Elise By Olsen is the founder of the International Library of Fashion Research—the first dedicated solely to fashion printed matter, containing materials exclusive to industry insiders, e.g. show invitations, press supplements, trade materials. This commercial matter is the footprint of the industry, making it a powerful tool for understanding the mechanics of the opaque fashion machine.

NR

At age 14, you received an anonymous email. On the other side of the screen sat a 68 year old New Yorker, living with no cell phone or furniture, only a desk and two metric tons of fashion publications stacked from floor to ceiling. After exchanging thousands of emails, the mysterious downtown theorist shipped his entire collection to Oslo, Norway—providing the seed collection of the International Library of Fashion Research.

EO

At 17, I traveled to New York to meet . My parents had to sign off and submit a paper so that I could go to the United States as a minor. The collection that he spoke about was transcendent, it was his home, it was his way of being. When I walked into his apartment on East Broadway & Essex, I saw a bed, a desk, and stacks and stacks of dusty printed matter. He was completely immersed, which I found to be incredibly fascinating but also so shocking. He was somewhat of a hoarder, albeit a very chic one!

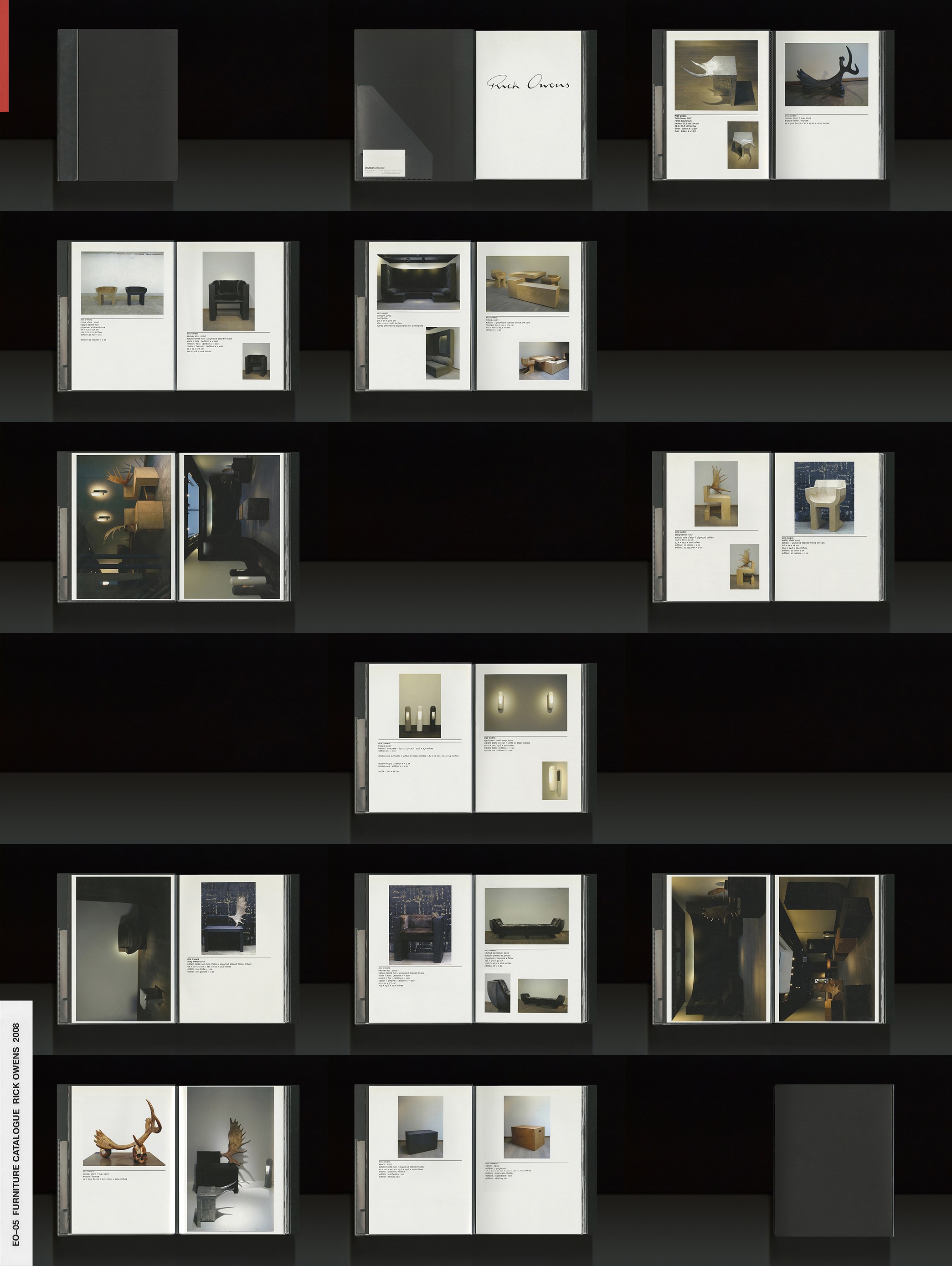

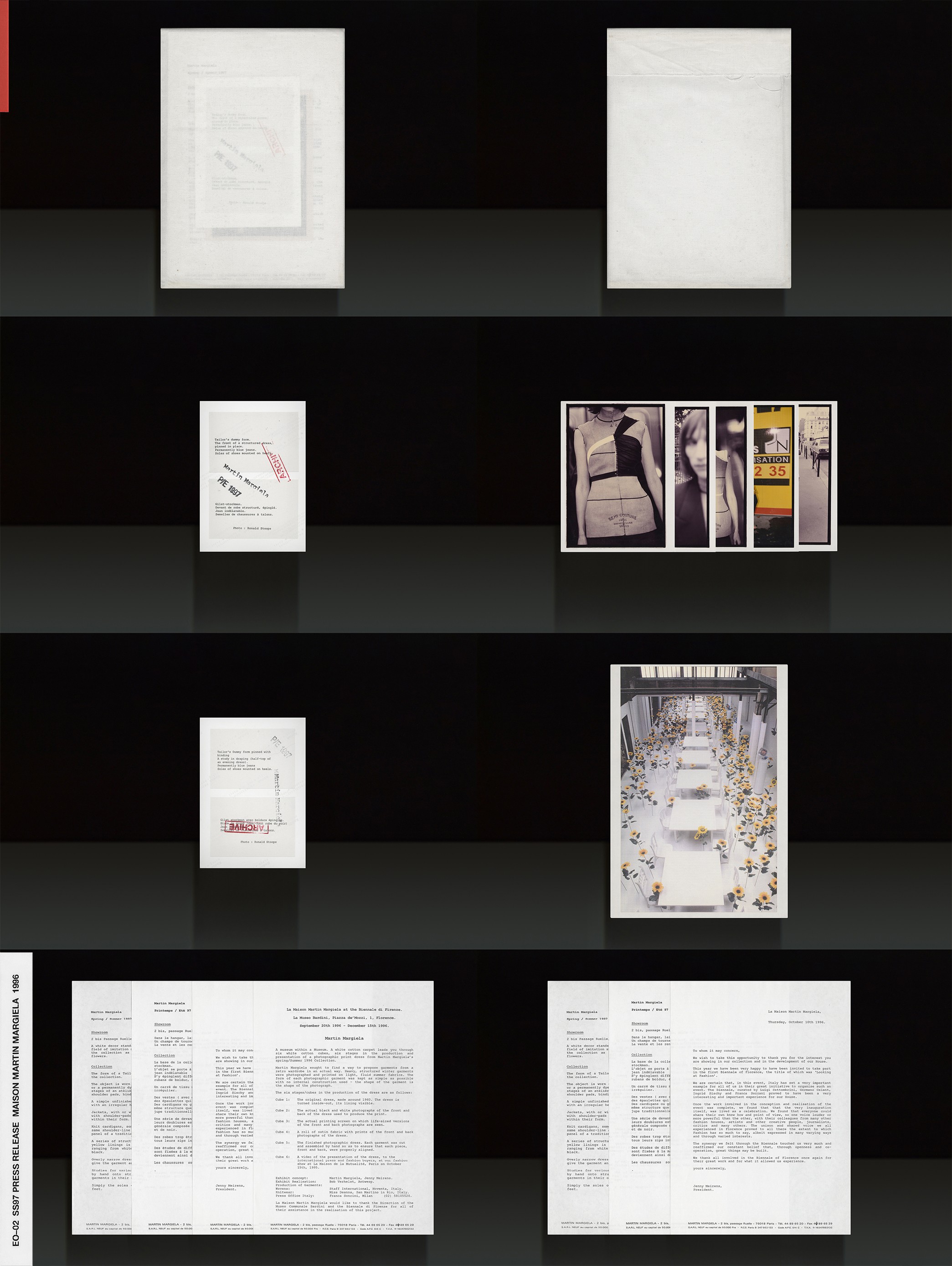

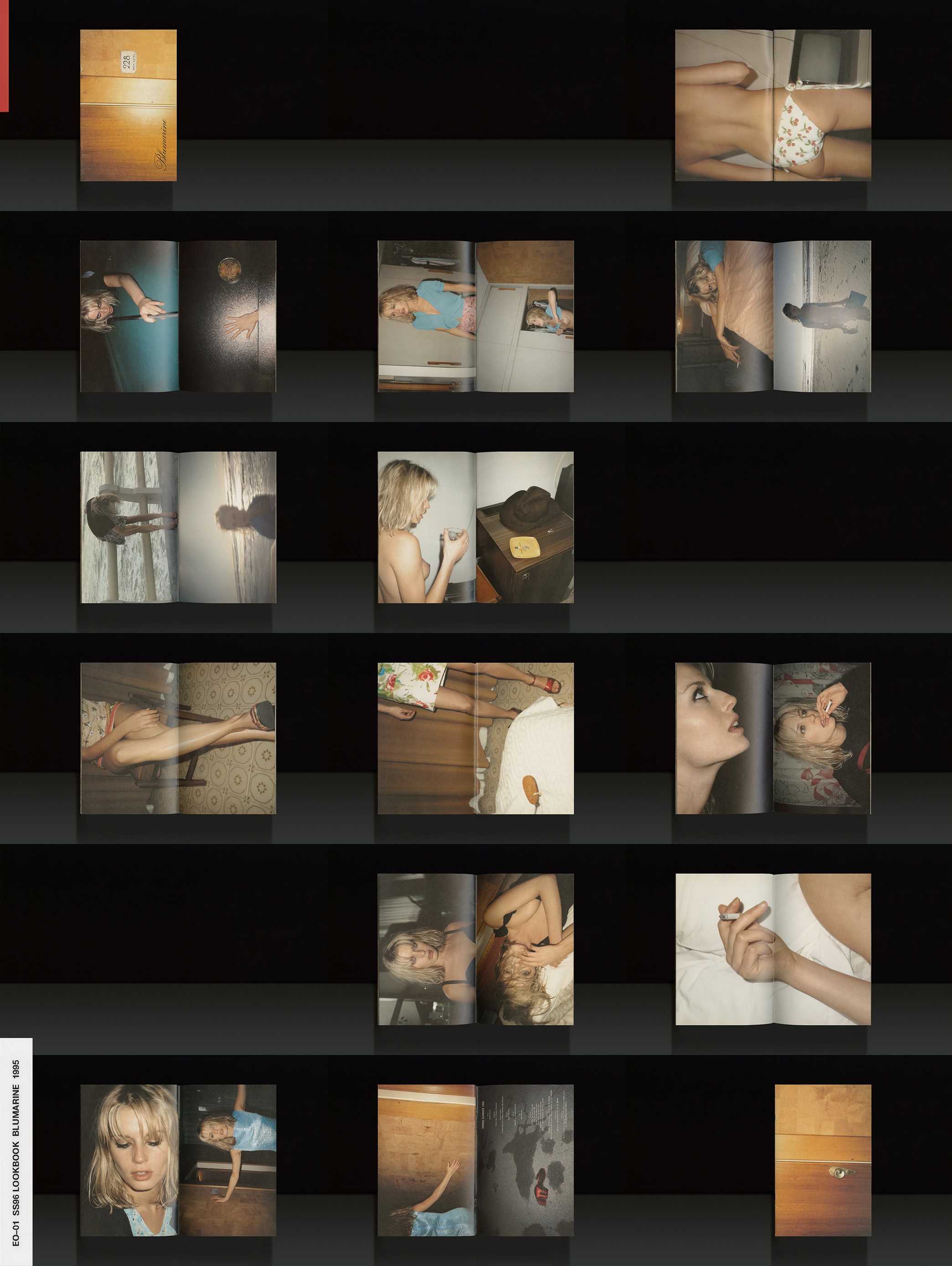

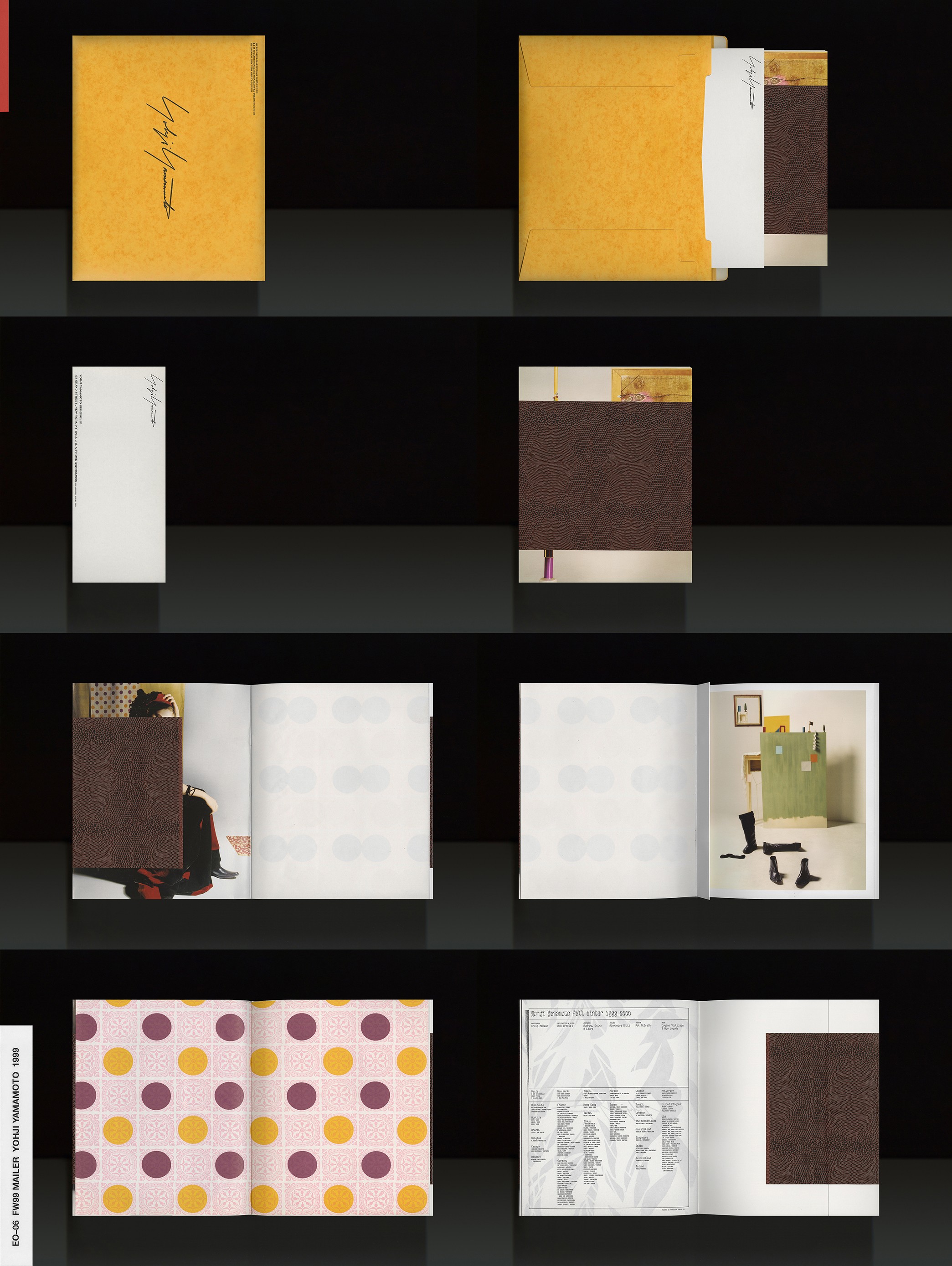

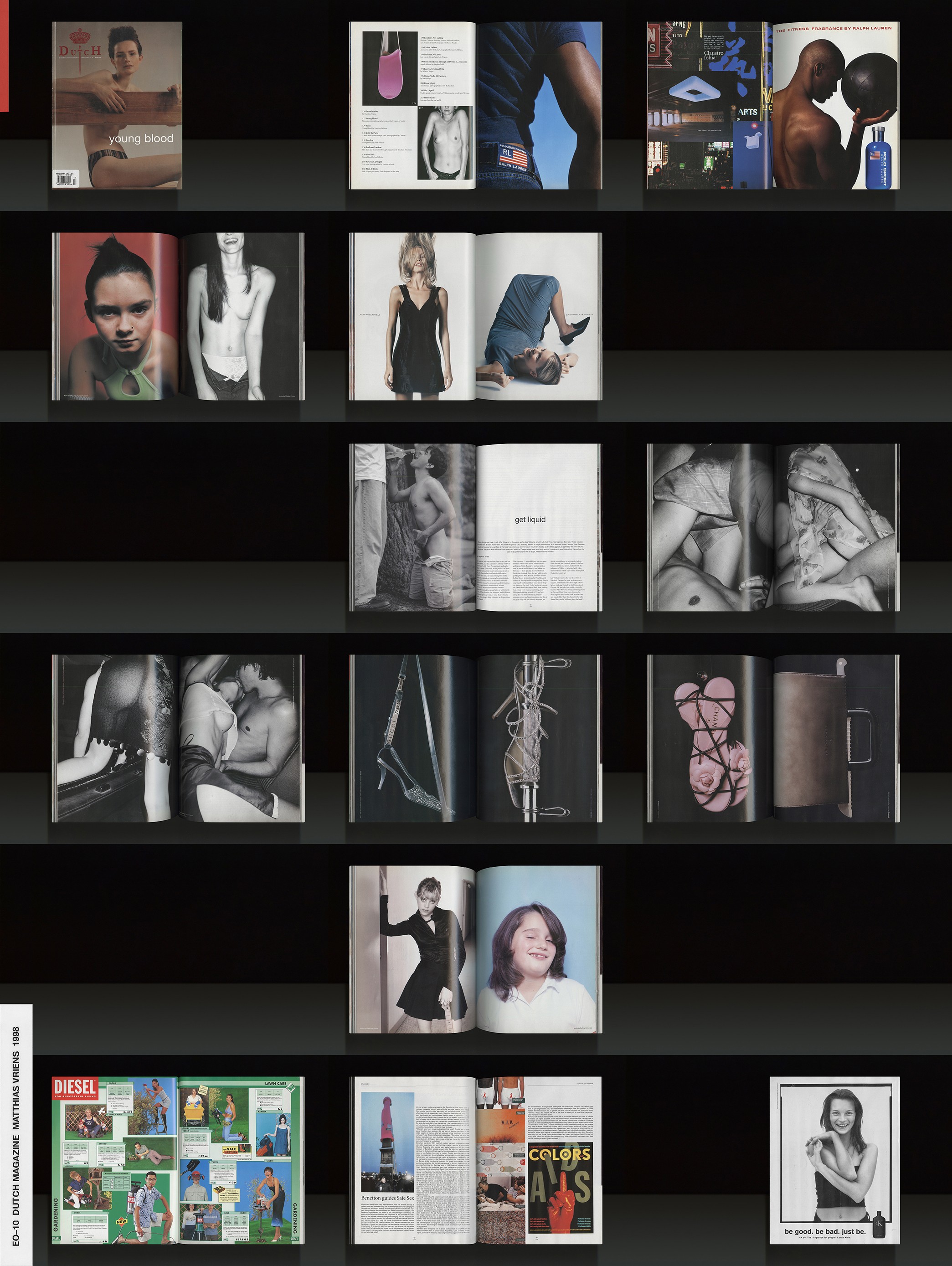

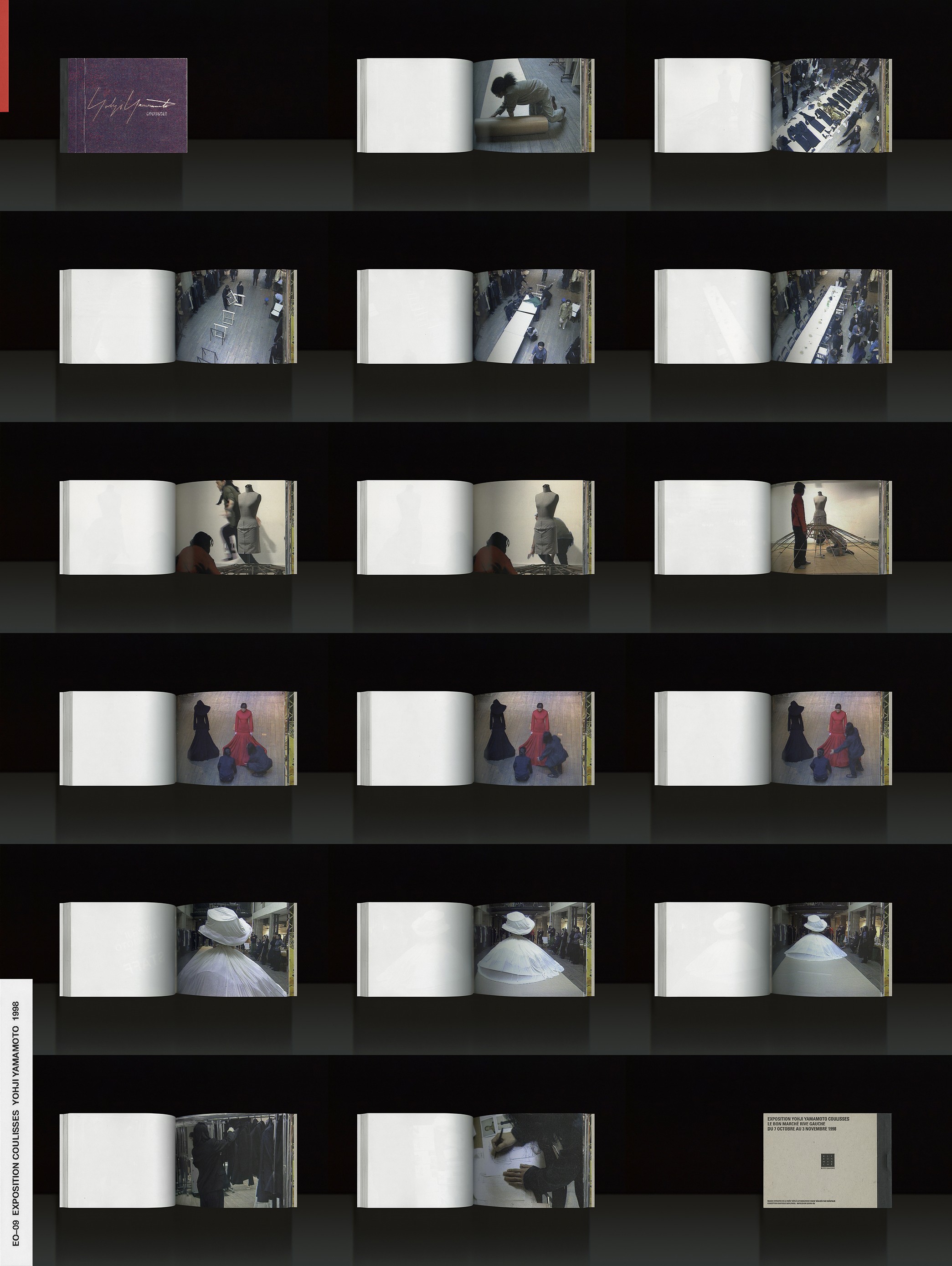

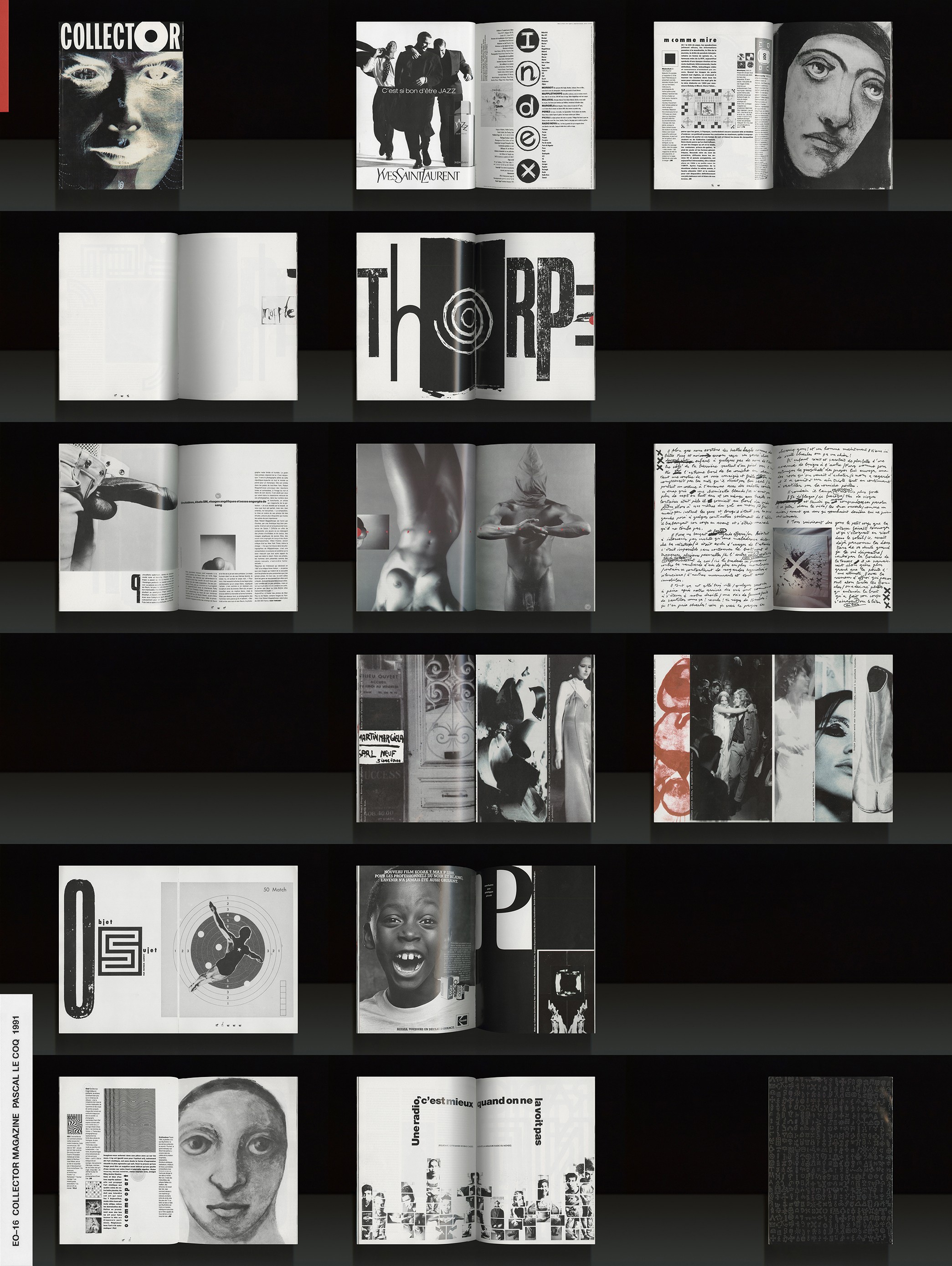

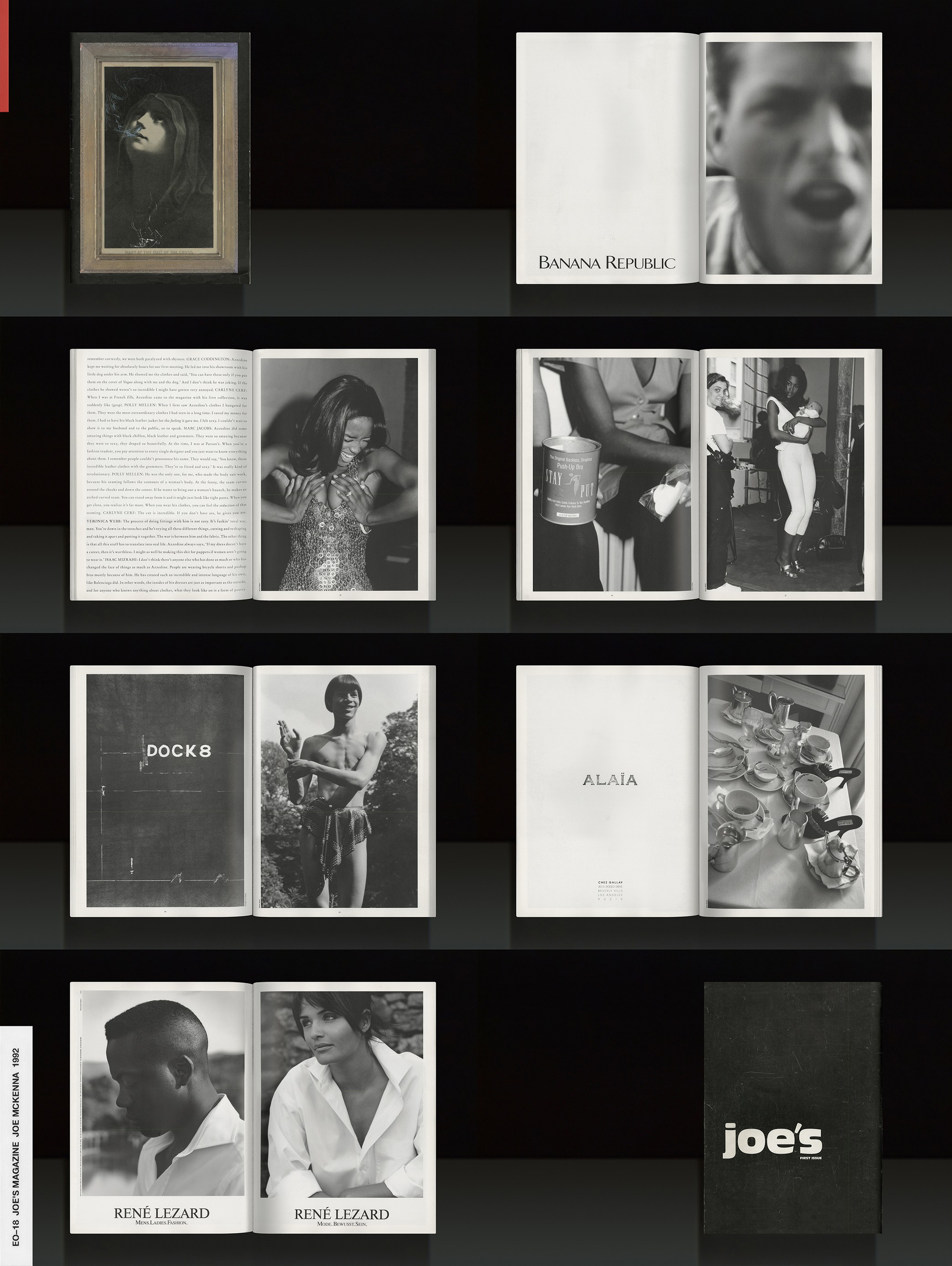

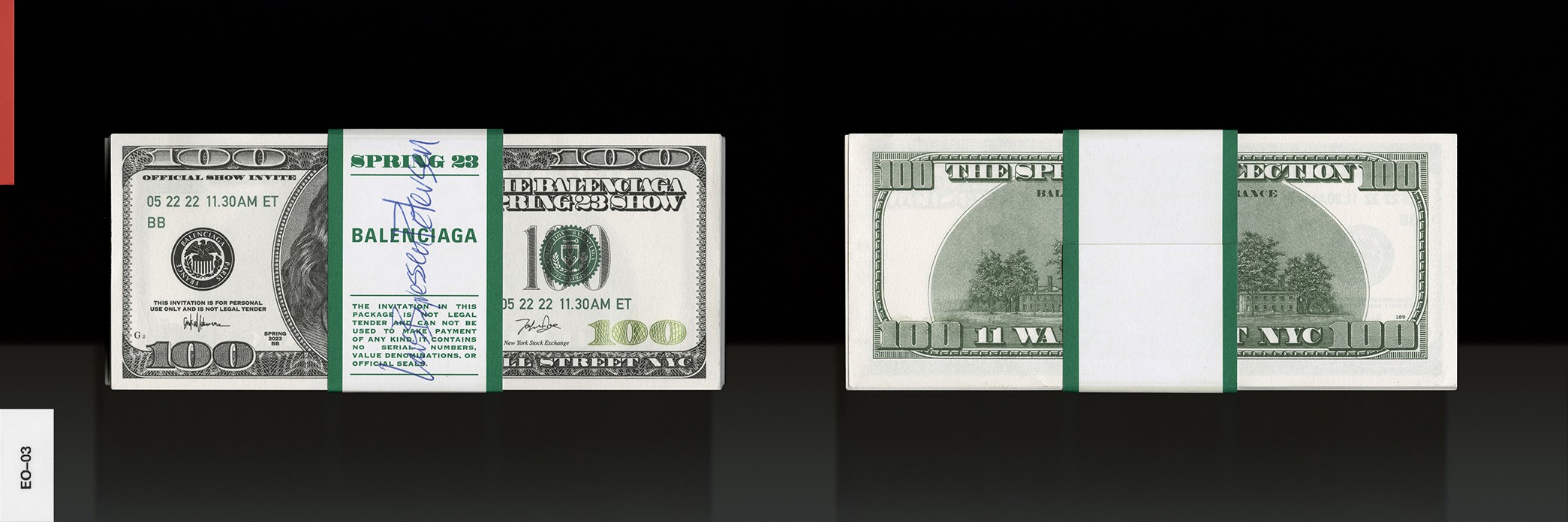

His collection barely contained any fashion books in the traditional sense. It consisted of material that mostly circulated within the industry and was not available for sale at bookstores, such as lookbooks01, press releases02, show invitations03, brand magazines04, posters, in-store sales materials05, and direct mail06 from 1975 to the present. This kind of printed matter is difficult to find after the season is over because they are largely disposable inside the industry. Typically, journalists or other press people get rid of this material after they’ve attended the shows08 and written their reviews on the collections09. And buyers and consumers typically dispose of sales materials, partly because they are free, and not considered valuable in any other way. So to acquire these materials, Steven posed as a fashion journalist, publicist or buyer. The other stuff he collected was found—on store counters to strangers' doorsteps; through which he lifted an incredibly impressive complete collection of every single .

