that I'm working on right now.

NR

How is the AirBeam used in the military?

TM

Deployment. If you have an AirBeam hanger you can go into a military base and pop it up. You could even hang military vehicles from it. So, you can actually suspend it and then repair it or carry it and then deflate it and deploy it somewhere else.

NR

Experimenting and innovation—to the public, these two words are romantically opaque. From your perspective, what is essential to understanding these processes?

TM

I think innovation doesn't come in one huge leap. It's a series of small steps. Accumulations of small discoveries, followed by incremental implementation. And then it all adds up. Innovation is not a single idea—it's incredibly incremental and additive. Even these small discoveries can change the way we think about things very quickly. So I think every step of the way—problematizing “what are the issues?” and “what are the solutions?” filtering issues of sustainability, supply chain, accessibility, will eliminate many solutions which are not possible. And then you end up with small nuggets of potential. In a way it's very systematic, innovation, and so is experimentation. It's the elimination of what's not possible and focusing on goals.

NR

Your expertise in the material sciences has also focused on the relevance of the unseen––as a type of force and surface. Could you explain the importance of the "immaterial" and trace the origins of your thinking?

TM

Sound and scent can perform, inform, and transform; their impact is strongly felt even in the absence of material artifact in the traditional sense, making them some of the most efficient "immaterials" for use by designers. (Imagine, for example, being able to codify boundaries and thresholds without built walls or other hard structures.) By exploiting all of the senses, it is possible to create a multi layered experience that evokes a transparency of time, space, memory, and feeling.

As Maurice Merleau-Ponty17 observed, “My perception is not a sum of visual, tactile, and audible givens: I perceive in a total way with my whole being: I grasp a unique structure of a thing, a unique way of being, which speaks to all of my senses at once.”

The sense of smell has a powerful connection with memory and emotions, and represents an untapped potential for our experience and perception of architecture. Through smell we can create a language of recognition, or perception through association. Odors catalog significant memories in the brain, and those memories are involuntarily recalled when a person comes into contact with the smell again, thereby collapsing the space and time between two events. Whether the memory is recalled five years after the initial event or twenty-five years later makes no difference; smell memory, unlike visual memory, does not fade with time.

In Western culture, however, seeing has always held a preeminent position because it is the primary means by which we acquire knowledge. In fact, 90 percent of all information is received by our eyes and sent to the left hemisphere of the brain, where conscious thought is processed. As Martin Heidegger noted, “Even in the early stages of Greek philosophy, and not by accident, cognition was conceived in terms of the ‘desire to see.’” In our culture's search for truth, the eyes have been given primacy, for “seeing is believing." Western architecture has been greatly influenced by Plato, who considered sight and hearing to be the noble senses because they put us in contact with the world of perfection––geometry and music––not the physical world of touch and smell.

Whereas sight has been linked with the intellect, smell has been associated with primitive instincts, sex, disease, and decay. The Egyptians enjoyed the erotic pleasures of perfumes and used them for ritualistic offerings. Plato, on the other hand, considered odors to be vulgar and feminine. At the time of the Enlightenment, like Rousseau praised emotion, smell, and eroticism, while others believed that “as the sense of lust, desire, and impulse [smell] carries with it the stamp of animality.”

Negative associations and cultural taboos surrounding smell have impeded much serious scientific investigation. Until recently little was known about how the olfactory system works. In fact, even today we do not know what properties of odor molecules are associated with their smell. There is no relationship for odor like there is for color between and color perception, or for sound between frequency and pitch.

The in humans is evolutionarily one of the oldest parts of the brain, and smell is the first sense to emerge during fetal development. The , located at the top of the nasal passage, contains receptors that are in direct contact with the air we breathe. This outcropping of the brain is connected to the , which plays an important role in perception and memory, as well as emotions and motivation. If the sense of smell provides a direct neurological link between our physical environment and our feelings, moods, and memories, does that not have an impact on how we perceive, understand, and relate to architecture?

NR

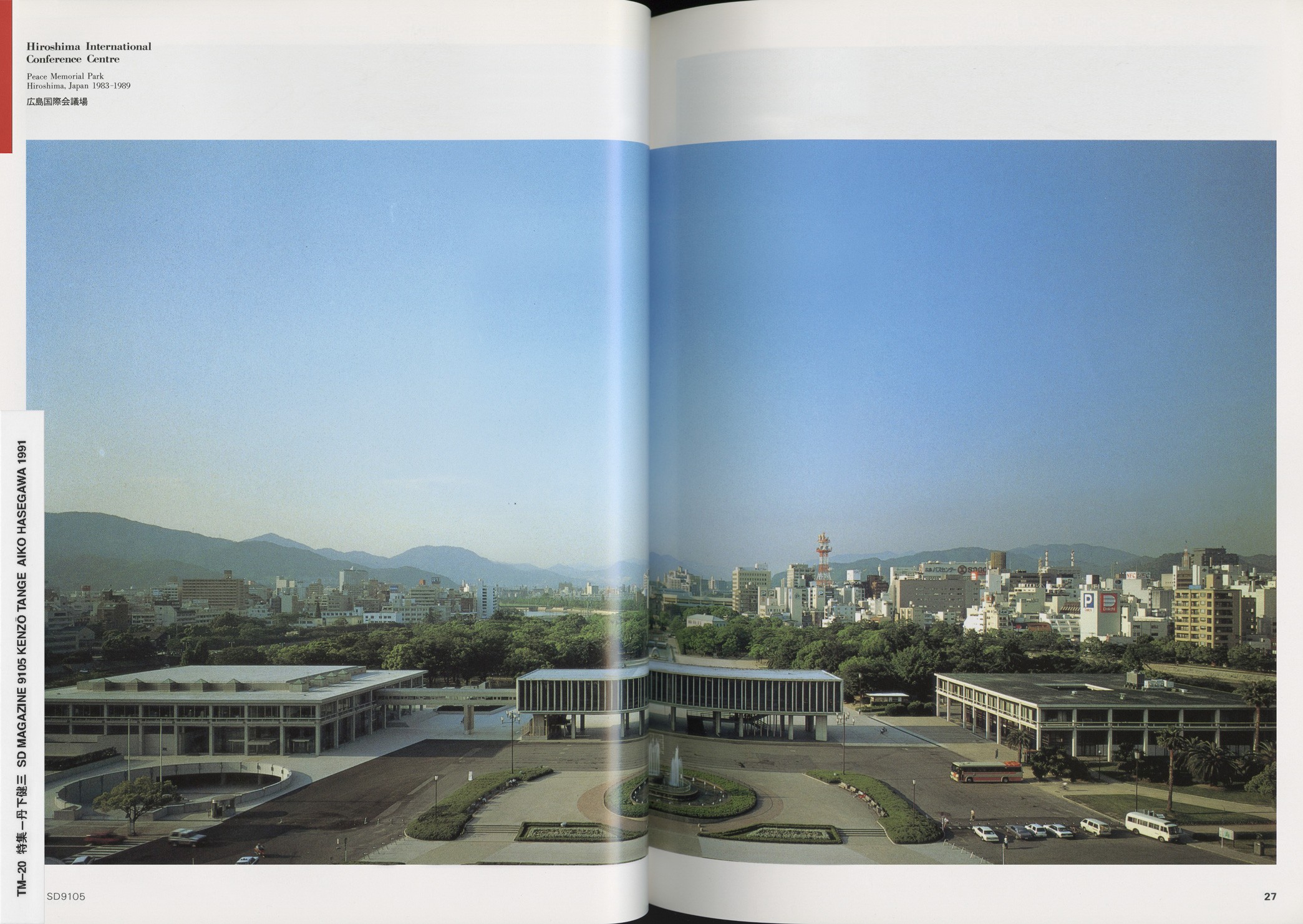

Growing up in during post World War II Japan, you have spoken about how viscerally the consequences of war affects a nation and its people. When visiting the designed by as a child, you described that experience as very impactful in a simple and dignifying way.