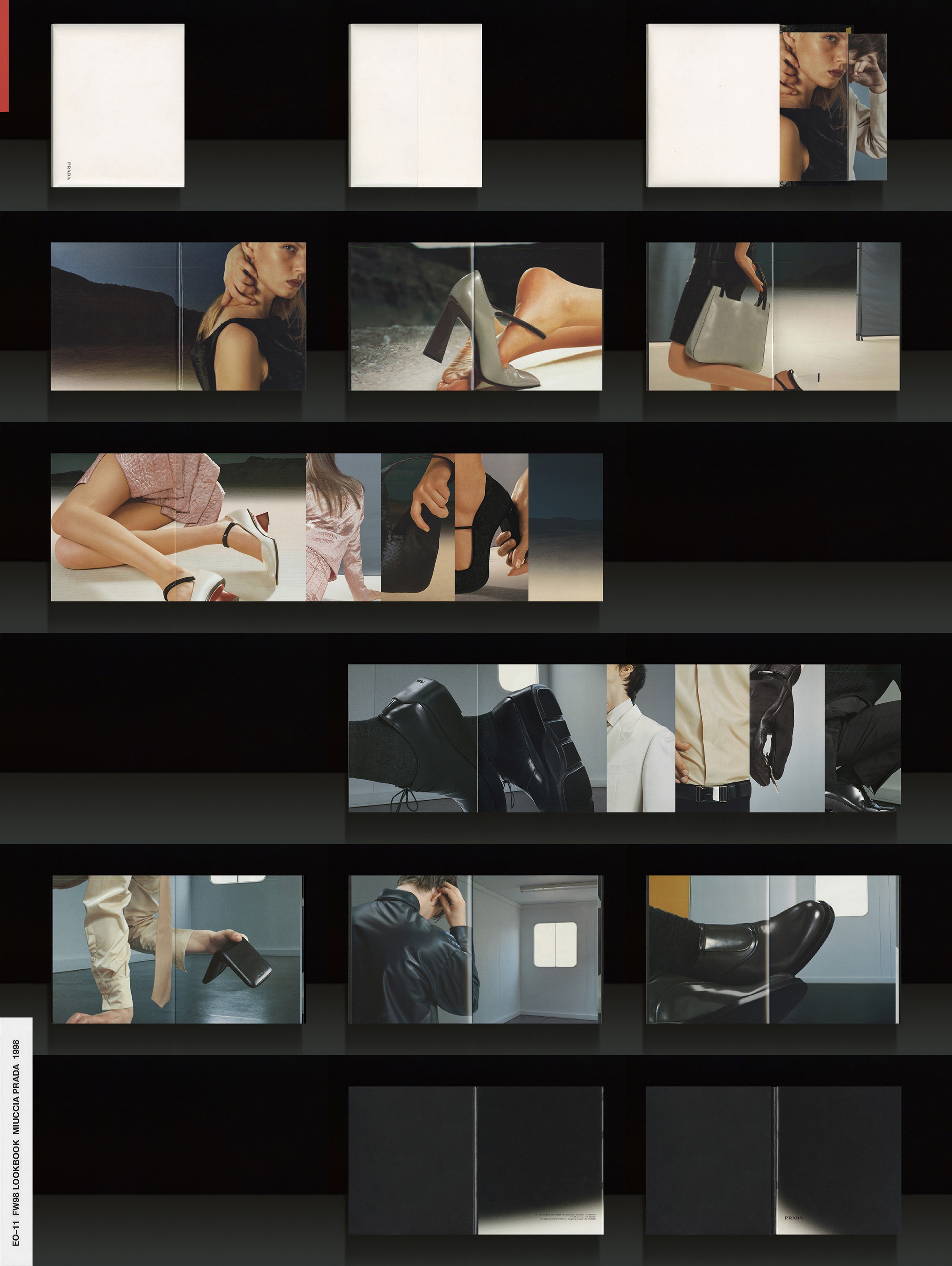

Steven’s fascination with printed matter began in the early 70s when he started collecting during the renaissance of limited edition American art books. At this time, the founders of the conceptual art movement started including the art, the exhibition, and the intellectual engagement together in a . In the early 80s he recognized that the Japanese designer Rei Kawakubo was referencing west coast conceptual art books, specifically by Ed Ruscha and Lawrence Weiner. Throughout the late 80s / early 90s Steven started collecting fashion printed matter as he noticed a handful of fashion designers’ lookbooks were evolving into a higher conceptual plane—resembling the quality of a limited edition artist book. From then on, the ethos spread and the fashion industry became flush with cash, creating all of the things we consider seminal fashion printed matter today.

Most fashion publications10 and sales materials are dismissed or ignored by collecting worlds because of their commercial purposes. For the International Library of Fashion Research’s mandate and premise, it is important to understand fashion’s history specifically through commercial material, because that's what it inherently is—commercial. Fashion’s printed matter exists to promote or sell something, creating allure or desire around products. In many ways, this is exactly what sets fashion apart from other industries and that's why I think we need to embrace it. This commercial matter is the footprint of the industry, making it a powerful tool to understand the industrial, historic and symbolic evolution of fashion.

NR

Beyond any industry, fashion pours the most resources into image making and printed matter. Why do you think this investment in visual culture is dismissed by the collecting world?

EO

Fashion isn't typically taken seriously or professionally because of this commercial or promotional element. That's also why fashion is not seen as an art form; compared to architecture, for example, because it involves some form of transaction. It has the function of buying and selling. The commercial side of fashion—pricing, where it's sold, how it's distributed—is very political when you start looking into it.

Both the collecting world and art people tend to look at fashion as perverted because of its spirituality and, partly, I would suggest, its femininity. People intellectualize how fashion promotion is manipulative by cultivating desire through bodies. But what is given less attention is the complexity of production and how technical it is. How difficult it is to make an image at the highest level, or to artistically create desirable universes that people want to buy into, in any shape or form. Whether it is hiring the best photographer, the best stylist, the best art directors, the best printing house, the best paper, the best typefaces, the best copywriters. It’s incredibly costly and it’s oftentimes incredibly ambitious. As a result, fashion publishing is home to the most sophisticated and highly produced printed matter11.

Libraries are a heavily theorized place for study. Both library spaces and its contents are usually intended for academics and experts but some are also for amateurs and enthusiasts or the wider public. Every other cultural field has libraries. But until this point we haven't really seen a dedicated fashion library. They’re always placed in relation to a costume collection in a museum, or behind closed doors in educational institutions, and it never gets the attention or dedication that it deserves.

It’s important for the study of fashion to be accessible to the wider public because there’s a perceived elitism around the field. Studying, writing and publishing are ways to take time and direct all your attention to something, and I believe in this generosity. I think culture should always be open and accessible for those who seek it. Fashion is one of the world's most universal fields—food, shelter, and clothes. Fashion is something we all relate to. Even if you chose not to care about it, that's still a form of relation. Our all-encompassing mandate and mission with the International Library of Fashion Research is to expand on cultural conversations with fashion as a point of departure.

NR

Today, as an economy, publishing verges on the impractical, sales are dwindling, is dropping, material and transportation costs are at a premium—coupled with ongoing reports of toxic work conditions and low pay at fashion magazines. All the while, factories report print runs are on a rapid rise post-pandemic, there is a historic influx of independent magazines on the newsstands, and amidst a saturated digital space the cultural real estate of print is more potent than ever.

How do you take stock of your generation’s relationship with print?

EO

I think that it's important to say that I can't speak for an entire generation, I can only speak for myself. Generally, I don't believe in the monthly magazine anymore. The magazine12 no longer functions as a source for news—the internet can serve that function better and faster. Magazines need to adapt to a modern timeframe and new ways of consuming information. Independent magazines13 are a model for this because they publish more timeless and collectible content, functioning as a luxury artifact. The key to balancing digital and physical content is to understand that the two are not competitors, but should be in sync; the real magic is in maximizing both experiences.

Print is becoming a luxury for Gen Z. Tangibility is sexy for us. From the consumer side, the statistics are very promising. Young people buy more books now than ever, although perhaps many young people have more money to spend on books now… I do think there’s a wish and a desire to create printed matter now because it possesses this different attention span. That's what drew me to the printed format in the first place. When I was a little girl, I started my publishing practice—if you can call it that—online. But I came to the realization that the internet is so saturated and I wanted to create an antidote to that digital flicker and mass consumption and exposure to information. I wanted something that was a bit more meditative and sensible. It is a luxury to sit down with something and dedicate all your attention to it, instead of having all of these distractions and all of these immediate stimulations and impulses all at once.

There’s also a hustler element… I wanted to make my own money. I wanted to feel the adrenaline, the pace, the pressure. From my experience, it’s hard to get taken seriously, or professionally, when you’re younger. Because of my age, I have been rejected for funds or grants tons of times, photographers have refused to work with me, I even had to use a fake ID to get into my own magazine launch parties. Plus, other established and commercial magazines like to hold their power over you, simply because you “haven’t paid your dues”... I believe all of these actions are made in fear of the young generation taking over the industry. These aspects are the hardest part of the game. But, frustration fuels my motivation and creativity. When I'm in a good head space, or even financially à jour, I’m not necessarily the best creator.

NR

Were there sources that guided you through the process and decision to start an institution?

EO

A few years ago I read A Short Life of Trouble14 by , this was before I was offered the collection from Steven. Marcia Tucker was incredibly brave and full of courage. In the beginning, put on guerilla exhibitions and small activities—that you would usually see in a ‘janky’ project space. The fact that they raised funds and chose to carry out these projects in an institutionalized framework made it radical. Just because of this change of display, the programming was considered differently. I think that she had that same mentality that I had with my publishing and with the International Library of Fashion Research. I’m sure it would have been easier to establish the library in a smaller scale space, or to call it something else than a library and by that defy a library’s requirements, but I had this wish to solidify it in an institutional context, I guess to underline its official-ness or legitimacy. Call me naive. Marcia Tucker’s work got me thinking about what an institution, such as a library, of the 21st century is, or can be, and how it can potentially be done differently.

Through the International Library of Fashion Research I’m working with the , which is a huge governmental institution with hundreds of employees. When I feel drained from that experience, I try to think about what Marcia did—how she too was elbowing her way through the bureaucracy or established walls. It has to do with wanting to see a particular space in the world, and creating it. Marcia took a huge financial and career risk—although she was at a different age when she did these things, she remained in that space of naivety and childishness of just doing it and jumping into it, and then sort of finding her way as she went. If I had this library I’m now running in my hometown when I started out, it would have made a big difference for me. So I went about and created it.

Marcia didn't necessarily have the experience that it took. I definitely don't, I don't have a formal education. I don't really know what it takes for these things to operate and run. When the container of Steven's collection landed, after being transported on a boat from New York to Oslo, you know, it sort of slammed at the dock at the harbor. And I was like, what the fuck have I just done? I can’t just get rid of this if my plan doesn’t work out. What her memoir showed is that you can do so much with experience, but it has to do with the will of learning, and folding up your sleeves and getting to the work, and of course, a vision.

NR

At such an early age, what compelled you to start a publishing practice?

EO

You would have to go far back to track it down…I feel that my practice started when I was a child in Oslo and had these traits that are now kind of vanishing because of the overall responsibilities of growing up. And I'm trying to really hold onto it, but this curiosity and naivety, especially in writing, is where everything started.

Text has always been my medium. That's where I've expressed myself best. I didn't start out as very visual. I couldn't really draw, I couldn't paint, I wasn’t crafty, I didn’t have a steady hand, I wasn’t a perfectionist at all. I used to love reading the newspaper. At 8 or 9 I wrote a 120 page fiction book in a Word document on my —which shut down, and I haven't been able to access it since. In my public school library, I sought stuff that wasn't really meant for my own demographic. I was supposed to read children's books about girly things and horses or whatever but I wanted literature to be something that I was aspiring to. I wanted it to be ambitious.

After that, one of my first impulses was to blog. I started my own blog on when I was 8, which was a very common thing to do at that time. This was before Instagram. The blog was in Norwegian at first and I would write about, like, who I was hanging out with in the school yard, what I'd eat in my lunchbox at school—you know, incredibly flat. Then it kind of evolved into being more sort of like a fashion blog but fashion in the sense that I was posting outfit photos and this was very much in tandem with — do you remember that site? I was living in the suburbs of Oslo and didn't feel that I had any peers here who I could share my interests with. It was online where I really found a diverse group of people that I could relate and speak to—Internet friends who to this day I have not yet met.

NR

At age 13 you started —becoming the youngest magazine editor in the world. Recens was published across seven issues and featured contributions from over 500 young people from all around the world. The bourgeoning perspective of Recens challenged the fashion industries stance on beauty standards, gender stereotypes, and commercialism.

How has the development of your personal library impacted your early work?

EO

I think it's important to mention that I don't really relate to that whole age aspect anymore, or that I was starting out young or whatever. That's been so for me. It's always kind of been milked or used as a marketing thing, whether consciously or unconsciously from my side. At some point it was just taken out of my hands…

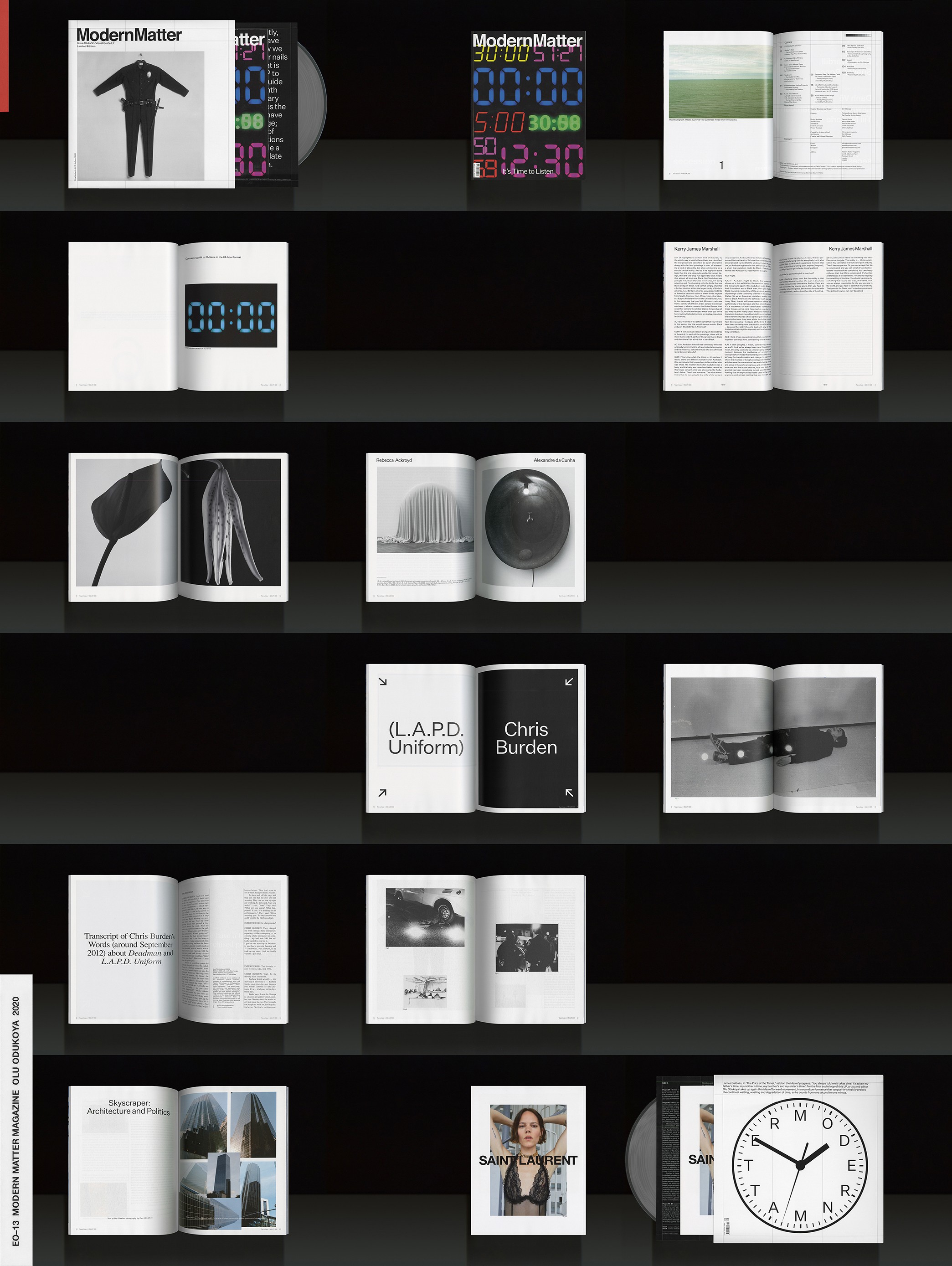

I started collecting the minute I bought my first magazine. I would be nothing without this collection. I don't have any formal education, all of these magazines and books are my education. This is my research. I've spent a lot of money on this collection—but probably not more than what it would cost for school tuition or studying anything creative. I managed to specialize within print publishing because I've seen a lot of printed objects and printed matter.

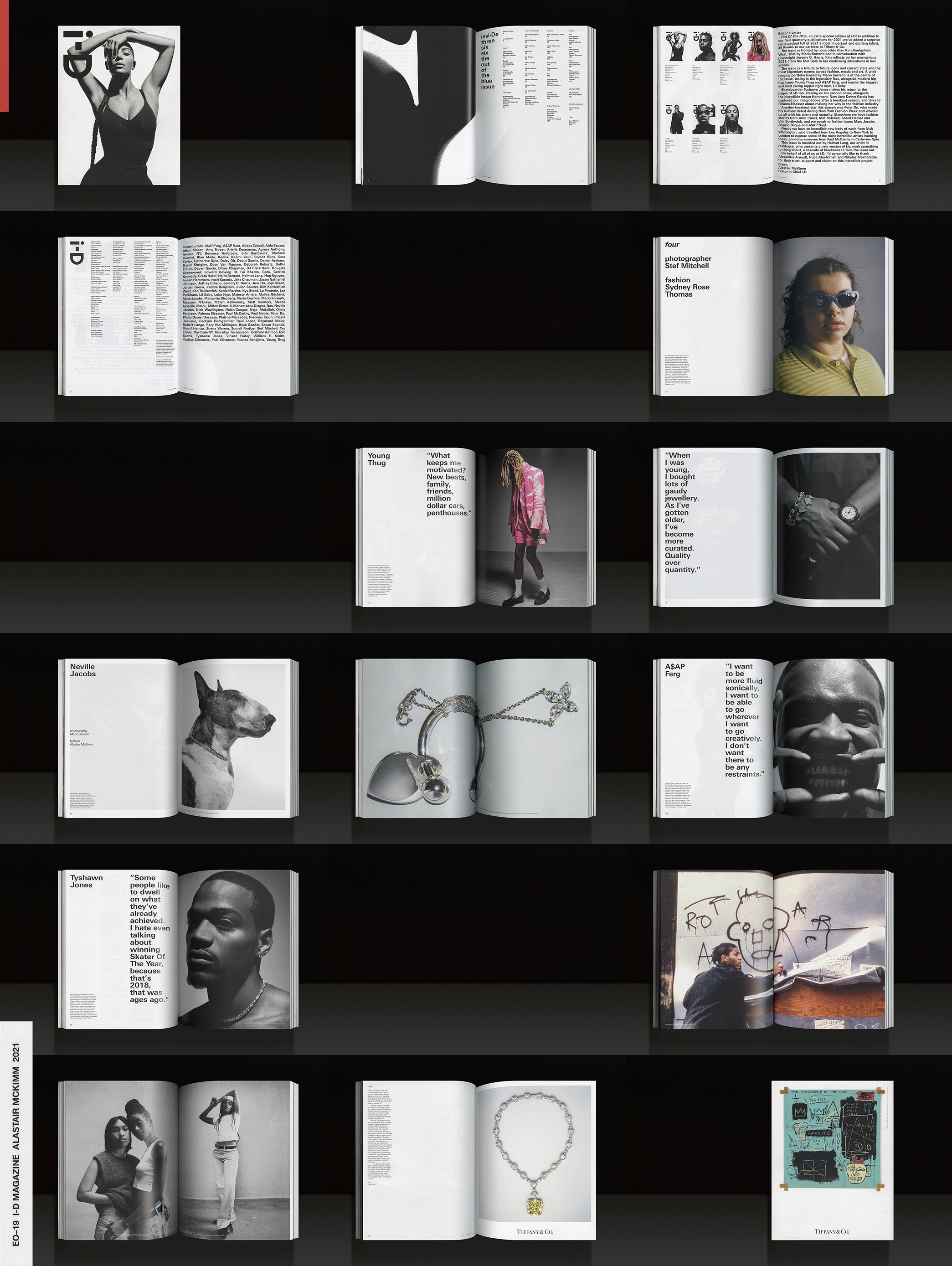

I don't really buy magazines anymore. My interest faded. My magazine collection is of a very specific time period—I kind of stopped actively collecting when I started producing my own publications because it's so costly to produce your own magazines that I couldn't really afford buying anything else. So, my collection consists of i-D magazine up until a very specific point, Dazed up until a specific point, early Kaleidoscope, early Novembre magazine, very early 032c Magazine15. I also stopped buying a lot of these publications because they became completely saturated. I stopped taking interest in them. It's as simple as that.

My magazine collection represents a time when I was hungry for all these impulses and really obsessed with the field, because I wasn’t actively part of the ‘scene’ myself. This is not to say that stuff was better in the past or whatever. At this point I started making stuff myself that was in opposition to everything else that was out there, and I quickly felt full. I had to be careful with how much I looked at, because it was easy to feel saturated or exhausted... And I saw so many people that I was really intimidated by and also heavily questioned.

NR

What were you intimidated by?

EO

People with a lot of power; the politics and money of the fashion industry is just incredible. As a young person, it was kind of hard to understand how influential, and big, and nasty the industry is. That's not just talking about ethics and production, but the fact that the power of the industry is in control of a very select group—you can name them on two hands, basically. These are the people who have the operational, financial, and symbolic power to actually execute big change if they want to. They chew you, and then spit you out again. It's a bit like politics in society at large. And when you start fucking with these people you're at risk of jeopardizing your own career. Being a young person I think that a lot of people feel a little bit threatened and that's a risky position to be in. So, I started feeling really intimidated by these people, and my naive way of dealing with that was to confront these people. And that's how , my second magazine project, came to be.

NR

Your second magazine, Wallet, investigates Fashion as a political system—critically examining the pressing issues of the industry and how it operates through different mechanisms (individuals, money, politics, power, press, technology, and education).

What can we learn about fashion’s infrastructure by looking at who creates and participates in fashion printed matter?

EO

A lot of people ask me, now that the print is “dying”, what is the magazine's function? When you really strip it down and look at the essence of a magazine, it is a time capsule. It is still the only product in the whole industry where you can stop time and put all your attention into something and breathe in the middle of this very accelerated industry, right? You can never stop time with a collection. A magazine is an artifact that you can use to look at a moment in time to understand what's happening right now, or 25 years ago.. Who shot the cover? Who did the product photos? Who did the writing? Who was the editor-in-chief back then? There's a track record of who is participating, and examining this reveals the infrastructure of the industry and how it operates.