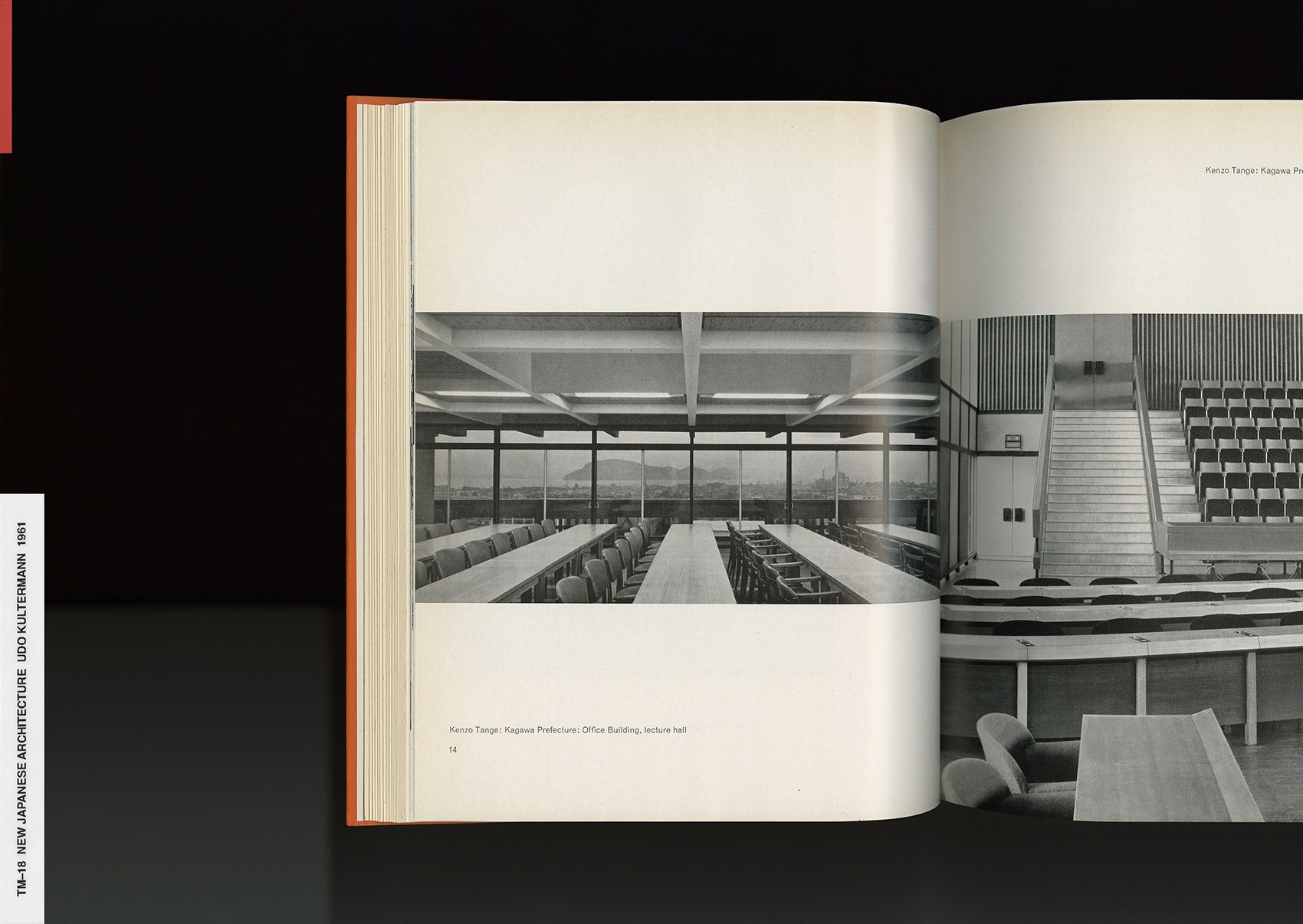

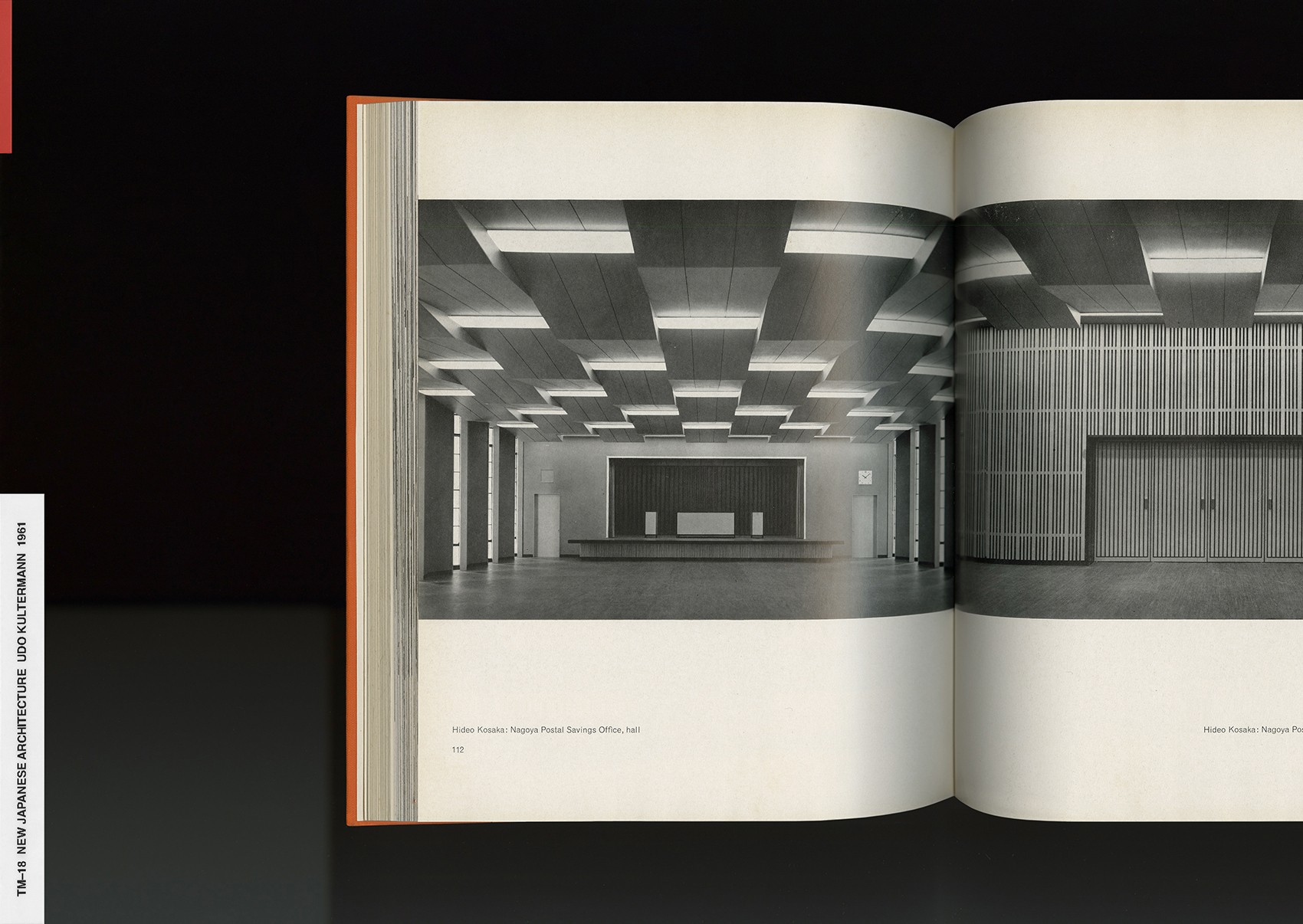

How did Kenzo Tange’s architecture affect your understanding of what architecture could be?