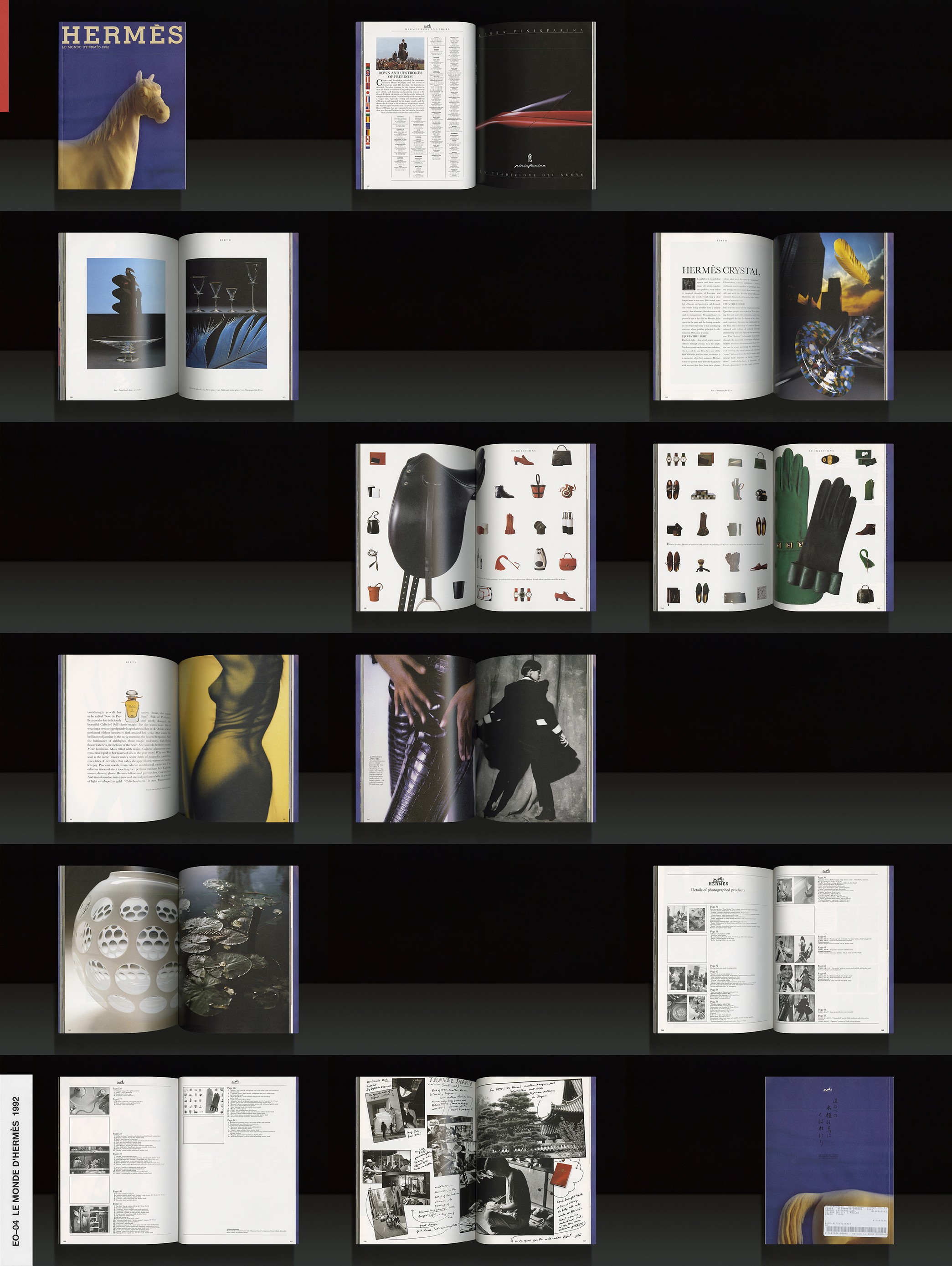

And you know, I've always said it, fashion is one big circle jerk—and please quote me on that. I've come to realize this further through tracking down the library collection which now spans from 1975 until the present. It has been the same people working across all the different brands or publications—the same photographers, stylists, copywriters... everything is the same. And it still is. Maybe this is also why I stopped collecting magazines. Yes it's a circulation, they're being switched out a little bit, but again, it's the same five or six, predominantly white and male, photographers that are doing a Loewe catalog, a Marni catalog and also a Louis Vuitton catalog, but then also shooting the cover of i-D and System Magazine. There are political structures within that too. If you shoot i-D, obviously you can’t shoot Dazed. If you shoot Vogue and L'Officiel then you can’t shoot Numèro or Harper’s Bazaar. There’s contracts for this kind of shit, because of competition and loyalty, and so on. Let’s stir it up!

Fashion is a global industry today so it's easy to become a part of a subculture. But at the same time, subcultures are no longer small or niche. Everything is out there and everything is global and has the potential of going mainstream. It's easy to find peers, internet friends, and like-minded people online. That has also influenced the way that fashion and fashion publishing operates—independent fashion publishing used to represent a certain niche16 or a certain subculture17. But now, it's all very fluid. I find this dichotomy between the “broad” and the niche very interesting, and I will continue to challenge this through my work in publishing and with the library.

NR

How has the flattening of subcultures and consolidation of power impacted the content of these publications?

EO

This is when stuff becomes incredibly bland and you feel like you've seen it all because it's the same selected people who get to speak and express themselves and there's no space for anyone else. A lot of it is in the hands of agents—most of these people come from the same three agencies; , , or . I don't know if they do it because it's convenient, or they ultimately like their style or expression, or because there's a certain power dynamic here that we don't really see on the surface. But this is what it is. Saying these things out loud will probably single-handedly make me broke for the rest of my life.

The reason why there are the same few people and why the power is so consolidated and saturated is because of finances. Back in the day, it was cheaper and easier to print something, so more people would do it. There was a magazine for every subculture or theme, more diversity, a wider span and spectrum. This is why in my personal collection there are a lot of first issues18. The first issue is the hardest one to make, it’s a spectacle, it’s incredibly special, and often it’s so pricey to do one that they blow their budgets already, or there is so much pressure leading up the next editions that they discontinue.

NR

For the people who want to start a magazine, could you provide transparency really down to the nuts and bolts—how much does it cost to make a magazine? How much can you expect to make from ads and sales? What kind of staff do you need?

EO

My biggest advice is don't ever go into publishing if you want to make money. It's not, and can’t be, a money-making thing. If you look at brands these days, when they make a magazine, catalog, or any sort of printed matter it always goes out of the communications budget and it's considered an expense.

When it comes to an independent magazine—there are so many variables—but I can speak from Recens’ and Wallet’s perspective. Recens was in a standard magazine size, 21 by 28 centimeters, and 150 pages roughly. It cost $8,000 to print 1,300 copies in 2015. By the way, $8,000 is before taxes and shipping and everything else. The costs never end up being what you estimate. I remember once we had an advertising partnership with Adidas and they took half a year to pay, which is fucked up. I was 16 years old and had to write this letter to the director of Adidas and be incredibly firm. “If we don’t hear from you within today’s end, I will pass this to our legal department” and then I would CC, like, legal@recenspaper.com. Obviously we didn’t have a legal department but it’s a very good tip because then people are actually shit scared, so they came right back and paid.

Wallet is a very small publication, the format is 11 by 22 centimeters, and only 60 pages total. It costs about $3,000 to print in a circulation of 2,000 copies. So, it's pretty cheap. With advertising it varies a little bit, but we make $6,000. We have a small team—myself and my business partner are not taking any salary from this because it has been our journalistic platform and a portfolio for us. It's an investment. Everything goes back into the company. We have two other contributing editors that we've offered a small symbolic fee, and a copy editor for proof checking. And then there’s accounting fees and costs that it takes to just even run a company, shipping, and then there’s distribution...

I have a surreal passion for distribution. I love the distribution process and everyone thinks that I'm crazy for saying that. One of the most important things is getting it out to the people. It’s also such a closed part of the process. At the same time, distribution is not where the money is. Your income needs to potentially come from either ads or other parts of the cycle, because distribution is such a corrupt system—there's so much scamming and that's what nobody is really speaking on, I guess that's why it's being allowed to continue.

NR

Go on…

EO

We work with a bunch of different distributors and there’s this big one that basically gets all the magazines into the mainstream news stands (e.g. all newsstands in New York to popular in Sweden are all handled by this one distributor). Typically when you work with a distributor they take 60% off of every copy sold, but you never receive proof of how many copies are sold. Their sales report comes back six months after the issue is finished running. So, say the report says that they've sold a hundred copies and we sent them 900 copies. I have no idea if they've actually sold a hundred copies.

Every publisher really knows about this [poor sales reports], but nobody can do anything about it because you have no proof. There have been times where I've had proof as well, for example, I went to in Berlin and I saw issue three of Recens Paper still selling. And that was published in 2014—we got the sales report six years ago, and then it’s supposed to be recycled or taken out of the loop. Yet they're still selling it. Back in the day, there used to be a return policy that you would receive back the issues that weren't sold so you would have proof of how many actually sold. But they don't operate like that anymore because it’s too costly and would involve too much logistics. Things are so global they know that it’s easy to take advantage of independent publishers.

That's why a lot of independent publishers are dealing with distribution themselves and selling on commission by working with select retail stores and invoicing upon delivery—they have to pay upfront. But still, you don't make much. If we're supposed to do a 50-50 cut and I sell you 10 magazines for $6 plus shipping and you sell them for $12—we're not talking big money.

This is the ugly duck in publishing. How do we go about tackling these challenges as individual publishers? I'm not saying we necessarily need to rescue all of these publications because I really don't think that everything needs to be rescued. Especially the hyper commercial magazines that have no relevance anymore. I think that there are definitely ways. There are new models; one of them is called New Distribution House in New York, Motto Books in Germany, KD Presse in Paris and there's also Antenne Books in the UK. But essentially, they make their money on books, and that's what they prefer to distribute. Or, if you look at brands such as Gucci and Prada who've been two of Wallet’s main advertisers for a long time, their strategy is to not necessarily place one ad in Vogue, but they would rather place 10 different ads and in 10 different independent smaller magazines to support that industry. I think that sponsorship/donation based culture is very important and admirable.

NR

Are you optimistic?

EO

Very optimistic. I'm optimistic because these challenges are what excites me. I'm trying to solve a lot of these questions, you know, all my publishing projects are sort of an attempt of doing that. Grappling with challenges is why I’m in this, ultimately. I think the biggest challenge for me would be to take on a big commercial title to see if I could make people buy and read it. And I'm not shy about the commerciality either—I just think that we need to be very conscious of it, acknowledge it and talk about it.

Lately I've personally been buying magazines and other printed matter again and honestly, fashion has been incredibly stale for the past four years and the magazines were a reflection of that. I think something’s starting to happen again. It’s a pendulum effect. Maybe not visually speaking but there’s institutional moves happening that I find to be interesting to question and read about.

I recently bought the new i-D19 the special issue they did with Tiffany's. I thought that was brilliant. The journalism is typical i-D but the way they created this full on advertorial magazine, blatantly commercial, that's 250 or 300 pages, is super interesting. It is also filled with an interesting mix of people like wearing beautifully styled diamond chains and pearls. It's so simple, yet it’s probably a million dollar project, although low res with analog photography. The issue is powerful because it really marks a big change. This says that the advertising world is so rotten that they have to come up with this entire new way of creating content with commercial interest.

NR

You’ve said that “education is completely irrelevant…because kids already know where to get their Information. The internet created a different understanding of the world.”

Before dropping out of highschool at 16 to work full-time, your schedule consisted of school from 8am until 3pm then after school, going to your office space in Central Oslo to serve as a magazine editor. What has formed your knowledge on publishing and making books?