TM

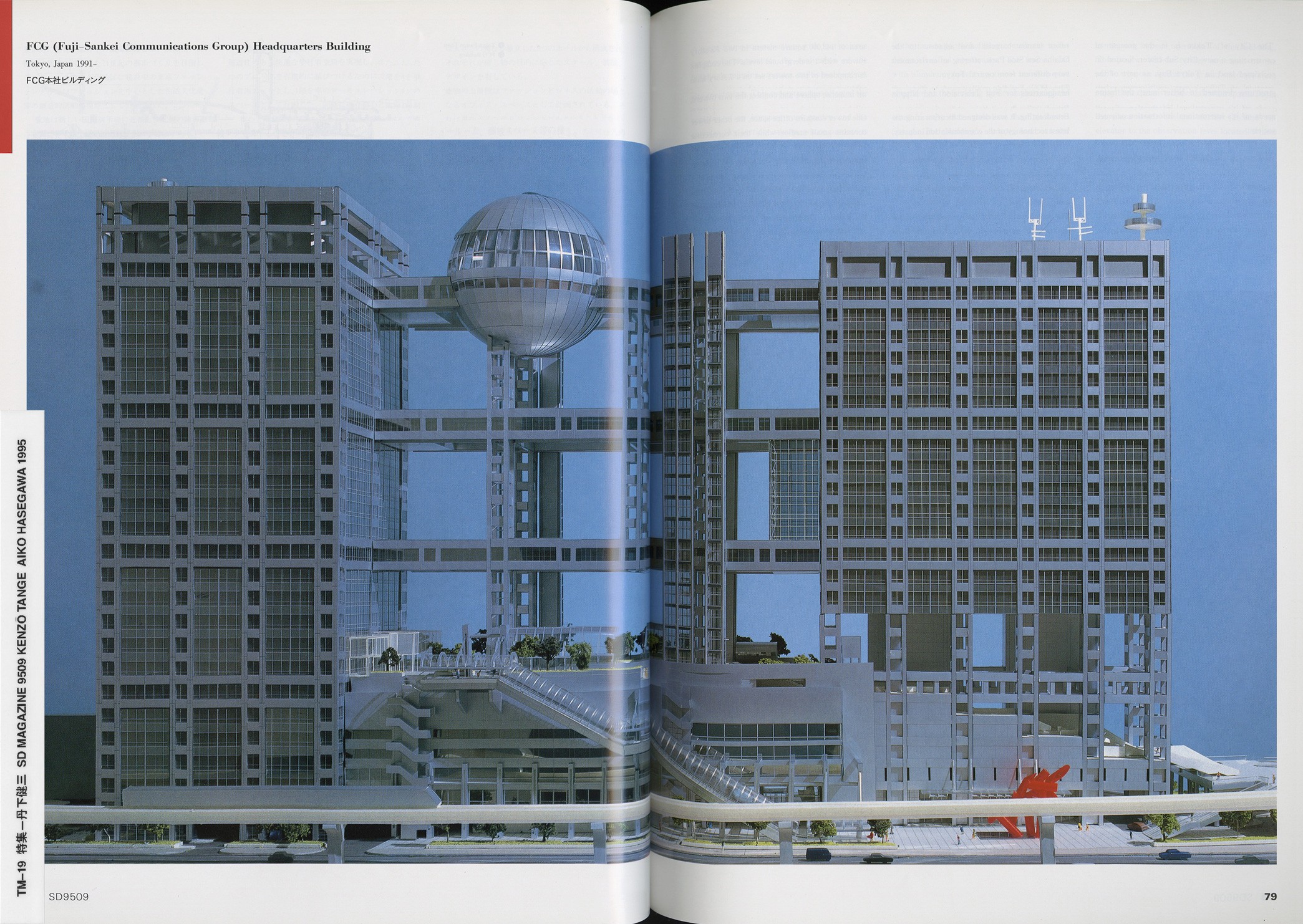

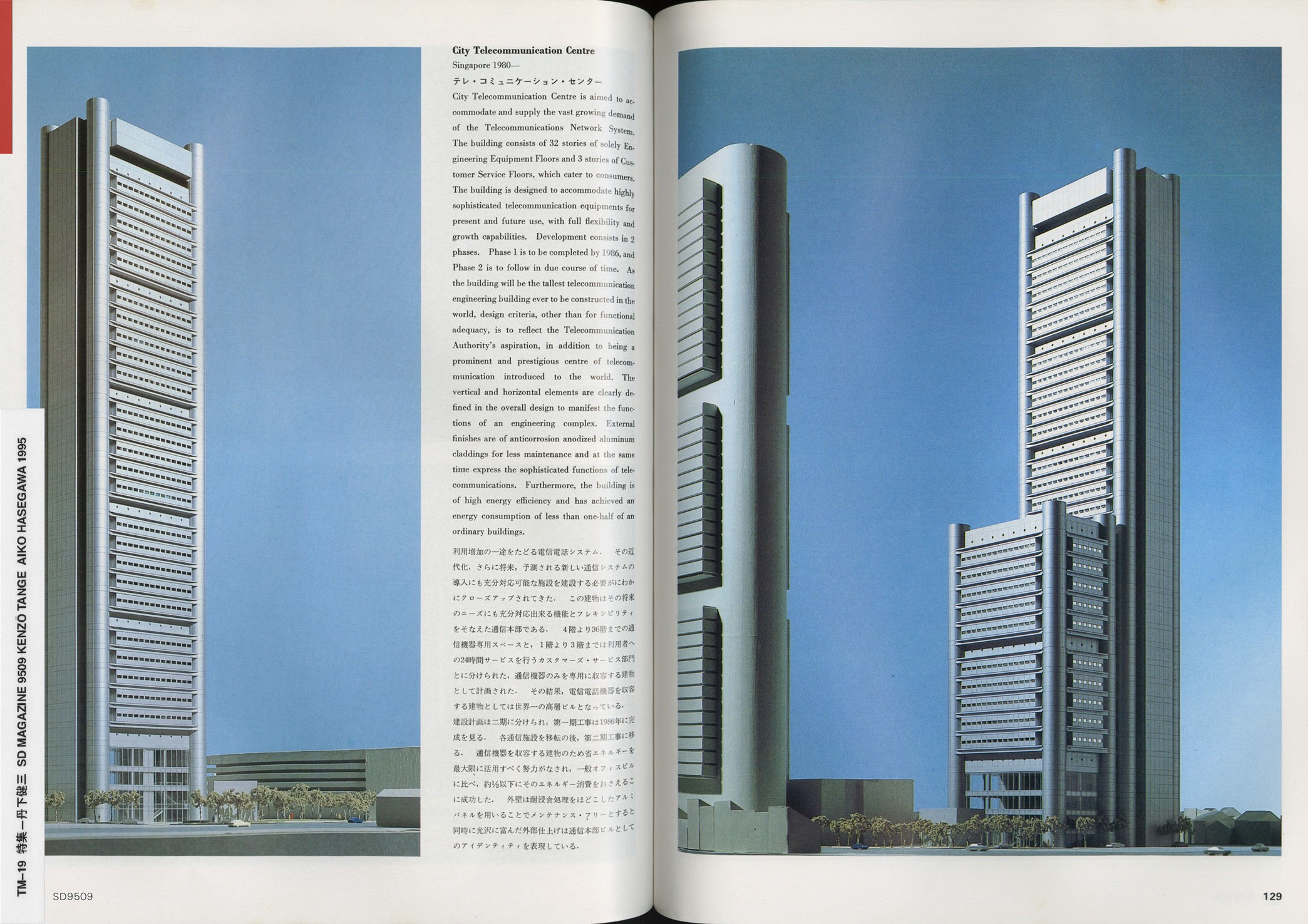

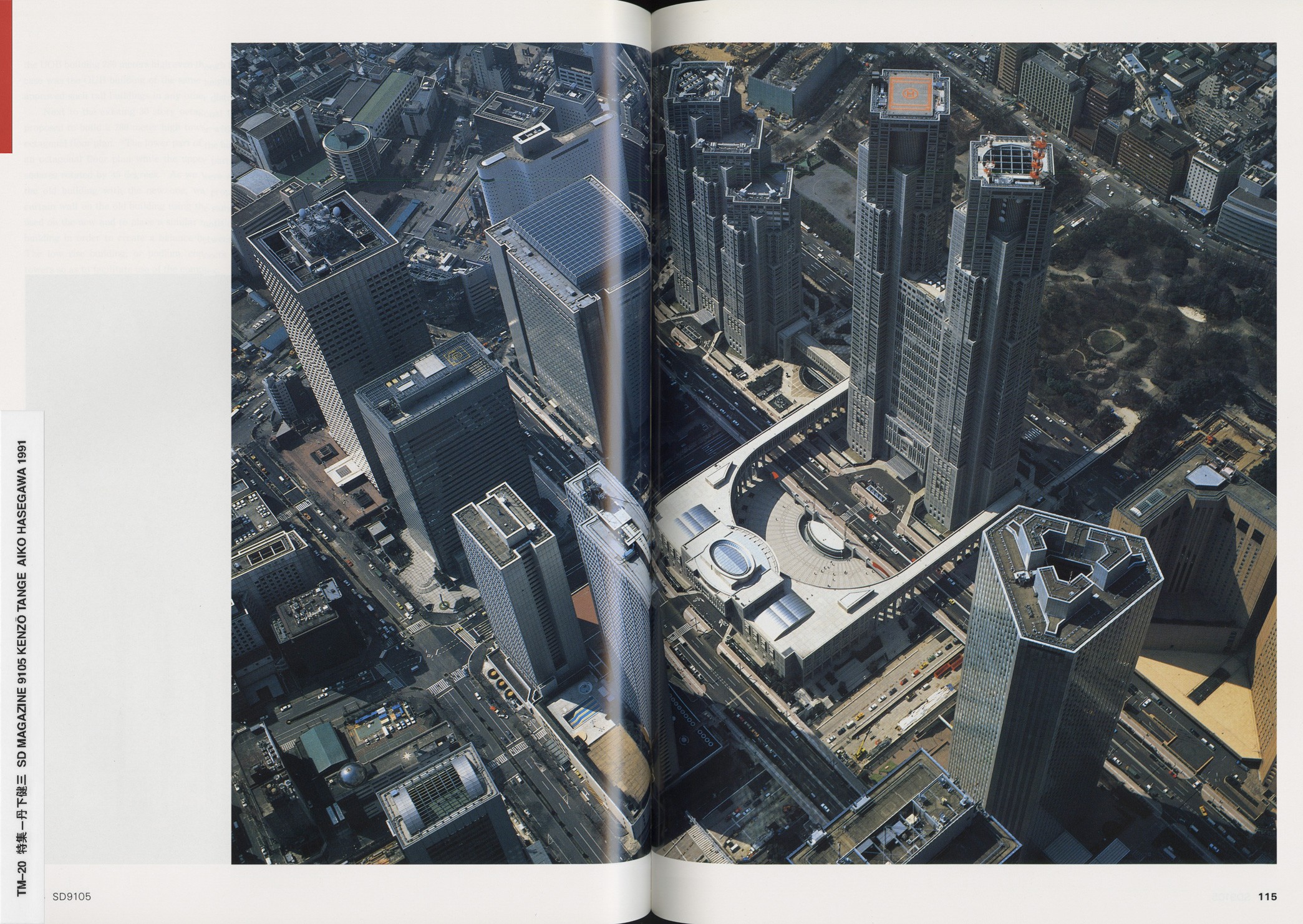

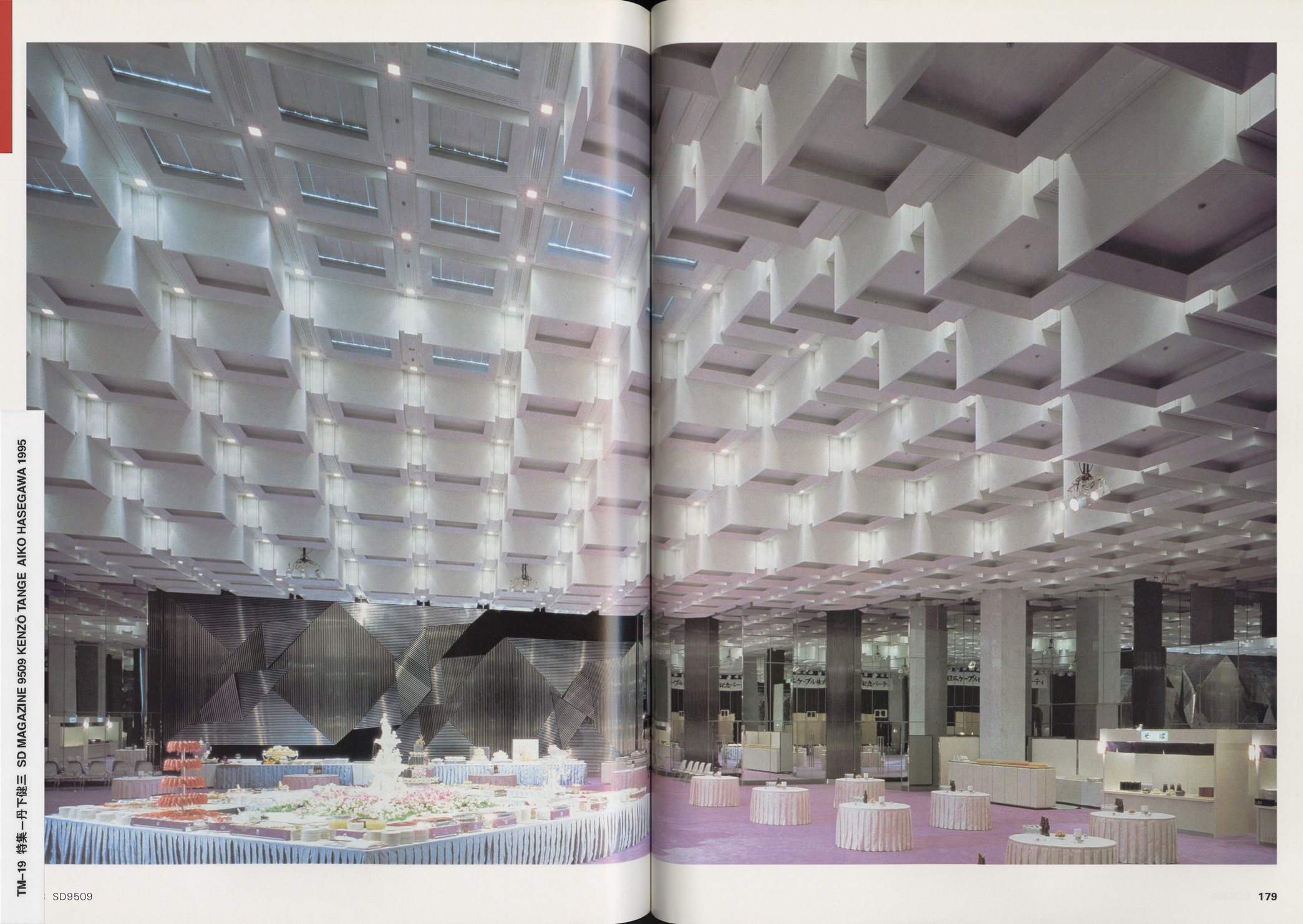

With architecture18, there's always a story associated with the personhood of the architect. If you look at Kenzo Tange’s work, it's highly monumental, highly powerful, highly dominant, sculptural, and expressionistic. But when you look at the story of him in relation to the Hiroshima Monument19, you will start to understand more deeply what he tried to achieve with this architecture. And I think that really affects me more than anything, his motives.

He went to high school in and grew up in . The day that Hiroshima was , he was called home from Tokyo on a train because his father was dying. During the train ride home, he found out that Hiroshima was bombed. And then his father died, and his mother also died fairly soon after, and he lost all his classmates from high school. As a student at the , he really wanted to contribute to the reconstruction of the city. Despite the danger of , he fearlessly went into the basement of the Hiroshima City Hall to start planning the city’s recovery.

So, before he built that Peace Center, he had this personal experience and relationship to Hiroshima. I think from that, the young Tange figured out that as an architect his mission was not only to build buildings, but to reconstruct entire cities20—and a civilization’s psyche. He was invested in the future identity of Japan, so the ascent of his career was partly driven by a nationalistic ambition.

He really started from nothing. He started from immense loss. So, if you know that story, which is not often told, then you start to think about the role of the architect very differently.

NR

Growing up during this postwar period, what books shaped your coming of age?

TM

When I was growing up right after the war it was very difficult to get books, but luckily my father would travel to Tokyo every week and would get me a book. I also got books from my cousins. I was an avid young reader. Everybody nicknamed me a ‘print child’ because anything that was printed, I would read. It didn't matter—newspapers, advertisements, I would just read it. Anything. I was very hungry. That's how kids are when they are deprived of resources. So, I was a voracious reader and I was reading a lot of things. Later I was able to come to terms with reading classics, and by age 14 I read nearly all the Japanese classic writers. Today, I'm a very strange reader. I’m constantly reading at least fifteen books at the same time. I read fiction or essays at night. When I'm doing research I always have twenty books on my desk, it’s always a huge mess.

To the question; there's a book by called The Makioka Sisters21. I was drawn to it both for nostalgic and progressive reasons. It tells the life of women and sisters living in the Western part of Japan, just before the beginning of World War 2. It elegantly describes customs from that period. The depiction of this lifestyle is very delicate and fragile, and also it takes place near where I grew up in Kobe. So I could relate to their culture and lifestyle, like how my mother or grandmother would live. Tanizaki is critical of the lifestyle in Tokyo which is more business-like and efficient as opposed to the slower, more deliberate pace of this region. So [it’s about] the decline of values, and what values they hold on to, and how women have lived and will live. There are lots of implications of modernization, but also keeping tradition, aesthetics, and culture.

In Japanese the book is called Sasameyuki, which means fine grain snow. It’s a very poetic connotation because it's a noun, but it really describes the state of how snow is falling. Tanizaki uses it to describe the decline of a family facing modernization in Japan. And this fine grain snow is also a description of how cherry blossoms form in the spring—very fine white petals. It has a deeper meaning because this is when the flower is at its fullest, but it's also very fragile—how things will fall apart and trees become bare, but it’s also about renewal. So it's got a lot of meaning, and the title I don’t think is translated as well as it could be, but it's very beautifully written.

The protagonist Yukiko is named ‘Snow Child’. [That's why the title of having the snow has significance because it identifies who the protagonist is]. Her younger sister Taeko is the one I was attracted to because she was a rebel and would choose her own suitor and would make her own dolls and dresses. She’s very interested in making things and wanted to go to France to study dressmaking. She starts making her own decisions about her own life. The protagonist is very, very conservative, but the writer puts in this younger sister who talks about the idea of a future of self-reliance. So I was very attracted to this younger sister when I was reading it when I was young. She made a big impression on me growing up. In terms of classic literature, that's my favorite book.

NR

Did that cultural duality translate to your experience growing up?

TM

So this story is about the struggle of transition between isolated traditional culture and modernization and Westernization. All families were exposed and vulnerable, and needed to figure it out. So, it's an allegory of deciding how some will live going into the future, or how some will stay traditional and deny modernization. Some members of this family stay traditional, but some members, actually, like Taeko, go beyond it and become adventurous and embrace modernization.

Then there’s another book later on which I was very much influenced by; Yoko Ono's Grapefruit22. She happened to be in New York under similar circumstances—her parents were stationed here, like my parents. Her father was working for the Bank of Tokyo and she went to Sarah Lawrence. So I knew about her artwork, her installations, and then Grapefruit came out. That's my favorite book. It has a very different kind of heroine. John Lennon's story is interesting, but less so than her own idea of performance. And she always worked with context—transforming a site in the city; how the public will perceive it—and the vulnerability of being human, being a woman, all of that really had an effect on me.

NR

Your architectural approach rejects the notion of having a ‘signature style’, but rather favors a set of adaptive ethics. You have said;

"I always say that in architecture in my era, styles just do not exist for any of us anymore. To try to make something look like something else artificially is a totally idiotic approach, because the world is very complex and, as an architect, one has to embrace the context…”

What other architects have served as historical models for this kind of approach?