EO

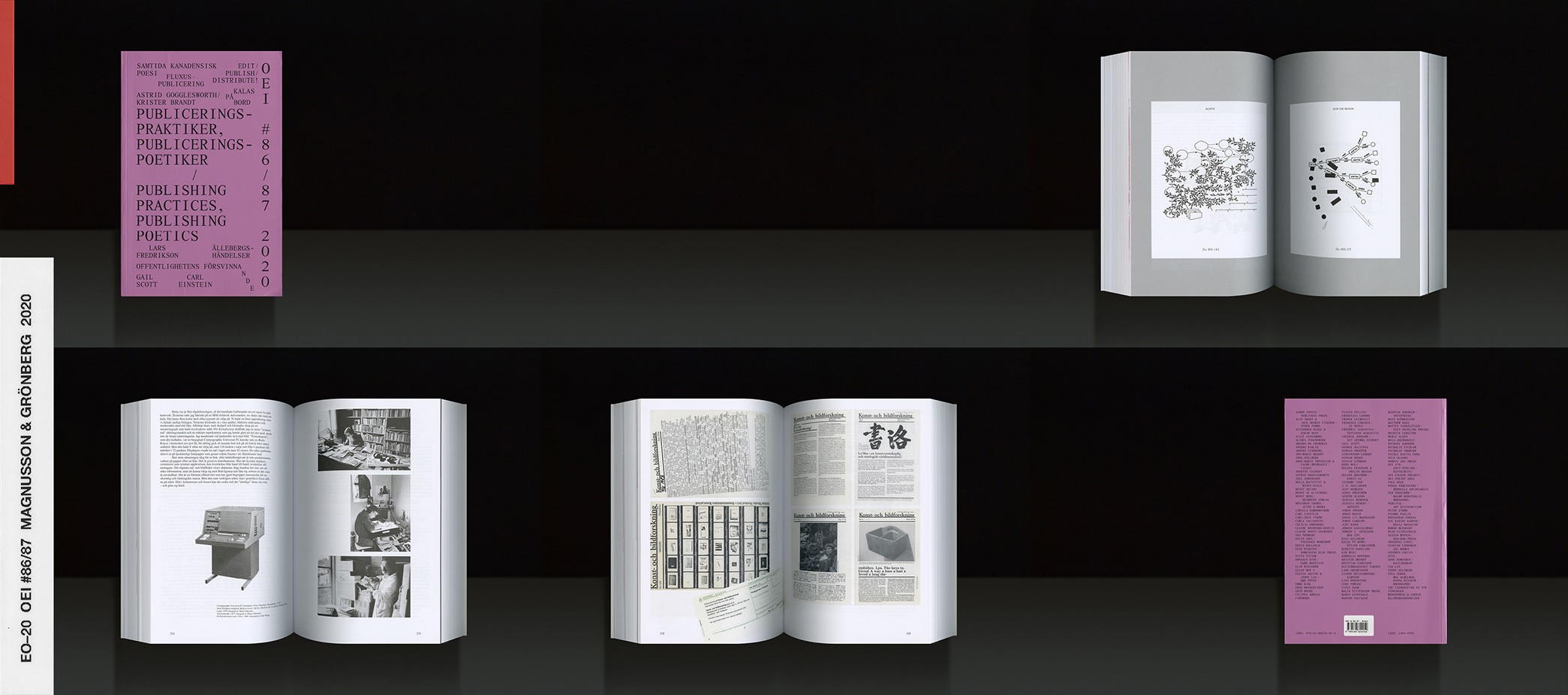

I think OEI20 is incredible. I don’t know if they’re well known outside of Scandinavia but through their publishing house they’ve done some very influential theme-specific issues around experimental writing. They host conferences and one of their editions is ‘Publishing Practices, Publishing Poetics’ which kind of outlines various different publishing forms or structures, from genres of literature to comics. It’s very rigorous. The book No ISBN21 outlines the entire contemporary publishing eco-system or cycle by withdrawing from the wider system of publishing. The book features 1,800 publications; from cheaply printed flyers to handmade or hand-bound editions, circulating without an ISBN, so consequently they’re looked upon as ‘unofficial’ works, which is very interesting, that it’s the ISBN number that ‘legitimizes’ them.

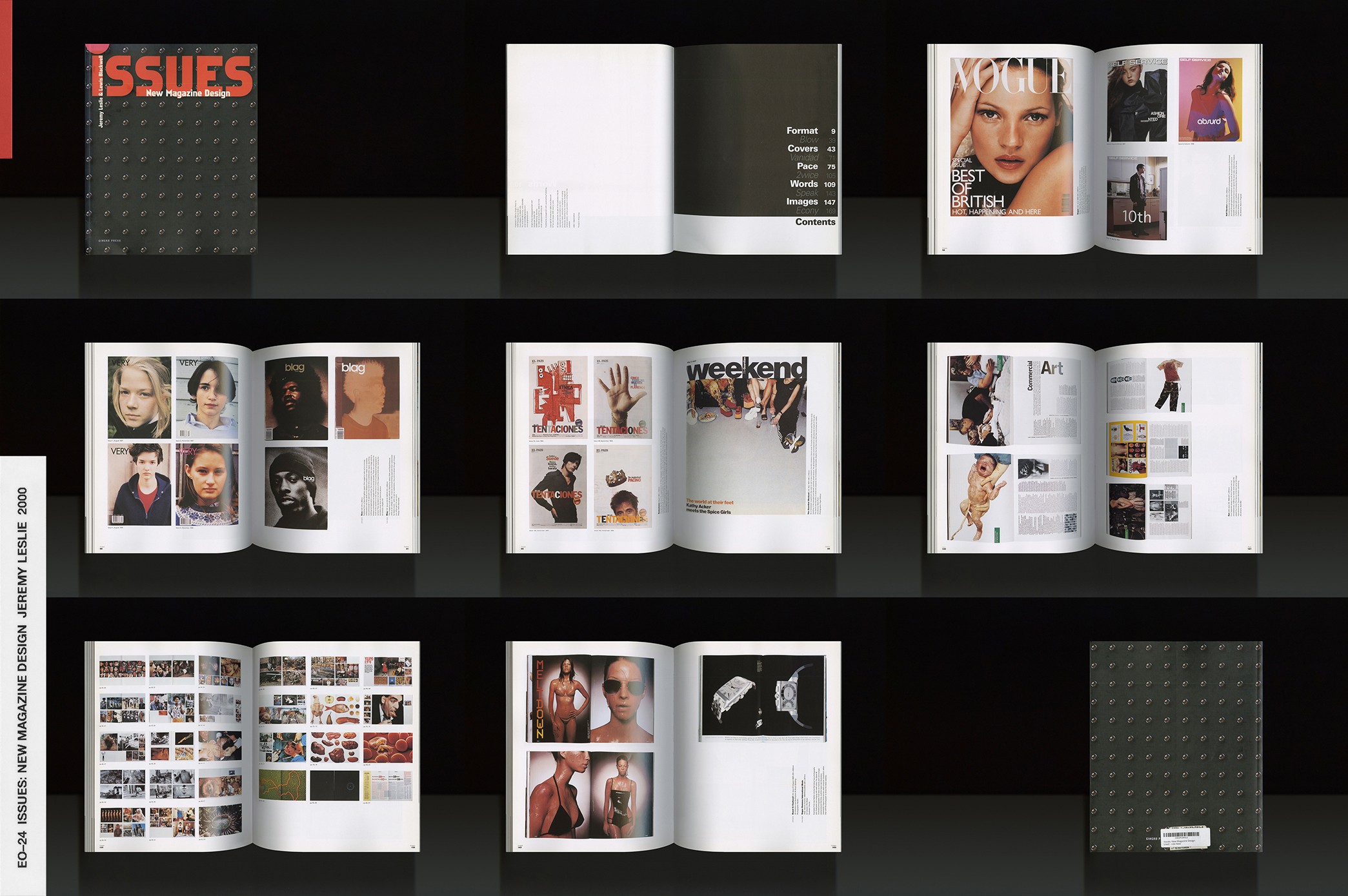

BookTrek22 Selected Essays on Artists’ Books is also interesting. It’s been a long time since I read this one. I got Issues: Issues: New Magazine Design23 at a flea market. It's incredible. The author, Jeremy Leslie runs the magazine store magCulture in London and has done so much writing24 and thinking in the magazine field. And then Issues25 by Vince Aletti who I’ve been fortunate enough to get to know personally which has been an incredible honor. Oh yeah and also, Self Publish, Be Happy26 by Bruno Ceschel who also is an incredible contributor to conceptualizing or theorizing ‘the magazine’.

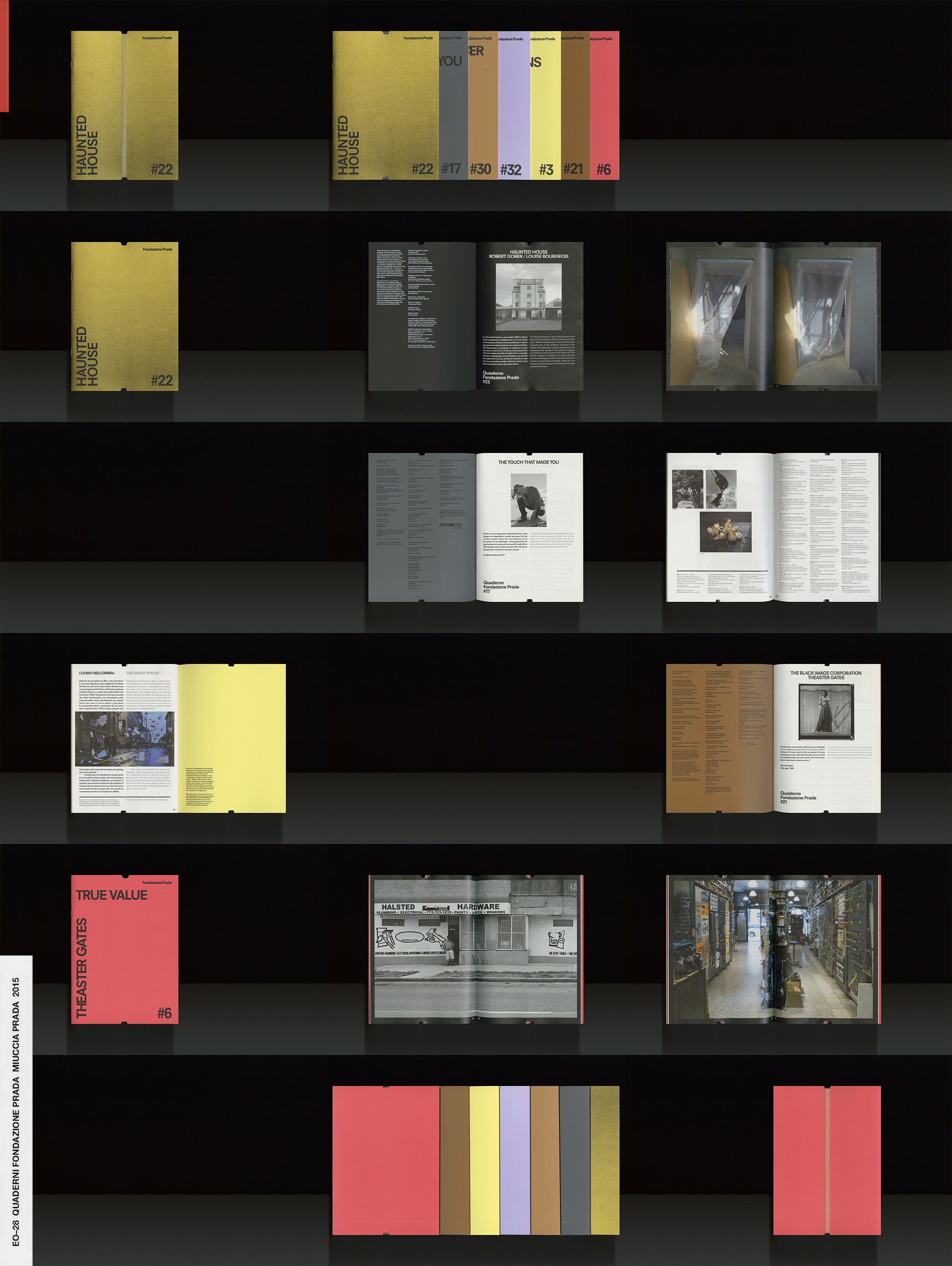

I also draw a lot of inspiration from the French cartoon Mœbius27, the idea of using different frames is a very unique way to direct or narrate a story. This idea is also something that has parallels to an artistic practice. As an artist, you decide when a work is finished and is ready to be out there, or when you're discontinuing something you've been working on as a body of work. One can have that control of how they want their projects to live on, and create certain myths around stuff. I think that artists28 sort of allow themselves to speak on these things more than I could as a publisher, which puts their publishing projects on a different pedestal. Both Richard Prince29 and Ed Ruscha30 who are prominent artists using book-making and publishing in their art practices in an inspiring way.

NR

As you exited the classroom, what did going outside to pursue independent publishing teach you?

EO

Meeting with other humans is where my biggest learning curve has been as well as the motivation of so much of my past work. For example, when I wanted to speak with the CEO of Comme Des Garcons () back when I was a completely unknown writer I reached out to him by taking a guess at his personal Gmail account by trying different email addresses just to see which one worked. And one day it came through and happened. We forget that this is such a human industry. This is about people and people expressing themselves.