TM

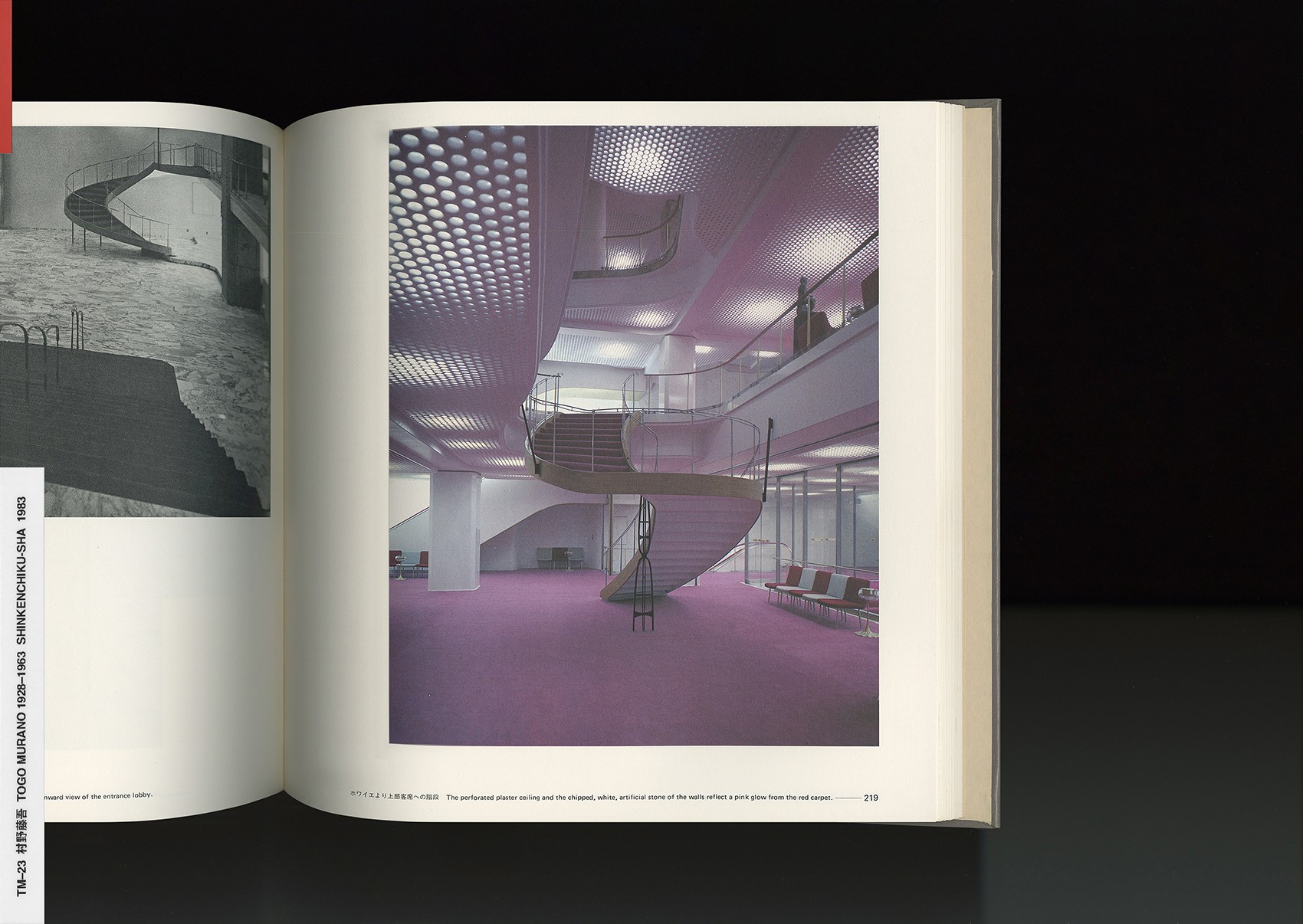

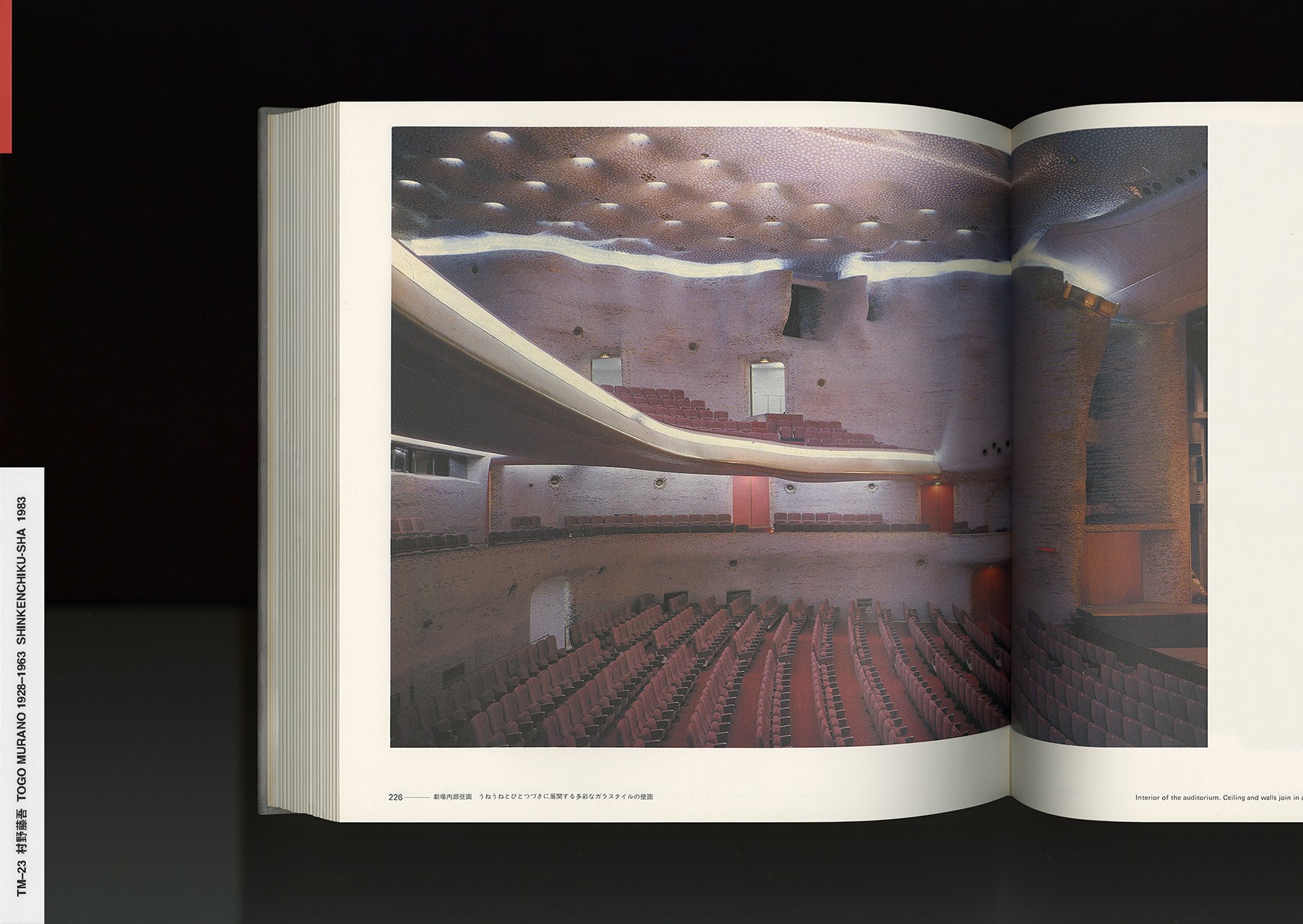

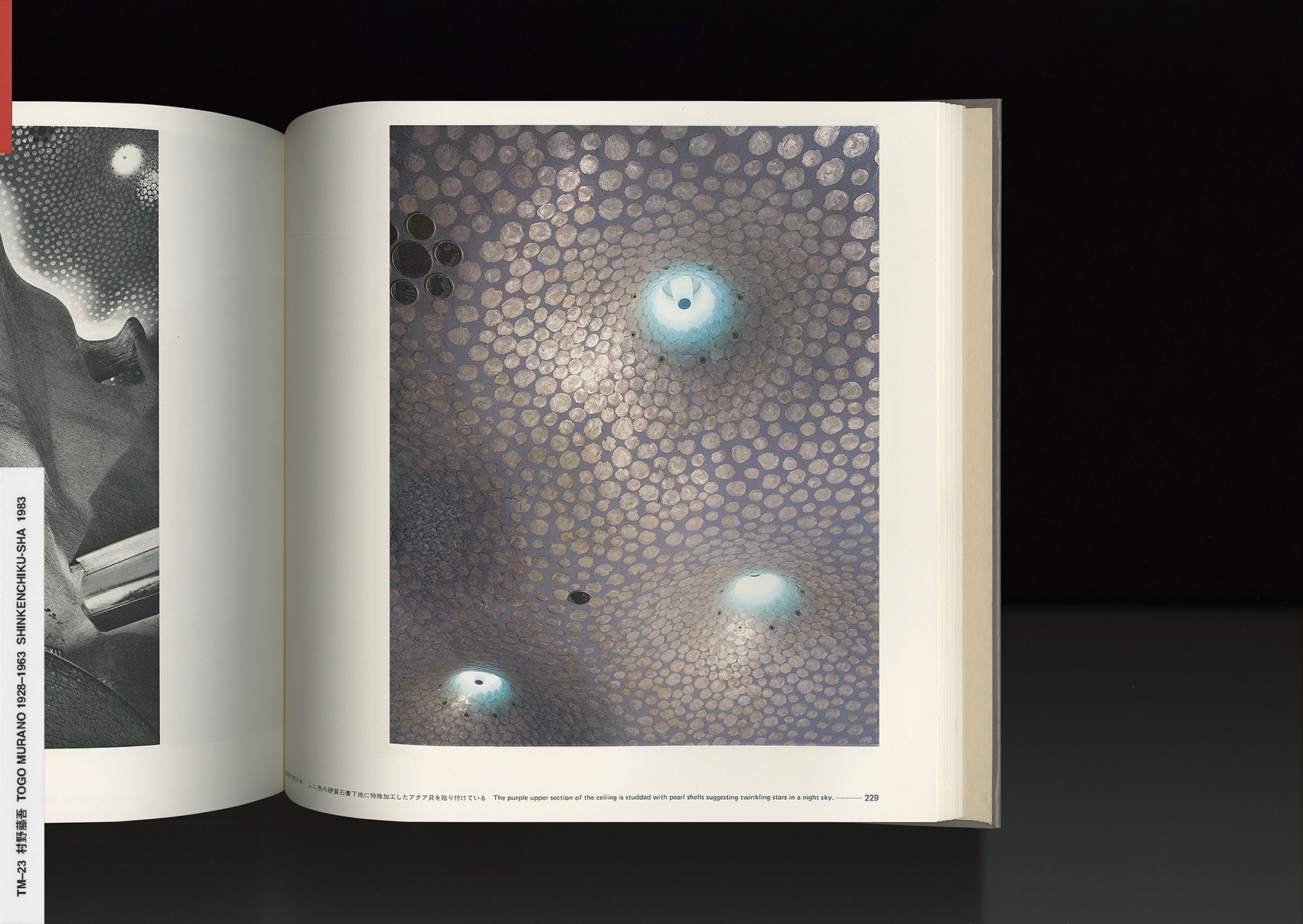

Togo Murano23 when he did the . It’s incredibly elaborate; Inside it looks like a gallery but it’s completely suitable for a particular theater goer experience. They built it for kids so the chairs are low and there’s some scale for them—it’s very particular. And then he would do a train station which is very different from the theater. And then he would do an amazing hotel different from the train station. So, his projects fit into their contexts incredibly well, but they still look like they were designed by the same person. There must be a sensitive reading of the context to come up with something new. You want to design something that can only be located in that particular place—instead of imposing a cookie cutter style all over the place, which happens to many architects who have a recognizable image.

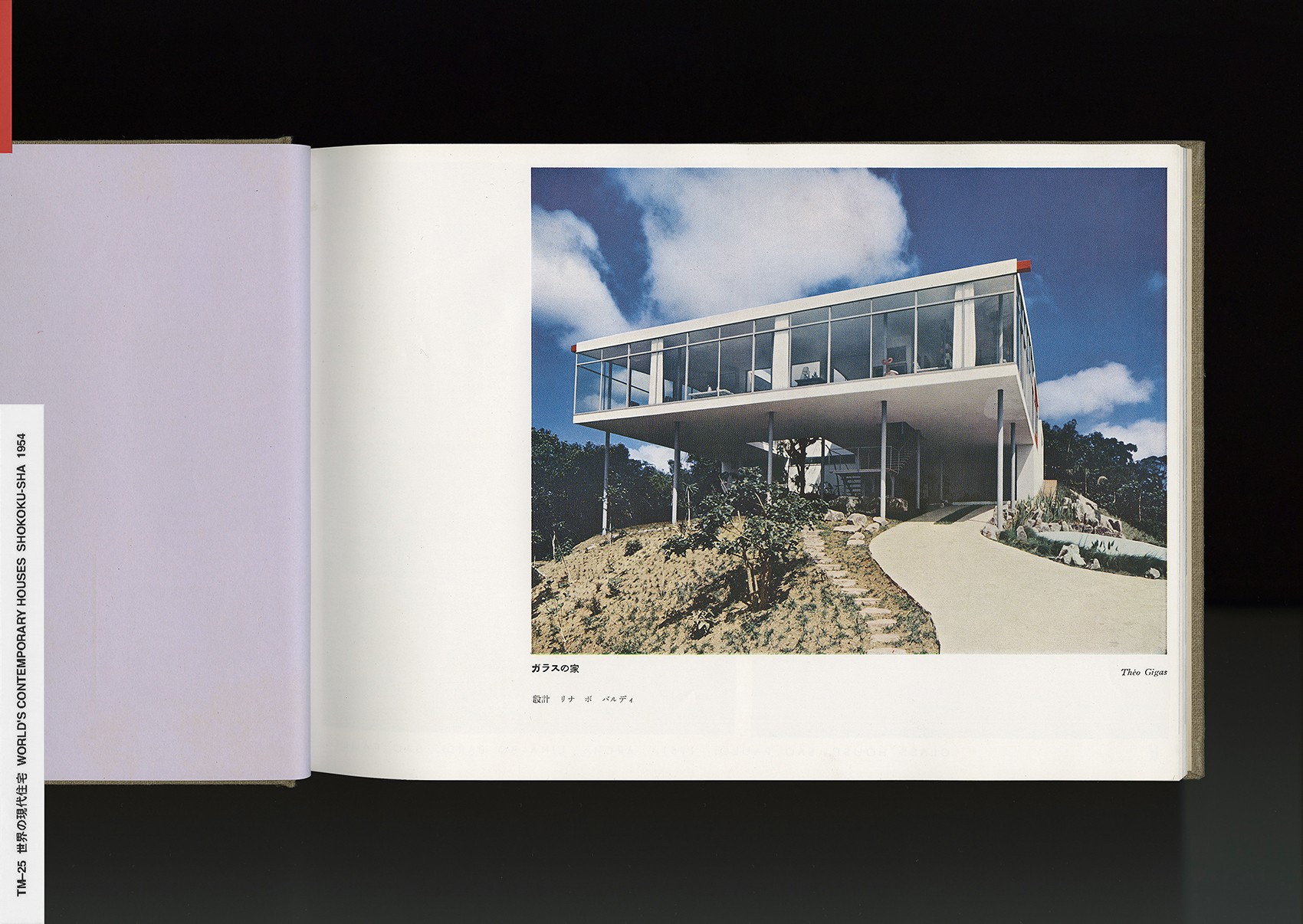

Togo , and also , adapted enormously to both program and culture—it’s very distinct architecture, but it’s so rooted in place24. Lina Bo Bardi25 is another architect who worked like this. Contemporarily, do that also. Their buildings are very different—each is very specific to the place and the program. I think that type of architecture probably will survive better than signature building styles.

NR

The signature form—do you feel that is motivated by an artistic impression, like a recognizable brush stroke. Or is it a commercial gesture of branding?

TM

It’s a brand.

But architects like are very nimble with their branding. You can recognize a Kengo Kuma building, but none of his buildings look alike. Same thing with Herzog & De Meuron26, they are very nimble in re-adapting for specificity27—and I think that is more artistic. They both have a brand, of course, but it's a different kind of branding.

NR

In the male dominated field of architecture—you said you had no mentors or role models that were women. The fields associated with architecture suffer from gender imbalance as well; such as engineering, construction, building management and real estate… Were there female historical figures you gained guidance or mentorship from in books?

TM

My architectural hero is . She was an amazing person. She was connected to society, communities, and construction crews. And also the fact that she's originally Italian, and established an identity in a place different from her place of origin (Brazil), resonated for me coming from Japan and establishing my practice in the United States. Navigating that territory, not only being a woman, but being a migrant as well.

NR

How about in design, generally?

TM

Charlotte , a furniture designer. She is significant because the Imperial Japanese government, before World War Two, invited her to help develop Japanese crafts into modern furniture. She worked directly with craftsmen to conform Japanese craft making to a method of standardized production. Many craftsmen did not know how to introduce their crafts to Western production models. And she introduced things like chairs, which was not a typology that previously existed in Japan. At the same time, she was helping furniture companies establish themselves so they could eventually make furniture for buildings, for example Kenzo Tange’s buildings. She really encouraged not only furniture design, but also interior design and design culture in general.

She was a communist, like really political, and to this day I have no idea how she accepted this Imperialist government’s invitation. But I think beyond the political things, she actually saw the artistic potential. Now, Japan is a leader in the design community and without Perriand28’s intervention, it might not have ever happened. It’s an incredible contribution.

NR

You have produced contemporary additions to Modernist works by to . Your approach is to never imitate. Contrast and contradiction are your guiding principles when having a dialogue with a master work.

“A contradiction—you make up your own fictional narrative. History is really a fiction built upon facts. It's interpreted all the time, it's never been a truth. History is fluid.”

Can you talk about your approach and how you developed this point of view?

TM

You know, history is not about the past, really. History is about the story of an individual interpreting history. Historians cannot be unbiased narrators. Every history is a story, and then yes, there are facts—which are important, but the way you connect facts and then make diverse narratives is super interesting.

As you can see, provides false narratives, and a lot of times they skew the facts, and that's a problem. It can be used dangerously, but it can also be used productively. I think that's what makes history rich. It's not about the past, it's about projecting into the future. So when I teach students, I ask them to make their own story based upon their research. But it's a story—so that's kind of their own reality. And based upon that reality, they can develop diverse narratives and then communicate the story to others. It's not as if you have different opinions, but you have different stories to share. It’s not about controversial opinions, but about the way we each look at life very, very differently—and that enriches everybody.

NR

Especially in design, where certain styles or people are consumed as monuments. Their design principles are observed and emulated as solid states. Not malleable.

TM

If you look at history, it's so interesting to see what people have picked up and connected as facts. Especially architectural history, which is so extensive—its material is available everywhere—you really can see that it's a fictional narrative.

NR

Your senior thesis “Places of Transaction” (Cooper Union) was about people and merchandise; the idea of how goods are moved and presented. This thesis became the full scale model for Rei Kawakubo’s first in the United States—and your very first commercial project. What were the books that informed the research and development of “Places of Transaction”?