There's so much power in saying no. That's a very important lesson for young people. It's better to say no one time too many, than to say yes all the time. As young people manifesting themselves into this space one can be happy for every opportunity, you're just extremely grateful because you don't think you're ever going to be asked for something ever again. So you say yes to all these different things and you learn that, you know, sometimes it's incredibly important to say no, and put your foot down and set boundaries. You can get all the advice that you'd like but at the end of the day make your own decisions and you make your own choices and you protect your own intentions.

Intuition is key. For example, I went to Tokyo for 10 days by myself when I was 15 and the only thing I had to trust was my gut feeling. That’s what keeps you company, an anchor in yourself. And I feel that by making publications and doing all of these projects, I can be very much in my own head and it can be really lonely even though there’s a team. That’s when I seek comfort in my intuition.

Also, the method of trial and error. Don't shy away from making mistakes. Amplify them, rather, or acknowledge and appreciate them a little bit too. I think that making mistakes is just learning in its essence. That's what happened with the first issue of Recens Paper. It came out from print with typos, it was and it was awful. There was just so much naivety to it and it goes back to the power of that childish mentality that I really hope to maintain for the rest of my life.

If I could give advice to myself back then, I’d say to go even harder. You have nothing to lose. Now I’m 21 and I can’t hide behind my youth anymore. Back then it was the only thing to do—get up and out. A lot of people ask me if I’ve ever felt like I grew up too fast or missed out on my youth. Honestly, I don’t know the alternative. I feel like I’ve had a great childhood and teenage years. I’ve seen parts of the world at a very young age, met amazing people and had incredible conversations. That’s fun to me. I’ve chosen it, you know? And if I wanted something else, I would have chosen otherwise.

NR

What books would you recommend to the next generation seeking to get into the fashion industry?

EO

Sport and Meditation: The Inner Dimension of Sport31 by . It’s not necessarily spoken about in culture or in fashion or as an artist, but everything comes down to performance enhancement. Everyone's trying to perform at their best, and when you work in such an accelerated industry one deals with all of the external and internal pressures and expectations.

When I took the leap of quitting school and deciding to break out into publishing, my livelihood became dependent on going all in. I had to be fully invested. This is something that all athletes need to deal with at some point ‘going pro’, it’s just that in culture or creative industries there is no support system or structure for this moment or shift, there’s no safety net, no training facilities. You’re on your own.

I'm a big sports fan. Ultimately, what I like about sport, I guess outside of the entertainment element, is the idea of pushing yourself to your maximum level. That you can be growing, learning and exercising always. I think that that's the same with creativity, it's an exercise, you need to wake up every day and stimulate yourself with different things and you need to see stuff but not too much stuff. The balance between work and restitution is very important because in order to be at your best, you have to take care of yourself and rest. We don't really let ourselves have that time off. It's unheard of in fashion.

I've also read both of the memoirs32 by . She speaks a lot about having to create eight collections a year. One can argue it’s such an unhealthy pressure but this is the same pressure that a lot of athletes and artists are also dealing with. It's also the psychological part of running a marathon—being in it for longevity. There will be ups and downs but you can't give everything in the first couple of kilometers because then you will burn out. The same for creativity. No one else is going to help you remain and stay. The book speaks on how you can train to be 1% better every day. And if you become 1% better at what you do every day then you're 365% better than the year before [sic]. It's always a process.

NR

Every magazine you have started has had a predetermined start and end point. You published your youth magazine Recens for 5 years then promptly stepped down at the age of 18 because becoming an adult meant you were no longer fit to represent the youth. Wallet was a 10 issue run that aimed to challenge and critique the fashion industry whose duration was based upon 10 themes of comprehensive critique of the fashion spectrum.

What has informed you to operate in this way?

EO

In my publishing projects, duration has always been a very important element alongside speed and time. I ran hurdles when I was younger and I always looked up to the athletes who always ended their careers on top. For me, there's something really powerful about the idea of ending on top versus ending with an injury. It’s about knowing when to stop, pause or quit.

Time and duration plays into the idea of creating a myth33 or cultural spectacle. I think that the moment you stop is just as important or perhaps even more important than the moment you begin. There are a lot of people in this industry that should be more aware of their position, outdatedness and their relevance. I don’t mean that in a superficial way. For example, , who's been at Vogue for all these years, maybe it's time for her to step down and give space for someone else. We’re grateful for her contribution, but by holding on to her position she's jeopardizing the quality of her publication, the business model, her company finances, and ultimately she's jeopardizing the whole climate of printed culture. That's the risk when you hold a position just to hold it.

NR

Will the same critique exist of editors in 30 years? Will the hyper concentration of the self through the internet and social media breed another generation of power holders?

EO

I think that it's always healthy to have this sort of circulation of talent and a circulation of voices. It's of course also possible to renew yourself as long as you're publishing something that's genuine and feels in touch with your intuition and what you want to see in the world. The older generation is incredibly fearful of the new generation because we’re, I guess, so ‘new’ and ‘different’ and they don’t fully understand us. Misunderstanding can lead to horrible things. I think that power hungry people are oftentimes incredibly insecure but there’s also a very human element to this without going too deep. I was thinking about it today when I was at the roundabout and this person came really slow from the left side and I, you know, have better acceleration on my car so I passed him and felt this little sense of power...

We're also living in a time where, because of the internet, you can claim the space that you feel you should have in this world. This idea of myth making has always been there, and its principle is the same, but now we have different tools and different techniques of creating them. The same goes with your own persona, you can create something that's real or fake and it doesn't really matter. Social media is just a creation of your own universe and what doesn’t fit you let go. I think a lot of artists are dealing with these subjects right now as well. You know, the idea of identity and the self and perceived narcissism. It’s incredibly superficial at times and unhealthy and arrogant. But at the end of the day myth making is all you have as a person. You're in control of your own narrative by understanding who you're put in context with.

NR

Have you become more aware of your narrative?

EO

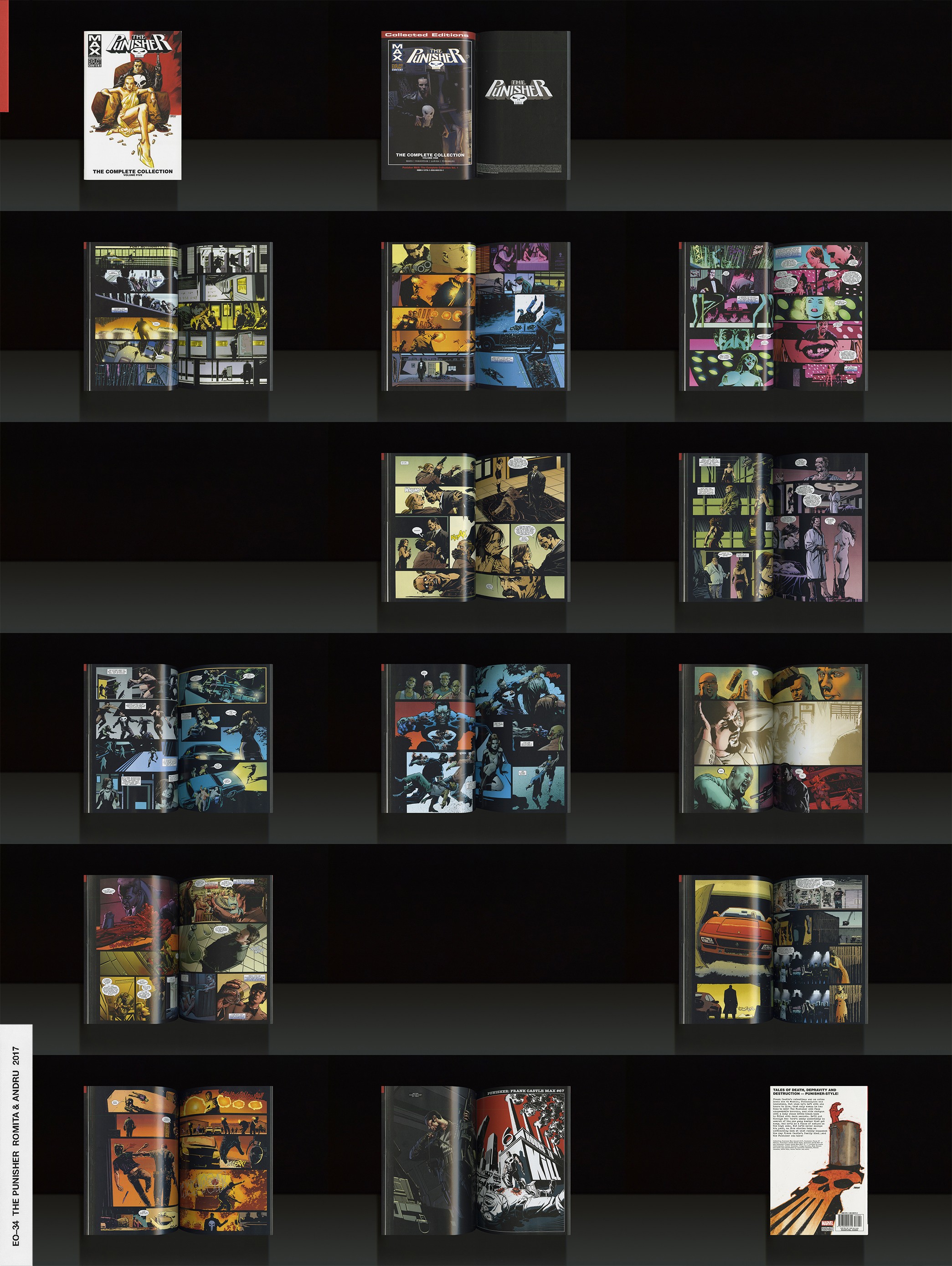

I’ve also been really obsessed with the Punisher34. I bought it right when I had my surgery and was like, on opioids looking through it and became super fascinated. There are all these chapters in the Punisher where ultimately the characters become hyper aware of this whole narrative in its totality. It gets meta. Some of these heroes like the Punisher are so similar to the character has been and is currently playing. Whether it’s or Kanye or any other players that are in this matrix right now, I think that they're all making these ‘radical’ points and performances because they’re aware of their influence. Changing their names, not changing their names, wearing a mask, not being super visible. They give and take, push and pull—it's part of something that's so much bigger.

I think it's important to not be too afraid of the commercial and to not shy away from visibility. And that's also why I think that in my trajectory, now, if I'm gonna continue to publish, I wanna try to do something that is more visible and less niche—something that has a wider point of departure. If you really want to make a big change, you need to get in there and actually do the change from the inside and sort of implode, rather than being bitter on the sideline. You need to get in there. So that's what I'm trying to do now.

The other day I was walking in the corridors of the and ran into this designer who also teaches there. You know, a very low scale, academic designer who has been practicing in Norway for the longest time, kind of a legend on the Norwegian scene. And they were so offended. They were like, “You are really just going at it, you're really selling out.” And I felt called out, you know? I feel like I'm owning it, or stepping carefully, but they were really offended.

NR

Why?

EO

For them, I think it was just the optics of me or my work being more public, scaling up, taking up more space. The fact that I’m working with bigger brands and gaining more visibility—things that I’m not shying away from that I used to shy away from. I really feel that this has happened genuinely, organically, and over time, intentionally. I think there’s a big misconception that people who are not close to me think that there’s this machinery behind me, agents pushing some sort of commercial agenda. But the reality is that what I have done, I have done on my own, I have never worked with agents, I have raised money for all the projects I have done myself. I feel very lucky to have an incredible team, and a strong support system consisting of a few very real people around me.

Ultimately, instead of being judgemental, I think it’s crucial to be generous with oneself and other people, and allow change to happen. Because people do change over time, times are changing, I’m maturing too. Bigger platform means bigger play, if you handle it correctly. The same money is going to be in circulation, and so you might as well be the one to take the money out of the system and do with it what you feel is for the better.