TM

Invisible Cities29 by . It was published in Italy in 1970 and translated into English in 1974. My thesis was in 1976, so I immediately got the English translation. That became my Bible. It's about the conversation between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan, a fictitious emperor. Marco Polo would come back and tell him about all these cities, the relationships between cities, and their economies. It's really a fantasy, but it's an amazing text about urban design and urbanism. It was significant to “Places of Transaction” because Venice is the first place where a foreign exchange and credit system were established to help allow merchants to take risks to move goods and trade.

At the very end of the story Marco Polo tells Kublai Khan, “Every city looks like 50 cities in total.” But he says, “It's all about where I come from, it's all about Venice.” So the city where you come from—as a memory—is always there in your mind, and you’re projecting it onto other cities you visit to try to form a basis of place. So it’s about how fantasy and reality are intermingled, and that's where the human memory is. It really shows that a city is constructed of human experiences and the memories that are associated with it. That makes cities such an asset to human culture.

NR

How did the first city you experienced, Kobe, inform your lens of New York City? And every other city you go to?

TM

Kobe is a very interesting city. It's compressed between a mountain range and the ocean. The city itself is very linear—one is constantly aware of the to the south and the to the north. One is always traveling back north and south, east and west. So the city is oriented by this relationship between nature and urbanity. As one moves closer to the mountains, the city becomes incrementally different along the coast. That microcosm is always in my mind. That's actually my personal lens which I impose upon nearly every city. If you think of it, nearly every single metropolis is oriented to a body of water. Even if it's a river, like in London or Paris. Most of the time that relationship exists because of commerce, really. And also the relationship to natural resources because humans need to be in proximity to water in order to sustain themselves.

[Pause]

I just have to mention that I see a book30 by one of my favorite people ever right on the shelf—. I knew him and worked with him.

NR

What did you do together?

TM

He was incredible. Very rigorous. Very philosophical, but he's ethereal and fragile in person. You can see both sides of it in his work—incredible rigor and technical proficiency—but also an otherworldliness. He’s just in a different sphere. Some of his projects run a chill up your spine.

We worked on Issey Miyake Madison Avenue together. So we came up with this idea of using bridge cables in the ceiling to hang clothes. It's funny, it's actually a tectonic of textiles—it's cables braided together—and so the threads were braided just about perfectly to hang the clothes throughout the whole thing. We developed a system of corrugated partitions. I think it was heavier than he wanted it to be because of American regulations. He really wanted to make it more ethereal. It was a lot of fun. I do miss him.

NR

To the young people interested in learning about architecture—As the former Chair of Architecture at Harvard's Graduate school of Design (the first female to ever hold this position), and current practicing professor, what open source resources could you point people to from Harvard?

TM

Go online, it's called HarvardX—which is a series of curated open-source lectures, not only from Harvard but MIT and Berkeley as well. It's designed, curated, and structured in a way that is accessible to everybody.

Harvard has also digitized and cataloged Kenzo Tange’s archives. It's open source, so anyone can access it. It's constantly available to the public.

NR

If someone is interested in studying architecture, but not quite sure they want to commit to doing it in school. What is an entryway to test that?

TM

HarvardX’s The Architectural Imagination is a really great lecture by Michael Hayes, and also Cities. If they are interested in architecture, instead of reading, you should be traveling and going to different places, cities, and buildings. Looking and experiencing. Learn by being around. I think one can learn a lot by reading, but it's a little too abstract because architecture involves so much of the human experience and visceral understanding. You can't learn about bricks by reading about bricks, unfortunately.

NR

As you have been teaching for 30+ years, how have you noticed the perspective of students has changed towards architecture over time?

TM

This generation's really interesting. I do a materials seminar every year, and I ask students to choose one material or fabrication method to research throughout the course of the semester. They survey energy issues, relationships to vernacular typologies, relationships to light, and future innovations—they go through like 13 different analytical steps. This year, I had 16 students, and everyone picked a natural material. This has never happened before. People always chose concrete, steel, glass, wood, and stone, all the time—that was standard. This year, they picked , , , ceramics broken down into different powderized materials, and rubber. Through that lens, that means they’re interested in relationships31 between material culture and natural resources, and how this research can prevent climate degradation.

And they all studied the supply chain because they suffered from COVID—they wonder where it comes from. Why does this material have to travel 5,000 miles to get to my desk? So, I asked them to pick anything––it's called material biography—then take it apart and see what parts are made of what and where they come from, how they become a finished product. Then they get shocked. And then when supply chains break, you can't immediately purchase an iPhone, or a watch. So they're curious about supply chain consciousness, energy consumption, and the carbon footprint of each material and production method32. This year, these became top points of interest. On top of that, equity and social justice have been big on their brains.

NR

What do you see as a systematic issue in America that could be impacted by architecture if it was more supported by the Government or if there’s more unlimited funds for architecture and urban planning?

TM

For sure it’s inequality. Inequality is huge. How certain people have access to things that others do not. The founding of this country as a democracy, equality—is not happening. We did not carry through that ideal. Why don’t we invest in better infrastructure and better systems and better housing, equally? Housing and real estate excludes many marginalized communities because it is a system built upon principles of extraction and exclusion. And it takes a lot to reverse it. There's a lot to be done. Or else I don't think we can survive.

NR

What would be the first steps that you would take?

TM

Well, improving infrastructure and mobility is one thing. And then of course to make better housing available and make it financially accessible. I think there's a lot of innovation going on, like , in terms of inventing new ways of selling real estate and new types of systems. Something is happening now post-COVID: people are having doubts about finance, real estate, insurance, and the healthcare system—all not serving their purposes. I think a lot of innovative businesses are coming and hopefully that's going to be an impetus for a change for the better, and architecture can follow it.

NR

Looking at the more macro system—based on your experience as a former Chair of the World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on Design, dealing with the future of urbanism. It's a very broad question, but what do you think the city of the future is going to look like?

TM

Oh, cities actually don't change that much. It's very strange—from Marco Polo’s time to today’s Venice, cities actually don't change. They survive through everything. They survived the , they’re going to survive the Coronavirus. It’s the most resilient model of human habitation. So I think we as humans probably evolved more, in the way we live, than cities have.

For example, now we are more dispersed. Statistically, about 15 years ago we lived in a similar density spread to today’s. We were much more spread apart, but the square foot per person kept decreasing to pack more people in to raise real estate costs—It's financially driven, I'm very convinced of that. So in a way, the way we are socially distanced is the way we used to work 15 years ago. In a way it's making its own corrections, I think. Urbanism33 expands and contracts and survives, it's really amazing.

NR

In 2001, in the time after witnessing 9/11 from your rooftop––how did that state of being affect your print consumption?

TM

What kind of print was I reading right after… that’s a good question. Everybody became introspective and sympathetic. Being in Tribeca was like living in a war zone. And in the rest of the city it was like nothing happened. So it was a bit apocalyptic in a sense. But again, being an architect, as I’ve just mentioned, I've seen how cities like Rome have collapsed and returned over and over. After nearly every single disaster, everything but the city is gone. So I know we're going to bounce back. But it will take time.

I go back and forth between Japanese literature and American-written English literature. I read an enormous amount of after 9/11 because he deals with this strange magical realism, in which fantasy saves you mentally, and the world in your mind is bigger than the world of your reality.

NR

Architecture is so permanent, but ideas and perspectives are constantly changing. How have you learned to cope with ideas that live on in your work permanently which you may later perceive as outmoded?

TM

When I am formulating a design, I think of different states of its being, when it's stripped of all the interiors and decorations—its pure structure, what does it do? I have to remember that architecture gets used not just by architects’ intentions, but by users who are creative and oftentimes much smarter than architects—who use and adapt the structures in different ways. It’s very strange because houses remain houses, but their occupants change. They evolve and have many different lives.

I have a very different attitude in which I use the word loose fit, instead of very tight fitting clothes. When you do architecture, which is a really tight fit, it can become obsolete very quickly. I think this does an incredible amount of disservice to society because it's a very large investment in terms of human, financial, and natural resources. I want to design architecture that has some flexibility, looseness, adaptability, that gives the idea that it can transform and evolve with time. I try to think about how to not to make it obsolete; I think of that quite a lot. And then even if it becomes a ruin, did it contribute to society at large?